They say clothes make the man. They also reveal your deepest desires, motivations, fears, hopes and aspirations. Find out why what you wear could be the key to bridging the gap between who you are and who you want to be.

By a rough count, we are living in tracksuit pants’ third age. Lower-body athletic apparel has metamorphosised from highly functional, to strictly casual, to casually functional. Its latest incarnation is courtesy of the pandemic-driven Zoom boom of the past year. For me as a journalist they have been an essential component of the uniform I wear to conduct interviews, my interlocutors unaware that while I may be presenting in a neatly-ironed shirt, below the waist, it’s party time.

At least it was until today, when I find myself talking to Anabel Maldonado, a brown-jumper wearing, refreshingly forthright fashion psychologist at PSYKHE in London. Maldonado, who has a background in clinical psychology and fashion journalism, is in the process of casting her critical eye over my outfit – red, white and grey check shirt over a white Michael Jordan T-shirt – to give me an ad-hoc assessment of what my outfit says about my personality. It’s like being sartorially x-rayed.

“Stand up,” she instructs me. I try not to hesitate, feeling self-conscious about my well-worn khaki track pants lurking down below. I look at Maldonado’s face for signs of judgment but detect nothing. “Okay, sit down,” she says, before beginning to break down my outfit in relation to the big five personality traits: openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism and extroversion.

“I would say that you’re moderately high on openness in the sense that you’ve put something together that the average person might not necessarily pair together, but it’s also not so crazy,” she says, as I nod approvingly. “It just falls in that nice creative space. I’d say you’re moderately conscientious. You have a laid back, fun side, but you can get things done.”

So far, so f*cking great, from my perspective. “Agreeableness, moderate to high,” Maldonado adds. “You’re a nice guy. If someone’s debating at dinner over something controversial, you’re not going to get involved. And then neuroticism, I’d say moderate. Again, with the colour and the print, you seem to be a happy person.”

I should have stopped Maldonado’s glowing assessment there. But she continues. “I would say you rate pretty high on extroversion because you have the print, you have colour and you’ve got a conversation piece with your T-shirt.”

This is where things get a little complicated. No one who’s met me has ever called me an extrovert before. I’m reserved, at least until I have three beers under my belt. Or at least I thought I was. Are my clothes revealing a side of me that I’ve never really considered before? The fact is, as subdued as I might be in most social situations, I also have an exhibitionist streak. I shrink in the spotlight yet want to be noticed. Maybe, my clothes have been shouting this out all along?

It’s certainly possible. As I’m beginning to discover, your clothes reveal more about you than you’ve probably ever considered or would care to admit – your hopes, your dreams, your desires, even your fears. “From a psychological perspective, our clothing is a representation of our identity,” says Dr Carolyn Mair, author of The Psychology of Fashion and founder of the world’s first fashion psychology degree program at the London College of Fashion and the website psychology.fashion. “Clothing says who we are to other people, or rather, who we want to be.”

There’s clearly a lot at stake, with even seemingly innocuous sartorial choices helping create an impression that others will assess, evaluate and make judgments about in a matter of milliseconds. Mostly you rely on instinct to pull off the incredibly complex, staggeringly nuanced act known as getting dressed. You know, at a gut level, if a garment suits you. “When looking at clothes, the subconscious brain is saying this aesthetic and the qualities that it emits are in alignment with the values you have and the story that you carry around, as well as your psychological needs,” says Maldonado. And if a garment feel off, she says, it’s for the same reasons. “It’s at odds with who you are, who you want to be and how you feel.” It’s why the one pair of polka-dot socks in a Target five-pack never makes it out of my drawers.

So, while most of us approach the act of dressing intuitively aided and, indeed, abetted by prevailing trends and the machinations of the fashion industry, we’re usually doing so without much introspection, never fully contemplating that man in the mirror. The truth is, though, having more awareness of why you dress the way you do, understanding some of the psychological motivations behind your dress choices and harnessing the intrinsic and culturally embedded power of clothes to elevate confidence and performance, could help you gain a better understanding of who you are and what you want out of life. It might even be the Trojan (clothes) horse you need to achieve that vision.

BEING LIKE MIKE

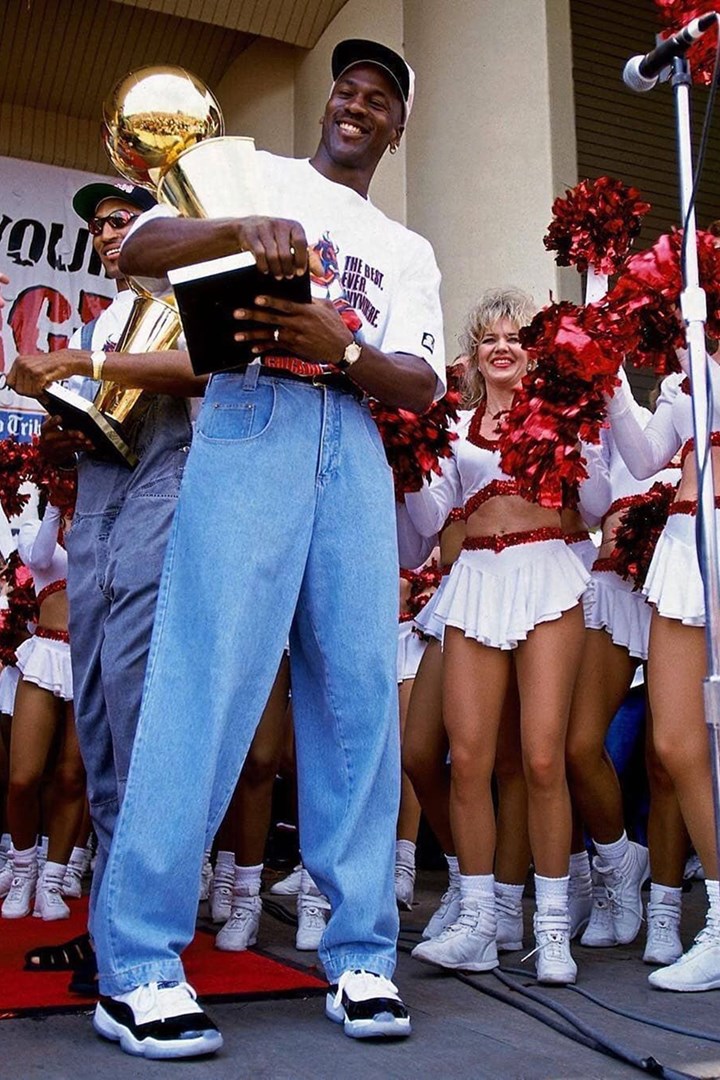

You wouldn’t know it now but Michael Jordan – the guy on my T-shirt – was considered one of the best-dressed men of the 1990s. Jordan led the trend among NBA players of arriving at games in designer suits. He even helped make baldness cool. But something strange happened to Jordan in retirement: he ceased to be fashionable, a fact best illustrated – and frequently memed – by the size of his trousers. While the general trend in suiting in the last two decades has been for a tighter fit, MJ’s remained resolutely baggy. The same with his jeans. In last year’s award-winning documentary, The Last Dance, his jeans could have provided shelter for the homeless. So, what happened?

Most likely, no longer being in the public eye, Jordan has ceased to care. As a dad and older man, perhaps he no longer feels pressure to keep up. Always a fierce competitor on the court, perhaps in retirement the fire has gone out, he no longer feels he has anything to prove – why would you when millions around the world wear your shoes and, guys like me, your T-shirts?

I thought of Jordan (as I often do) recently, while putting on a suit I planned to wear to a wedding. The trouser length was simply too long, causing them to bunch up at the bottom. I felt a tug of angst in my stomach. I can’t wear this, I thought. “Get them taken up,” my wife said simply. I did as she suggested, so that afterwards the trousers finished at the top of my brown brogues. I instantly felt transformed. The suit felt right. I couldn’t help reflecting, though, that unlike Jordan, perhaps I still have something to prove.

I also wondered what else my desired trouser length might say about me. Overly long pants just felt too daggy. But to go too short would have exposed my skinny ankles and although this length, in combination with going sockless, has been trending the last few years, to me it feels too risky. If, as Maldonado argues, my preferred trouser length is in alignment with the way I see myself, you would have to conclude that I’m aggressively average. The bigger question is why I feel this way?

“Your dress sense embodies your identity and it also reflects a collective conscious,” says Maldonado. “That’s what trends are. Something happens and society shifts the collective consciousness and that obviously affects you as well. But not everyone responds to all trends. You might really love one trend that happens to align with who you are and your values and you might not like another.” Jordan clearly didn’t care for the shorter, tighter pants trend.

Your response to trends is what Dr Alice Payne, an associate professor in fashion at the Queensland University of Technology’s School of Design, calls your level of attunement. “Some people will be very attuned to those kinds of subtle signals they might send out,” she says. “They just value that more than others.”

Our clothing, Payne believes, positions us in our culture, time and place. “It’s a means that we use both to fit in and to stand out,” she says. “It’s this kind of dance between being an individual yet being part of your group.”

Naturally, context is a crucial factor in the clothes you decide to wear. There is a performative aspect to dressing in public that draws more heavily on aesthetic factors, while at home functional considerations come to the fore. But clothing and fashion are never static, says Payne. What’s considered functional today can become fashionable tomorrow – think combat jackets or firefighter uniforms turning heads at high-end fashion shows.

At the same time, broader societal trends can often influence fashion. The pandemic has led to an explosion in leisurewear, while before that climate-change activism saw ‘the protest look’ show up on global runways, says Payne. “There’s 100 per cent a connection between what goes on bigger picture and how that’s expressed in fashion,” she says.

And those overarching trends still affect how you dress in private because even then, you need still need alignment, reckons Maldonado. “It’s not the same as if you’re at a party and you’re wearing the wrong thing, but you still feel icky, wrong, you can become irritable,” she says.

The fact is, clothing we feel comfortable or even confident in offers us intrinsic validation and that, in turn, can influence our behaviour. In a study published in Evolutionary Psychology, women wearing red were rated as more attractive than those wearing green, yellow or white in a series of photos. This wasn’t hugely surprising, says Mair. A large body of research has shown red is associated with attraction, among other things – more on that later. The researchers then showed a different group of participants the same photos in monochrome, so they couldn’t distinguish between the colours. Even so, the participants still said the women wearing red were more attractive than the others. Why? The researchers believe it was because the red clothing had influenced the wearers to the extent that they believed they were more attractive.

This sartorial placebo effect extends beyond attractiveness, to characteristics such as the confidence and conscientiousness you might feel when you put on a suit for a job interview, for example. “When you put on a suit, you feel more put together, you’re going to act more put together and you’re going to speak with more authority,” says Maldonado. “So, you feel those qualities and you embody them. And then you come across that way.”

Your clothing can even affect your performance on cognitive-based tests, a phenomenon known as enclothed cognition. A well-documented study by researchers at Northwestern University found participants who believed they were wearing a white doctor’s coat performed significantly better on tests that measured attention span and attention to detail, compared to those who believed they were wearing a painter’s coat.

The key here, says Mair, is the strength of the association you have with those clothes. “If someone associates a white lab coat with a chemist working in a pharmacy, or a technician then it doesn’t translate in the same way,” she says. “It’s about the belief that the wearer has in the sociocultural associations of those clothes.”

The power of belief extends to all aspects of an outfit, even those garments no one sees, like underwear. “Nice underwear makes you feel good,” says Mair. “It’s about self-value, and when we value ourselves, it boosts our self-esteem.” Which is why having a ‘lucky pair’ of boxers or socks is not an entirely futile endeavour. If you feel comfortable and validated by them, it will come across. As George Costanza once said, “It’s not a lie, if you believe it”.

RED ALERT

I once attended a high school football game wearing a red windcheater over a red polo shirt, tracksuit pants with red stripes, red sneakers and red socks. Our school’s colours, incidentally, were blue, purple and yellow. I hadn’t even noticed the extent of my commitment to the colour until a girl from my class exclaimed, “Ben . . . red!” At which point, my cheeks flushed red as I blushed, thus completing the look.

Block red clothing continued to be a staple of my wardrobe through university and into my twenties. Now though, as a more mature adult, I shy away from the colour. It feels too flashy, too bold. These days I lean toward earthier tones, or navy blue. I put it to Mair that my youthful preference for red perhaps reflected an unconscious yearning for attention, a way to broadcast my ambitions or to mask my insecurities.

“I think children often like bright colours and red would make you stand out,” says Mair. “There is a physiological association with red in the brain that fires us up. It’s not just psychological, it’s actually physiological. We’re excited when we see red. That was something in your personality. By wearing red, you might have got more attention. You potentially got the results you wanted.”

Numerous studies have found sporting teams that wear red are more likely to triumph. A study published in Nature that analysed results in combat sports in the 2004 Olympics found “a consistent and statistically significant pattern in which contestants wearing red win more fights”. Another study, published in Psychological Science, found competitors who wear red have higher levels of testosterone.

The colour also communicates sexual attraction, says Mair, who cites research that found waitresses wearing red will get more tips, while men dating a woman wearing red will spend more on her.

Sexual attraction is obviously a huge factor in clothing, as it is in many areas of life. A recent study at the University of Michigan found men who wear large logos – in this case Ralph Lauren Polo – were regarded by study participants as wanting to pursue short term relationships, while those wearing more subtle logos were viewed as more likely to be interested in longer term relationships. The study’s author, evolutionary psychologist Dr Daniel Kruger, categorised the two groups as cads and dads. “We were speculating that logo size would relate to the way men display resources,” says Kruger, as I self-consciously reflect on the size of my rather enormous Jordan logo. “Some men may use their resources more for advertising, sort of flashy cash, that’s more aligned with mating effort than it is with the resources they’re eventually going to invest on offspring. It’s not going towards their children’s college education fund.”

Logo size could be deployed strategically depending on social context, Kruger adds. “Mating effort is both trying to attract partners but also competing with other males,” says Kruger. In that sense, a larger logo expresses dominance and power to intimidate competition, he says. Smaller logos, meanwhile, were regarded as better choices for social contexts where you want to appear reliable and trustworthy, like meeting a girlfriend’s parents.

More broadly, Kruger believes clothes are symbols of wealth and status. Keeping up with trends, he says, is driven by a desire to maintain your position in society. “From an evolutionary perspective it’s a sign of our status and we’re motivated to maintain our status.”

But base motivations such as attraction, dominance and status aren’t the only things our clothes communicate. The amount of energy you invest in what you wear can also be a bellwether of your mental health. “There’s a huge majority of people who have clinical depression that tend not to bother about their appearance or their self-care whatsoever,” says Mair. “Clothing falls so far down on their agenda. The more we care about ourselves, the better mental health we usually have.”

What you wear can also reflect less extreme emotional states, such as feeling stressed or anxious, says Maldonado, citing New York Times’ photographer Bill Cunningham’s famous quote: “Fashion is the armour we wear to survive the reality of everyday life”. “In the research I’ve done, black is regarded as emotionally protective,” she says. “We also tend to wear oversized things like hoodies and thick sweaters that are heavier and can feel protective.”

If you’re feeling insecure, she adds, you may tend to overcompensate with bolder clothing. “If you’re feeling slighted or have a chip on your shoulder, you’ll look to make a lot of statements,” says Maldonado. “That’s often seen as a faux pas, but usually what’s underneath that is this feeling that you want to tell people, ‘I’m something, I’m here’.” It makes me wonder again if that was my motive in wearing so much red as a teenager. Too shy to vocalise my ambition and desperate need for respect, perhaps I relied on my clothes to do it for me.

TRIBAL MARKINGS

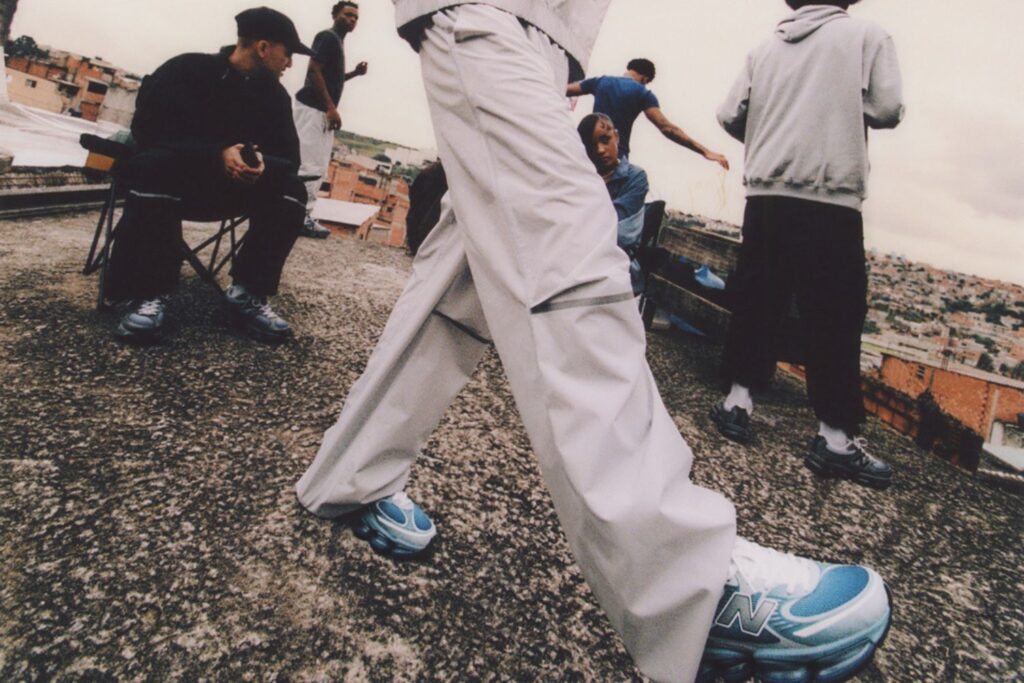

When Andersont Giovanni meets someone for the first time, he makes “foot contact before eye contact”. One of Australia’s leading sneaker collectors, Giovanni sees sneakers as more than just an item of clothing. “It’s a community, it’s a culture,” says the 23-year-old civil engineer, who lives in Sydney’s western suburbs.

Giovanni got into the sneaker game five years ago. The shoe that launched his obsession? The Yeezy Boost 350 Turtledove. At one point, he had over 200 pairs of shoes in his collection, which he’s now culled to 50 ‘Grails’ – “shoes that are extremely limited or have historical value”. The most he’s paid for a sneaker is $2000. The most he’s sold a shoe for? “I helped a friend sell a pair of Air Diors for $18,000.” Among his collection, only three pairs of shoes are ‘deadstock’ – box-fresh shoes you never wear. When it comes to dressing, he prefers to wear monochrome. “I’ve always tried to keep my clothing subtle so that my shoes can stand out,” he says. “I’m that type of person.”

For guys like Giovanni, his clothing distinguishes him, while also connecting him to his tribe. “If you’re a part of a subculture, the way you’re dressed identifies you with that group and they recognise you as part of that group and then you can interact with them freely,” says Mair. “It’s like a language and if you don’t speak it or you’re not fluent in it, you can miss the meaning. Fashion purposely binds us to some groups and distinguishes us from others.”

You may not be a committed sneakerhead or a punk or a goth or anything so defined. Heck, you might just be a daggy suburban dad. But on some level, however subtle, you belong to a fashion tribe. And while it may not be distinct, your tribe will inform what you wear. “You’re editing as you’re observing people in your circle, whether you know it or not and we reflect that in our choices, too,” says Virginia van Heythuysen, one of Australia’s leading stylists and fashion director at AFR Magazine.

What’s more, your tribes change as you move through life – many former punks are now suburban dads. Collectively, these tribes are part of and contribute to, what is known as ‘culture’, a vast resource from which styles and trends are interpreted, synthesised, reinvented and ultimately commodified by a gargantuan, dynamic hive-mind: the fashion industry. “In contemporary Western culture fashion is this kind of forced frogmarch of change in which the industry has embraced the desire for individuality, the desire for newness, the desire to differentiate oneself in class and in wealth and status,” says Payne. “Clothing companies have adopted that and then built this entire system around what is an innate human expression of culture that evolves and changes.”

And, whether you pay much attention to them or not, reverberations within that industry trickle all the way down to your own musty wardrobe and affect your attitude to the clothes in it. My Jordan T-shirt was once an A1 item for me. It aligned with my personal tastes, reflected the image of myself I wished to project to the world and identified me as belonging to a tribe – let’s call it the middle-aged-men-who-can’t-grow-up tribe. I reserved it for social occasions, like barbecues. Now? I wear it around the house, or under shirts in Zoom interviews, Jordan’s image my own Superman logo. “Our wardrobe is an ecosystem of clothing that we own,” says Payne. “Clothes have a life in one’s wardrobe and the value we place on them shifts and changes over time.”

The Jordan Tee has remained my favourite, my ‘Golden Boy’, to quote Jerry Seinfeld, even as its status has evolved. The reason for that is both highly complicated and wonderfully simple. “Those clothes still speak to the same human impulse,” says Payne. “It’s about feeling right.”