It’s a Wednesday morning when I speak by phone with Mark Philippoussis, who it so happens is coming down from a surfing-induced high. The previous day he’d struck it lucky at his local beach of Jan Juc, southwest of Melbourne.

“It was getting to low tide and that spot is best in low tide,” he recalls. “It was one of my favourite breaks and super clean. Normally, there are 20 people vying for one take-off spot, but it was just me and another guy. My wife had gone for a walk with my daughter, and my son was at school, so I had nothing to rush back for. I was out there for two hours.”

We talk into the afternoon, and virtually irrespective of the topic – family, his new business venture, tennis, fitness, his recent plunge into military-style training – Philippoussis sounds uniformly enthused. He is either a singularly fulfilled and contented man or masterful at giving that impression.

On and off between 1995-2006, Philippoussis was among the world’s best and most compelling tennis players, peaking at a ranking of No. 8 in the first half of 1999. Handsome and burly, with the chest and shoulders of a rugby forward, the 196-centimetre gentle giant owned the sport’s biggest serve, which he backed up with a power-laden baseline game and penetrating volleys.

On his day he could dust anyone, but because he instinctively trod a fine line between boldness and recklessness, he could also fall backwards out of tournaments at the darndest times. He reached finals at the US Open (1998) and Wimbledon (2003) and won the decisive rubber in two Davis Cup finals (1999 and 2003), and yet the hard-headed rap on Philippoussis is that he didn’t quite fulfil his potential, that a frivolous lifestyle and questionable work ethic stymied an outsized talent.

These days, he’s sometimes spoken of in the same breath as Nick Kyrgios, but that comparison is unfair – to Philippoussis. Unlike Kyrgios, Philippoussis was prepared to lose without obscuring shortcomings behind a mask of indifference, and it’s hard to recall the older man ever being querulous, much less obnoxious, on court. He seemed sad at times, and strangely vulnerable for such a physically imposing man, but he never made you want to switch off the TV in disgust.

Philippoussis is on the line because the second series of SAS Australia, in which he appears, is soon to go to air. If you’ve seen the show, you’ll know that its resident taskmasters appear to revel in subjecting participants to all manner of hardship: hunger, cold, Room 101-type scenarios, humiliation. Why put yourself through it? “I felt like for too long I’d been too comfortable,” Philippoussis replies in an accent that is an Australian-American hybrid (up until 2019, he’d spent the previous 23 years based in the US). “I wanted to be pushed out of my comfort zone in an extreme way.”

Although he went on SAS expecting a physical ordeal, he underestimated the show’s psychological demands, he tells me. For many years he had thought of himself as exceptionally mentally strong, hardened to the point of impregnability by that decade spent in the

cauldron of pro tennis, as well as by the rough and tumble of life. “You’d imagine that in a

journey of 44 years, you’d know yourself pretty well,” he says. “You know what I mean? But it’s amazing that I learned so much more about myself.”

He seems to be setting the stage for an admission: that he’d discovered he wasn’t as tough as he thought he was. Instead, he goes the other way. There are two types of pain, he says: one, intense physical pain that doesn’t last; and two, “personal pain . . . shit happens, and that pain doesn’t end – you just learn to accept it and live it with it, day in and day out”. The pain he experienced on SAS, he says, was the first type: ephemeral; manageable. So, I ask, were you as stoic as you thought you were?

Yes, he says. “I honestly learnt that I’m even tougher than I thought I was. I don’t want that to sound arrogant in any way. I just want it to come from a good place.”

For him, Philippoussis explains, SAS was less a show than a test – a test from which he aimed to emerge “upgraded”.

Upgraded?

“Yeah, so I can be a better husband, a better father, a better friend, a better son, a better brother, a better listener, a better human being. Yeah, I wanted to come out upgraded. And I wasn’t disappointed.”

STRING THEORY

If you rose to No. 8 in the world at something but kept hearing, even in retirement, that you’d partially squandered your talent, do you reckon that might get to you? I ask Philippoussis whether he gave tennis his all.

There’s no sign the question bothers him. On the contrary, he says he can understand why people might have their doubts about how hard he worked. “But I’m very comfortable [addressing] this, because it’s simple.”

As a boy of Greek and Italian heritage growing up in Melbourne’s western suburbs, he says, he “ate, slept and breathed tennis” – and it was a good thing he did, he adds, because nothing less would have been enough. Preposterous, really, he says, in hindsight, the idea of aiming to make it on the absurdly competitive ATP Tour. “They say ignorance is bliss, and it honestly was for me and my father.”

When Philippoussis was about 20, doctors gave his cancer-stricken dad and coach, Nick, six months to live. And while Nick ended up pulling through, the son’s perspective on tennis had been realigned for good. “You look at things differently,” he says. “When you lose a match, you’re not so upset about it anymore.” But just because he had learned to keep defeats in perspective, it doesn’t follow he cut corners. “When it came to training, I woke up in the morning and I trained my arse off,” he says. “Don’t get me wrong, man: I trained my butt off. But as soon as my training was done, I also went and enjoyed myself, whether that was something I wasn’t supposed to do, like motorbike riding, or getting in my car and driving somewhere for the weekend or going snowboarding.”

Why?

“Because I lived life to the max and that was the same way I played tennis. Did I go for winners when maybe I shouldn’t have? Sure, but that’s the way I played. Someone would say to me, ‘Mark, you know, you can also win points when your opponent misses a shot’. I knew that, but it didn’t feel as good for me. Do you know what I mean? I had glimpses of greatness on the court. Matches of greatness. Even tournaments of greatness. But it wasn’t consistent greatness because to have that you need to eat, sleep and breathe tennis. There has to be nothing else for you. That’s the reality.”

He tells a story about spending two weeks in Los Angeles practising with a soon-to-retire Pete Sampras, who was a leading GOAT contender before Federer/Nadal/Djokovic rewrote history. Sampras was a phlegmatic athlete, but one morning he showed up at the courts abuzz. “Man, I couldn’t sleep last night I was so excited,” he told Philippoussis. “Yeah? What were you excited about?” “I’ve got this new string in my racquet!” Philippoussis was dumbfounded, before realising something. “Pete, that’s why you’re Pete Sampras and you have 14 grand slams,” he said. “Because when I can’t sleep at night, it’s not because of a new string.”

Another time, Philippoussis arrived at a tournament venue to play a night match and was surprised to find his compatriot, former world No.1 Lleyton Hewitt, kicking around in the dressing room. Hewitt, he knew, had played the first match of the day; he should have been long gone. “I’m like, What the fuck!” Philippoussis recalls. “I said, ‘What the fuck you doing here? Go home!’ But he was like, ‘Ah, nothin’, mate, just hangin’. See, he loved it. He still does. You can see it. He still eats, breathes, sleeps it. That’s just not me and it never was me.”

You could say that as a sportsman, Philippoussis lacked this or lacked that, but what you’d really be saying is that he was a little too normal, insufficiently descended into obsession. “But it doesn’t mean I was lazy,” he says. “I wasn’t lazy.”

Something else I’d like to know is whether Philippoussis carries any bitterness from his days on the tour, whether he’s still angry with certain people over certain incidents or comments. It’s not worth going into specifics, here or with Philippoussis, but he gets my drift. “Oh, God, let me say this,” he says. “I don’t carry anger about something that happened yesterday. Life’s too short.”

A QUIET PLACE

He keeps in good nick. At 92 kilograms, he’s five kilos lighter than he was in the 2003 Wimbledon final, where he had the honour of sorts of becoming Federer’s first victim in a grand slam decider. He’ll go occasionally to a commercial gym, he says, but his gym is really the outdoors, specifically the ocean. Surfing, he says, is his passion, his principal form of exercise – and his meditation. Six knee surgeries have turned him off running, but he briskly walks the steps of the Jan Juc cliffs two at a time in a weighted vest or backpack – up and down, up and down – and does mountains of push-ups and planks.

When it comes to fitness, his mantra is functional. He favours movements that will help him on the tennis court, because in a good year – a non-pandemic year, in other words – he’ll play up to 12 events around the world with his fellow titans of yesteryear. “Tennis still gives me joy,” he says. “I still play a game that I fell in love with as a kid, but without all the stress and politics that come with the main tour. I re-fell in love with tennis by playing the Champions Tour.”

At these events, he’ll face off against the likes of Tim Henman, Andre Agassi, Goran Ivanišević. Everyone still wants to win, he says, but afterwards the warhorses will bond over a drink or a meal. “And the beautiful thing is that the shield that you need to have when you’re on the main tour is down, and we talk about family, and we know each other’s kids’ names and what they’re up to. Everyone finally lets go. We’re not trying to protect ourselves anymore.”

Back in 2004, Philippoussis dated an emerging 19-year-old songbird named Delta Goodrem, who sadly around this time received a Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosis. The tender support he provided during her treatment inspired one of her hit songs, “Out of the Blue”.

The Scud-Delta pairing didn’t last, and Philippoussis stayed a bachelor until 2013, when he married Romanian-born model Silvana Lovin. When we talk, their eighth wedding anniversary is a few days away. From the way he speaks about her, it’s plain he adores her and still pinches himself now and then to be sure the life they’ve created is real.

They have two children – Nicholas, seven, and Maia, three – and an old Malamute cross called Myka whom Philippoussis rescued in LA. Two years ago, the family upped sticks from San Diego to settle in Melbourne, where they lived in Williamstown, not far from Philippoussis’s boyhood home, until January, when the lure of coastal living in Jan Juc, near Torquay, proved irresistible.

“Our happy place is the ocean,” Philippoussis says. “Our happy place is barefoot on the sand.” For Philippoussis, it’s also on the tennis court, where you’ll find father and son rallying a few times a week. Nicholas is a natural athlete who’s playing better than he, Philippoussis, was at the same age, he says. Until recently, Philippoussis let his boy take the lead in terms of initiating practice, but of late he’s been pushing him just a little to hit before school, mainly to instil discipline in the lad, to get him in the habit of firing up early in the day.

I ask Philippoussis whether his dad, who to my eye always looked stern, even a little forbidding, pushed him. “No, or not until I told him at the age of 12 that I wanted to become a professional tennis player, and even then, not until physically I could be pushed, like 14 or 15,” he says. “Then he started to push me, and I’m glad he did. But he always gave me the option. He’d say: ‘You can stop playing whenever you want, but if you stop then you’ll go to school and when you’re finished, you’ll get a job and be like everyone else. This is your shot at something better. And if you choose this, I’m going to push you’. And I never wanted to stop.”

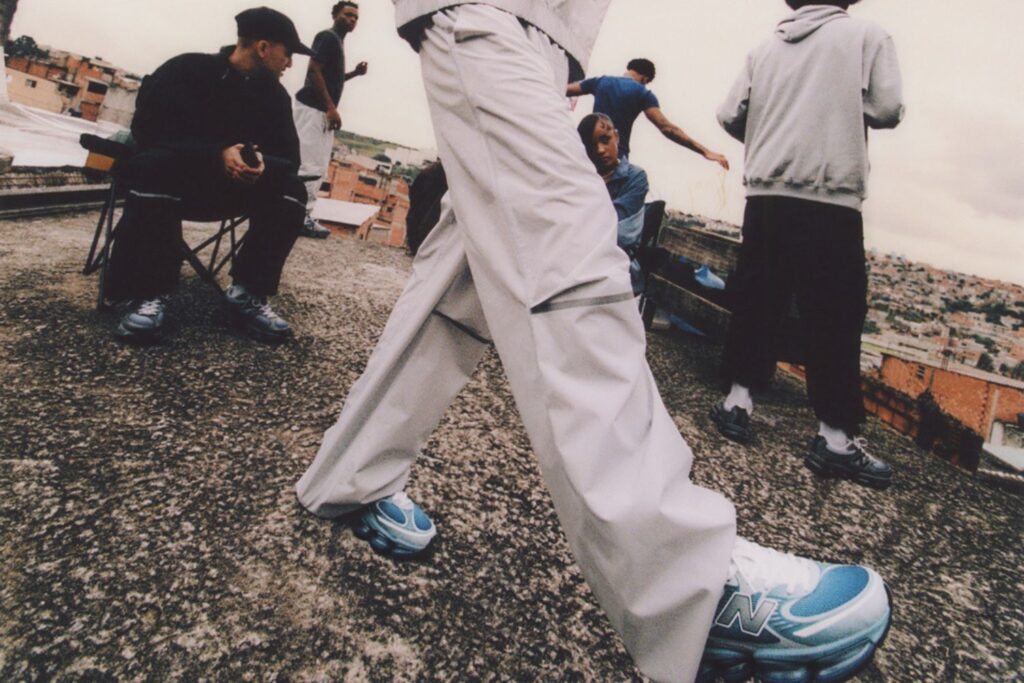

From the courts of pro tennis to family life, Philippoussis has recently split-stepped into the rag trade, launching his own label, AS WECREATE, m arketed as “consciously made luxury essentials” that include block-colour tees, sweatshirts and hoodies. After joining the pro tour in 1994, he tells me, he would sketch a lot in his spare time, which conjures up an intriguing image of a strapping figure in tennis whites bent over a pad. “I’ve always had a very strong creative itch. I’ve always had an appreciation for design, whether it’s a motorcycle, a car, a house, a building, whatever.”

When he returned to Australia in 2019, intent on getting his teeth into something, he decided that creating high-quality, ethically and locally made clothing was the ticket. “It’s early days,” he says, “but I have a big vision for this.”

SHADES OF GREY

As upbeat as he sounds, his reference to “personal pain . . . shit [that] happens” that never really leaves you, echoes in my head. For Philippoussis, life took an awful turn in July 2017, when the San Diego County Sherriff’s Department charged his father with child sex offences. The following year, a California judge dismissed the charges after Nick Philippoussis suffered a stroke while in jail awaiting trial. Gingerly, reluctantly, and only because I have some pretensions to being a proper journalist, I ask Philippoussis about his dad. How is he and what’s your relationship these days?

There’s a brief silence, during which I realise there’s every chance I’ve ruined a fellow man’s day. “Look,” he says, “the only thing I’m going to say is my dad had a stroke and he’s in an aged care facility close by us, and of course I visit him all the time.” Earlier, after Philippoussis had described surfing as his meditation, I’d asked him whether he was prone to bouts of melancholy. Sure, he said: now and then, as they do for everyone, things get to him. “But I won’t let it last long. It might be 30 minutes. It might be an hour.”

The alternative, he says – dwelling on something upsetting or perplexing – is a shortcut to torment, where one negative thought can trigger a cascade of gloom. “I’ve been there,” he says, “and I don’t want to go down that road again.”

And when our time’s up, the impression I’m left with is that Philippoussis truly is, by and large, a happy man, one who’s been able to let go of the thrills of top-level sport and settle for the quieter pleasures and arguably deeper satisfactions of family life. It’s the mark of a man. The mature man.

“I’m blessed,” he says. “Like, what is there not to be happy about? I’m married to a woman who, in my younger years, I could only have dreamt of meeting, and she is the mother of our two incredible children, who happened to be born healthy, and we live in a beautiful place in a beautiful country. Yes, my tennis career is over. But I still have the potential to build whatever I want. And so long as I have my wife and kids by my side, man, I’m capable of anything.”