IT WAS ONE of those lousy late-fall New York evenings, cold and dark and sort of half raining and half sleeting. I walked out of my office and slipped on a patch of ice. It wasn’t much of a slip. I just twisted my left hip, then caught my balance. I went on my way.

The next morning, my hip hurt. I’ve had my share of sports injuries over the years, and it felt like that—a torn ligament, maybe. Then a few weeks went by and then another few weeks, and it still hurt. I went to see my orthopedist. He took some X-rays but didn’t see anything wrong.

My hip kept hurting, but I was too busy to see a doctor. I was 38, at my dream job, and the first-time father of a 7-month-old baby girl. A sore hip just didn’t seem that important. By the following November, though, my hip hurt all the time, and my doctor sent me for an MRI. A few days later, I went to his office to discuss the results. He closed the door, sat directly across from me, and fixed me with a professional gaze.

“I’ve got the results of your MRI,” he said. “There is a lesion on your hip.”

“A lesion?” I said. “You mean a tumor?”

“Yes,” he said.

And with that single syllable, I had cancer.

At the time I was diagnosed with what turned out to be an incurable form of blood cancer called multiple myeloma, I was told I had 18 months to live. Thanks to revolutionary new treatments for my illness that have been developed since then, that was more than 20 years ago. In the intervening years, I have been in and out of remission many times, but in each case, my doctors have managed to knock back my disease. It is not a stretch to say I am a medical miracle.

People ask me: What’s it like to live with an incurable illness for so long? The answer is, cancer has radically transformed every aspect of my existence—my physical health, my mental health, my marriage, my career, and more. But one of the most daunting challenges of living with a chronic illness, it turns out, is a mental hurdle: learning to cope with uncertainty. What’s it like to live with the knowledge not just that your disease might come back, but that it will come back, only you don’t know when? What’s it like to live your life in a state of perpetual uncertainty?

In researching my new book, An Exercise in Uncertainty, I spoke to a number of experts on the subject. (I’ve also learned more than my share about the topic through personal experience.) Whether you’re facing the uncertainty of a serious illness or just the anxieties of everyday life, here’s what you need to know to cope more effectively.

Waiting is worse than knowing

Catherine Sanderson, PhD, is a psychology professor at Amherst College who has studied uncertainty. To illustrate just how difficult it is to deal with it, she cites research showing that people who have a 50 percent chance of receiving an electric shock feel more stress than those who have a 100 percent chance of receiving a shock. “People are basically saying the anticipation of pain feels worse than the pain itself,” she says.

Another psychology professor, Kate Sweeny, PhD, at the University of California, Riverside, researches so-called high-stakes waiting periods—from law school students awaiting bar exam scores to women waiting for breast biopsy results—and how people respond to them. In one study Sweeny led, 50 law students who were preparing for the California bar exam answered questionnaires at 10 separate points in time. Among the study’s conclusions: “You worry a lot at the beginning, sort of forget about it in the middle, then worry a lot again at the end. It’s a U-shaped curve.”

Sweeny also found that optimists tended to report lower levels of anxiety and rumination. But her most notable conclusion was that even when the students received bad news, they were relieved to get it. “If they failed, they didn’t feel good,” she says. “But that anxiety just went away. The waiting,” she adds, “really is the hardest part.”

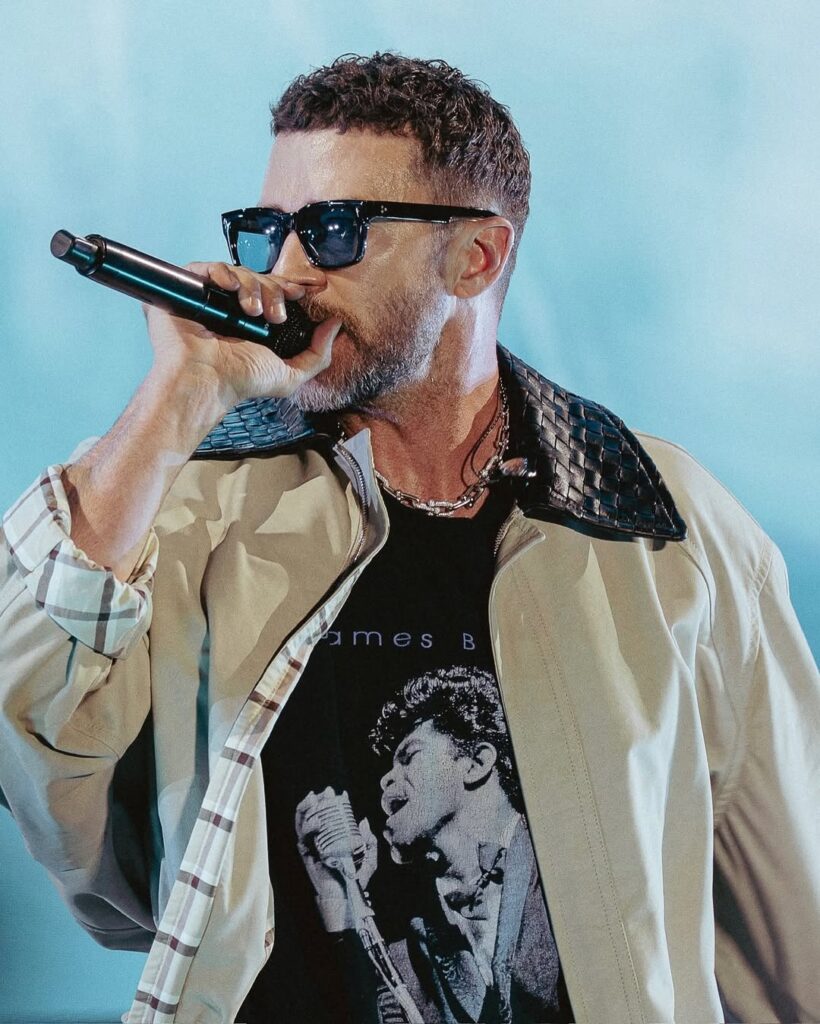

Gluck on a fishing trip in Alaska

Find a flow

In 2019, Sweeny and fellow researchers investigated whether “flow,” or being fully absorbed in an activity, helped people in three situations that typically induce anxiety. Participating in flow-inducing activities, they found, may boost people’s sense of well-being during a period of uncertainty and make the waiting a little easier.

Even during the pandemic, according to a paper Sweeny coauthored, people in a lengthy quarantine who reported higher-than-average flow experiences were no worse off in terms of overall wellness than people who had not yet quarantined. Engaging in deeply absorbing activities like running, painting, and gardening seemed to protect against the potentially harmful effects of quarantine.

In addition to flow activities, simpler diversions can also help distract people from negative thoughts, adds Sanderson. She cites a study in which researchers examined people’s reactions to a major earthquake near San Francisco. Those who reported distracting themselves by simply doing something fun with friends or going to a favorite place to take their mind off the event had fewer symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder than people who ruminated about the event.

Practice predemption

Exerting control, however you can, seems to give people some relief. Participants in Sweeny’s studies who were waiting for health results reported doing things like getting more familiar with their insurance policy, researching the best doctor they could see, and investigating what clinical trials were available, even before they received a diagnosis. “All in all, doing something is better than doing nothing,” Sweeny says.

It can also be helpful to look for silver linings in bad news before it actually arrives. Sweeny calls that preemptive benefit finding, or “predemption.” In one study, Sweeny asked people undergoing a breast biopsy, “Is there any good you can imagine that might come out of it if you find out you have breast cancer?”

“I thought maybe it would be insulting to even ask, but roughly three-quarters of the participants said, ‘Absolutely. I would appreciate my family more. I’d be a role model for my daughters. I’d get healthier.’ That sort of thing. Our evidence shows it helps people cope if they’ve already thought that through.”

Lean on others

Several years ago, Sanderson’s husband lost his job. It was a position he had held for more than 20 years, and he was let go suddenly and unfairly, she says. “We were definitely facing uncertainty.” At first, Sanderson says, she and her husband were reluctant to share what had happened with anyone except a few family members and close friends. They felt isolated and alone. But when they eventually started telling more people about it, they felt “flooded with love and support,” Sanderson says. In some ways, they “never felt more loved.”

“In psychology, we talk about two different kinds of support: problem-focused and emotional,” Sanderson tells me. “The first is ‘Oh, you have cancer? I know a great doctor.’ The second is ‘I’m sorry. I understand. I know you’re scared and worried, and I’m here for you.’ ” When someone is facing uncertainty, Sanderson says, practical support can be helpful, but basic sympathy and compassion can be every bit as powerful, if not more so.

The author with his wife, Didi, and their children, A.J. and Oscar, on a family trip to Spain

Control what you can control

I wasn’t aware of Kate Sweeny or Catherine Sanderson in the days, months, and years following my diagnosis, but it turns out my experience of coping with uncertainty has been almost eerily consistent with their findings. Waiting is more difficult for me at the beginning and end of a waiting period. When I get bad news, it is better, in some ways, than not knowing; at least it relieves the torture of waiting. Bracing for the worst ahead of time helps me accept upsetting information when it does come, as do participating in flow activities (fly-fishing is particularly helpful for me), distracting myself, and looking for silver linings. Any support I receive from loved ones, overt or perceived, practical or emotional, is a balm.

Still, nothing I have done has ultimately made my fears go away. Living with an incurable disease, I have found, is basically like waiting for a bar exam or biopsy result forever. The irony is that a heightened awareness of death can teach us how to live. You do what you can to make yourself happy—pursue a beloved hobby, spend time with family and friends, go to the gym—and hope for the best. Controlling what you can control and accepting what you can’t may not be the secret to human happiness, but it’s probably as close as we’re going to get.

This story is adapted from the book An Exercise in Uncertainty: A Memoir of Illness and Hope, by Jonathan Gluck and appears in the May/June 2025 issue of Men’s Health.

This article originally appeared on Men’s Health US.

Related:

How an Aussie entrepreneur turned cancer into a catalyst

Life reimagined: how I embraced new beginnings after prostate cancer