Even with an infusion of some of the best marketing available – a turn on an episode in the sixth season of Queer Eye – the promotional wheel never stops a-spinning for a nascent gym. So it is at Austin’s Liberation Barbell Club on a sweltering Saturday in mid-July, as Laurie Porsch and Tyler Jacob Villarreal tend to the club’s Instagram. Porsch, 35, is the owner of Liberation, which she founded just before the dawn of the COVID era. Villarreal, 23, is a trainer at the club who has also taken on social-media duties.

Porsch is small, strong and quick, with hot-pink nails and a cloud of dark, curly hair. Fuelled by “an unhealthy number” of Red Bulls, she has lifted off from the standing desk in the front office and is now darting around the gym, demonstrating for Villarreal how to properly photograph Liberation’s clients for Instagram. The day’s visitors are a distillation of Austin-core: they are tattoo prone and friendly, and everyone looks like they could paddleboard for 40 kays. Nobody seems self-conscious when Porsch squats down and begins taking pictures of them in front of the giant wall of pride flags that backdrops the heavy-duty strength-training equipment. “Show me how it’s done, Laurie,” Villarreal says a little sardonically, following her around the gym.

“You’re overthinking it – it can be super simple,” Porsch says, ignoring Villarreal’s Gen Z cynicism and hunching down, phone up, behind a client who is easily slicing through the air on a rowing machine while chatting with a friend.

But Villarreal’s task is not so straightforward: how do you capture a gym’s vibe? Even if you’re really gym savvy, walking into a weight room for the first time can conjure a “new kid in the lunchroom” anxiety, compounded, for many, by the fact that serious lifting equipment can signal an intimidatingly macho, cishet scene.

Most commercial gyms, such as Gold’s Gym and Planet Fitness, have sought to mitigate that intimidation and to create inclusivity: a safe and inviting spaces for everyone –regardless of disability, ethnicity, fitness level, gender identity, income, race and beyond – through marketing campaigns, nondiscrimination policies and more-tactile investments, such as wheelchair-friendly equipment. But these sprawling, franchised communities don’t always instil that inclusive attitude in their clientele and staff the way a local gym, like Liberation or Seattle’s Rain City Fit, strives to do. In 2015, a Michigan pest sued Planet Fitness for revoking her membership after she complained about sharing a locker room with a trans woman, and in 2018, a trans woman in California sued a Crunch Fitness after she was denied the use of the women’s locker room. The gravity of the “fitness for everyone” movement is most potently felt in Liberation-sized gyms.

Just look to the flags. The north wall of Liberation looks like the pride United Nations: a genderqueer pride flag is flanked by a bisexual pride flag and a trans pride flag, and the procession continues across the wall. “Most people will come in here and go, ‘Well, I know the rainbow one, but… I think that’s a trans one? What are these other ones?’ ” says Ean Ashford, 38, a Liberation employee turned client who just strolled through the door. “It’s endless – you can be whatever you want.”

An Italian flag hangs on an adjacent wall, a Washington, D. C., flag on another. “For anybody else who doesn’t feel at home, we’ve got some country flags,” Ashford says, laughing. “Military, we got you covered, too. Chicago, we got you covered. Texas, we’re good. Whew!”

Porsch has a background in martial arts and the U.S. Marine Corps, so she was used to being the only woman in male-dominated gyms. “People will be like, ‘Oh my God, but the guys there are the nicest,’ ” she says of those spaces. “Well, of course they’re the nicest, but there’s still a barrier to entry.” Porsch wanted Liberation’s inclusivity to be immediately inviting for all – she says one client used to arrive in a MAGA hat – but its target demographic is those who traditionally might not see themselves represented in strength sports like Olympic lifting, powerlifting and strongman.

“It started with a friend of mine who happens to be transmasc, and he said something about how he was really dehydrated at work because he didn’t want to use the restroom,” Porsch says. She asked him where else he didn’t feel comfortable going into the restroom, and he told her the gym could be stressful. “In my head, I was like, I can make it where you’re not stressed at the gym.”

Porsch wondered what would happen if she combined the best equipment she could source with a very intentional design, with elements that would appeal to people who may have felt disenfranchised by gyms in the past. Gyms that made clients choose between a men’s and women’s locker room, for instance, or whose code of conduct did not address hateful language.

Client Ryli Webster, 40, says that when he and his partner joined Liberation, they had previously been members of a gym that aspired to be inclusive and that they liked. But even there, “a lot of the ways that they talk about the standards of athleticism and fitness were very binary in terms of gender,” he explains. “It’s a typical CrossFit type of gym: they have bars that are allocated for women and bars that are allocated for men and certain weight prescriptions that are allocated for each.” Porsch wanted to nullify all those moments of uncertainty in the gym.

Besides the flags, Liberation would have bright blue walls and orange accents, and it would be well lit. On the website, each trainer and staffer would be introduced as a smiling cartoon, with their pronouns listed beneath their name.

The restrooms would be gender neutral and single stall. (In one, a stick-on banner atop the mirror reads you’re doing amazing, sweetie – an encouraging post-pee message for all.) Ten “elements of dignity”, from conflict-resolution researcher Donna Hicks, would hang near the entrance, right over the gym’s code of conduct, which reminds Liberation-goers that “invalidation of individual rights makes people feel like shit” and to rerack all weights and barbells, please.

The gym’s aesthetics were important. But the most critical element of all would be the people.

The Liberation Barbell Team

Laurie Porsch: owner

Workout anthem: “H B I C” by Gin Wigmore

“There’s tonnes of qualified trainers,” Porsch says when asked how she selected her staff of seven. In addition to trainers who deal in sound science, she looks for people who are “professional but not cold”. No trainer has the lived experience of every community reflected in the flags on the wall, but Porsch does require trainers to be open to the identities around them and familiar with the vocabulary of inclusivity.

“Really, the way you train someone who is, say, trans nonbinary is no different than how you should train anybody else,” she says. Every client has individual needs, anxieties, injuries and goals, all of which should be approached thoughtfully. “If everybody came in with the same recognition of dignity,” Porsch says, “everything would work itself out.”

Tyler Jacob Villarreal: coach

Coaching icon: John Berardi, PT

Villarreal was raised in a small conservative town in the Rio Grande Valley in south Texas. “Anything outside the cishet experience was ‘weird’, ” says the trainer, who is currently exploring his identity. But in 2020, he fell into a productive spiral over the country’s terminal injustices. He now has an Instagram account, @theleftistlifter, that seeks to “bridge the gap between Leftism & health and fitness”.

“Having people like Laurie, who create something like Liberation where people can come and feel safe and feel seen and feel loved and accepted for who they are… it’s a really cool thing,” Villarreal says.

Angel Flores: coach

Training icon: “My training is unique and specific to me and my identity. The only people I idolise are those who train beside me.”

Angel Flores found Liberation in August 2020 when she was looking for a coaching job. “It was a space that allowed me to completely experience the new things that I was experiencing, since I was also freshly transitioning at that time,” she says.

Liberation became a bastion for her. She used the gym as a sketch pad for new movements, a new body and new clothing. Then, in March 2021, Netflix called: Flores’s Liberation peers had nominated her for Queer Eye.

Now she does speaking engagements. Generally, people are surprised to learn there’s a queer gym in Austin. It’s an easy sell, though: “If I’m able to safely train in a space, then damn near anyone can,” Flores says.

Isaac Stehlik: Front desk staff

Frenemy exercise: Bulgarian split squats.

“Being a straight cis man, it doesn’t bother me going to commercial gyms or anything, but in the same sense, if I go to a commercial gym and take off my shirt, people are going to come up to me and be like, ‘Oh, you’re so this, you’re so that’,” says 22-year-old Isaac Stehlik, who is six-foot-four. “Usually it’s like a good thing . . . but sometimes you don’t want to be scrutinised by everybody. When you come here, people are just gonna do their thing and more or less ignore you, unless you want to talk to them, in which case they’re super friendly.”

Jazmín Reyes: head powerlifting coach

Best fitness advice: “Perform every movement with effort and intention, even your warm-ups. This will ultimately train your body to lift more efficiently and explosively.”

Jazmín reyes, 27, began training in Chicago; there, she says, powerlifting is a pretty niche community. “There’s like one or two powerlifting gyms, and there’s not a lot of women in the sport.”

Now she coaches a powerlifting group at 6am, comprising mostly people who are new to the sport.

“Being in the health space for a long time” – Reyes has done martial arts, gymnastics, swimming and boxing – “I’ve definitely seen the toxic parts. I’ve definitely been told, ‘Oh, don’t get too big’. ‘Don’t hurt your pretty little face.’ . . . I’m just like: I’m gonna keep doing this, and I’m gonna be good at it.”

Seven more spots where fitness is for everyone

1. Ironbound Boxing:

“Iron” Mike Steadman, former U. S. Marine Corps infantry officer, founded a free boxing program in Newark,

New Jersey, Ironbound Boxing, and serves as its CEO.

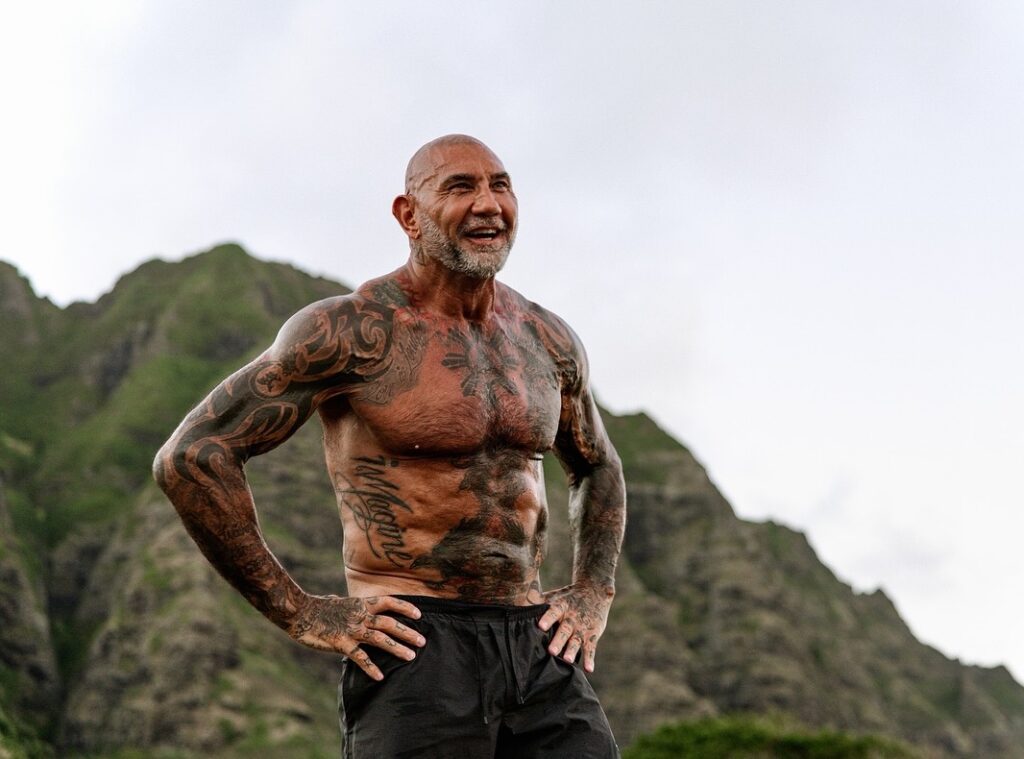

Finding a new purpose as a military veteran isn’t the most straightforward transition. For “Iron” Mike Steadman, 35, a former Marine infantry officer, his civilian purpose came from boxing. In 2017, two years after leaving the service and relocating to Newark, New Jersey, he started the nonprofit Ironbound Boxing, a free boxing program for kids from marginalised communities.

“Giving back was extremely important to me, especially being a Black male growing up in a single-parent home. I understand firsthand the challenges faced by young men and women of colour, and I didn’t want to just be remembered as an infantry officer,” says Steadman (above, left). Through boxing and the military, he’d transformed himself from an insecure kid into a college grad, a three-time national collegiate boxing champ, and a commissioned officer in charge of leading others.

Working as a residential housing director at St. Benedict’s Prep in Newark, Steadman founded a small boxing club but needed a gym in order to expand. After being given a space by the city, he raised money from veterans groups and others to get the gear necessary to open. All of the coaches are volunteers.

“Boxing has a violent stigma,” he says. “So you’re going into an urban environment where there’s already a certain level of aggression. And sometimes people in corporate America get confused about why we are teaching these kids how to box. But veterans understand old-school values, the principles of facing adversity head-on while building grit and resilience in the ring.”

Calling Ironbound a gym would be underselling it. Steadman describes boxing as a conduit to “capacity building”, teaching the intangibles – quick thinking, patience, timing – that are key for real-world success. Five years after Ironbound opened, Steadman isn’t satisfied, even though the program has awarded US$25,000 in educational scholarships and US$15,000 in microgrants to young entrepreneurs. Ironbound has trained 150 kids and sent teams to the USA Boxing Nationals. This year alone, it sent fully funded six boxers. – Clyde Gunter

2. Equally Fit

Mark Fleming, a trainer on the autism spectrum, embraces neurodiversity at his gym.

The fact that rates of obesity, diabetes and depression are all higher among those with autism spectrum disorder is the main reason trainer Mark Fleming, who was himself diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome at age 11, opened Equally Fit, a gym in Tampa for neuro-diverse people, in 2018. “Exercise not only improves your overall health, but especially your mental health,” he says. “Having an outlet where you’re exercising and gaining confidence and independence can be life changing.”

Fleming (below, left) often works with neurodiverse people who might be distracted by the loud music in a typical gym and who may need different motivation. The goal is to use functional training that incorporates strength and cardio as well as things that can help improve motor planning and social skills. Initially, he focuses on exercises that deliver obvious benefits (think balance moves) or feel good (think stretches).Fleming is also starting a fitness nonprofit called the Disability Fitness Foundation in order to reach as many people as possible. — Ben Court

3. The Adaptive Training Academy

Founded by Alec Zirkenbach, this nonprofit equips fitness pros with the expertise needed to train people with disabilities.

After his right leg was crushed between two ships while serving in the Navy in Somalia in 2009, Alec Zirkenbach spent almost a year rehabbing before deploying again. Zirkenbach (above, right) leaned into CrossFit to forge the fitness he needed to serve – he says the community spirit saved him – and just before leaving the Navy, he founded Fathom CrossFit in San Diego in 2012. The initial goal was to provide a space where wounded soldiers could train, but that quickly expanded to include all people with disabilities. “Fitness isn’t specifically aesthetics,” he says. “It’s not siloed [away from] your mental health – it’s all connected. Without community-based fitness and a supportive network, I wouldn’t exist today.”

Zirkenbach’s personal experience, as well as what he learned in talking with other veterans, athletes, trainers, doctors and therapists, led him to develop an adaptive training program for CrossFit and eventually to form the Adaptive Training Academy (ATA) in 2017. It provides fitness professionals with the skills they need to train those with physiological and cognitive impairments, whether that means adjusting exercises for amputees or creating programs for people in wheelchairs.

“One quarter of Americans have a disability, but when you walk into a gym, that’s not what you see,” he says. “In every fitness facility, there should be at least one trainer that has taken some [adaptive training] education, preferably ours.”

So far, 2700 trainers have graduated from ATA – with many more to come. The all-go Zirkenbach is also the accessibility and adaptive sport specialist for CrossFit and runs the CrossFit Games’ adaptive program, which now has eight categories. – B. C.

4. The Front Runners

This running club welcomes all people for group training, fun runs and more

The best fitness clubs deliver more than exercise. “When I came to New York, I didn’t know anybody. Now all of my friends are from Front Runners,” says Gilbert Gaona, president of Front Runners New York. “If I didn’t have this club, I would be lost.” Front Runners started in 1974 in San Francisco as a running club for gay and lesbian people, and it now has 100 clubs worldwide. New York’s was founded in 1979 and offers three fun runs and five coached workouts weekly. All adults are welcome. Group runs are divided by pace, and no one runs alone. Runners often ask head coach Mike Keohane how they can get faster, and he has three tenets: 1) Run hills once a week, whether it’s an up-and-down route or hill repeats. There’s no better way to strengthen your legs. 2) Run at high intensity once a week. If you’re breathing easy, push harder and try to maintain that faster pace while exerting the same energy. And 3) Be consistent and patient – your body needs time to adapt. – B. C.

5. Free to Move

Trainer AK Mackellar founded their own fitness platform to welcome beginners, the LGBTQ+ community and people with chronic pain and illness.

When a mountain-bike crash left AK MacKellar with a traumatic brain injury, the personal trainer reset their approach to fitness. “I was always an athlete, always going hard and pushing my limits,” says MacKellar, who lives in Vancouver. “After the crash, my body said slow down.” MacKellar realised that others like them might benefit from a gentler approach to fitness, embracing all body types and with an open mind to the gender spectrum. “Many people feel that they’ll be judged or looked at in some way. Free to Move is for all of them.” MacKellar founded Free to Move in 2020, offering virtual sessions, both live and on demand, plus movement challenges.

The approach resonated. Soon they had 130,000 followers on TikTok, with some reels, like a primer on motivation, garnering 500,000+ views. MacKellar wants to help clients reach their fitness goals, but the focus is long-term. “I often say, ‘Remember, this fitness journey could last 50 years or more. Take it slow’.” In a recent IG post, they wrote, “I’ve been strength training for 13 years . . . And my body looks pretty much the same.” But then they listed all the benefits: stronger core, hip pain reduced 90 per cent, improvement in managing mental-health flares, and increased energy. The takeaway: fitness should make you feel better. Recently, MacKellar has urged clients to do a 10-day “get outside” challenge. “The goal is to motivate people to move outdoors for 10 days, whether that’s doing a long trail run or walking around the block. It’s about doing what you can. Every little bit helps you feel better. ” – B. C.B. C.

6. Nubability Athletics

When he was 17, Sam Kuhnert recognised the need for sports camps for kids like him who are limb different.

You can’t, you’re not capable,you’re going to fail. That’s what Sam Kuhnert, who was born without a fully formed left hand, heard over and over growing up in the three-light town of Du Quoin, Illinois. But Kuhnert persevered, playing basketball and football and excelling as a baseball pitcher. At 17, he was invited to Camp No Limits, a workshop in Missouri for kids with limb loss or limb differences, and realised he could be a difference maker. Most of the children were missing one hand, and most said they played only soccer. “I felt like kids should try different sports, even if they fail,” he says. “I realised many kids are being held back and only pushed into these sports that their parents think they can play.”

With the help of his own parents, Kuhnert organised a sports camp in 2012 for 19 limb-different kids with seven coaches and mentors who looked like them. His mentality is that being limb different is not a disability, but it is a difference. He recalls a game of Wiffle ball at that first camp when Zoe, a four-year-old with no arms, came up to bat. “I was wondering, What’s she going to do? How can she be successful?’ Zoe said, ‘Give me the bat.’ ” He put it right under her chin. She hit the first pitch into the outfield, and Kuhnert says he’s never doubted a child’s ability since.

He created the hashtag #dontneed2 (whether it’s hands, arms or legs) to express that attitude and found that it helped grow the kids’ confidence. Every year, his NubAbility Athletics Foundation runs more camps for more kids – 13 in 10 states in 2022 – and about 70 per cent of participants attend on a scholarship. “We don’t ever want a child to feel like they’re gonna be held back out of finances,” says Kuhnert, who fundraises year-round for the program. What’s next? He hopes to take the camps global.

Kuhnert, 30, is pursuing his own fitness goals, too, aiming to bench-press 200kg by the time he turns 40. “It gets a little scary once you get more weight up there, but one thing about fitness that I’ve learned – and it goes back to living with limb difference – is if you beat yourself in your mind before you ever get under the weight, the weight’s a lot heavier. But if you have the confidence to go at it, knowing that you can achieve it, the weight gets lighter.” – B. C.

7. The Fitness Warriors

Ricky Martin started a free fitness class that now reaches 7000 people.

Ricky Martin, a trainer and community-outreach worker in Richmond, realised his people were suffering: he saw high rates of obesity and diabetes – “[We all had] family or friends who were dying” – and little structure to help folks begin a fitness journey. In 2014, he created a pilot program to instruct people how to teach a group fitness class. “The volunteers came from underserved communities, and they looked like people in those communities, and so they had a heart for it because they understood the urgency,” he says. Ten women showed up for the first session and learned to teach a class Martin developed with the American Council on Exercise. It requires no equipment and mixes calisthenics and core moves.

Then Sports Backers, a local nonprofit that encourages active living, teamed up with Martin to scale the program and give it a name: Fitness Warriors. It grew and grew; so far it’s offered as many as 60 free fitness classes weekly in the greater Richmond area. Martin says the challenge is that students in a class often have a diverse range of abilities, so instructors need to be able to adjust for, say, an elderly obese person as well as a fit young man recently released from jail. One of Martin’s favourite workouts is a 10-10-10 ladder of jumping jacks, sit-ups and push-ups, all moves that can be easily modified (on your knees for easier push-ups, clapping for harder). His personal record is 2 minutes, 43 seconds. He says the group typically does it in under seven minutes, with participants cheering one another on to finish.

During the pandemic, Fitness Warriors switched to virtual and outdoor classes and saw attendance drop from nearly 14,000 annual participants to 7000, but the numbers are going back up now.

As for the need for and benefits of the classes: data from 2021 reveals that 82 per cent of participants were overweight or obese and that 84 per cent improved their ability to do daily tasks, 56 per cent lost weight, 35 per cent reduced their medications and 90 per cent reported decreased stress.

Martin, now 66, says the program is strengthening the community in every way and hopes that other states can institute similar free fitness classes. “It’s not just the program that changes people; it’s the connections they make that change people.” – B. C.

This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of Men’s Health Australia.

Images: ARTURO OLMOS. Keith Brake Photography (NubAbility). Courtesy Sports Backers (Martin). Courtesy subjects (Future of Fitness).