Nedd Brockmann on what it takes to be relentless

The ex-sparky and PUMA athlete has a strict personal code that’s helped him achieve a series of jaw-dropping physical feats. He doesn’t expect you to run across a continent or subject yourself to overwhelming levels of pain and suffering, but he firmly believes we all have the capacity to achieve more than we think if we’re prepared to reach beyond our grasp and – here’s the hard part – refuse to give up

IT WAS AT the 8km mark of the Big 5 Marathon in South Africa back in June, when Nedd Brockmann stumbled into the kind of serious setback that’s made him Nedd Brockmann. Of course, it involved pain. Not the searing, relentless, fretting-for-your-future kind of pain Brockmann has dealt with in the past, but enough to give him pause. And, as he has so often in his life, the ex-sparky faced a decision: press on or pull out.

Brockmann, who was running the race as part of broadcaster Carrie Bickmore’s ‘Carrie’s Beanies 4 Brain Cancer’ charity team, had designs on the race record of 3.16.01. He’d told all and sundry upon his arrival of his intent to have a crack at the mark. Everything was going smoothly – four words that are so often a portent of disaster – when he rolled his ankle, causing him to “land funny” and break the cuboid bone in his foot.

For many of us – heck, most of us – there wouldn’t be a decision to make; such a serious setback would surely signal curtains. For Brockmann, it was the beginning of an intense five-minute dialogue with himself.

“I felt it at the time,” he says of the broken foot, which sees him sporting a moonboot and a set of crutches, as we chat outside a café in Sydney’s Randwick. “And then I just had to weigh up whether I have a broken foot and don’t finish the run or have a broken foot and finish the run. And for me, the easiest answer and the conversation I had was, It’s runnable, so let’s run on it. I made that decision and then it was like, Right, you’ve made the decision, so let’s get on with it and stop complaining. Of course it was hard. It always gets hard. This is what running is for me.”

If you know even a little about Brockmann, you’ll know that he finished the race. How, you might ask? The answer lies in the cold, hard calculus that drives his indomitable mindset. One that makes the answer a rather simple one: Brockmann had made the decision to try.

I REALLY DIDN’T want to be late to my interview with Brockmann. Nobody likes being late, of course, but these days, in an age of phones and quick ‘be there in 10’ texts, most people will cut you some slack. Brockmann won’t. I already know enough about the farm boy from Bedgerabong in NSW’s central west, to know that he won’t be so forgiving.

And so, as a wrong turn adds a precious few minutes to my journey to our scheduled appointment at 11 o’clock on a brisk Friday in June, I’m beginning to panic. This is a man who once upbraided a mate, who he was meeting for a run in Bondi, for being a couple of minutes late. It’s a minor detail, but one that tells you almost everything you need to know about Brockmann. Once he’s made a commitment to do something, he sees it through. Come. What. May.

Sure enough, as I pull into a car space on the stroke of 11, I catch a glimpse of Brockmann’s signature blonde mullet, as he sits at an outside table. I can’t be sure but as I approach, I think I see him glance at his watch.

“Here he is,” says the PUMA athlete, as we shake hands. I tell him about my anxiety about arriving on time. Brockmann’s eyes glint, traces of a grin cutting the corners of his mouth. “11.01 you were,” he says matter-of-factly.

So what, you might be thinking – I admit I was. But while tardiness might seem trifling to you or me, Brockmann ties punctuality to something more powerful and overarching: his value system. Once you make a decision to do something – be it meeting a mate for coffee or running across Australia, you enter – at least Brockmann does – into an ironclad agreement with yourself to honour it.

“There’s an intensity to that decision, always,” says the 26-year-old, who despite the crutches and moon boot is dressed like he’s ready for a trot in PUMA gear – grey singlet, black shorts, a cap and a bare, mud-stained foot (it’s probably worth mentioning that the wind has a Baltic chill today). “And I think it comes off quite jarring to a lot of people. But I will jar people for the rest of my life because what it comes down to for me is that very conscious decision. When someone says they’ll be there at 10, I say, no problem. That means 9.59, always. It’s not about time, it’s about respect. Once that decision’s made, there’s no backing out of it.”

This doesn’t mean Brockmann lives his life under the weight of self-imposed deadlines and commitments. He might not wash his dishes right away, for example. “But I haven’t made that decision that I have to have the dishes done that night,” he says. “It’s when I make the call and I say, Right, I’ll do this, that’s when I will try until it’s done.” Honouring these minor, everyday commitments, he adds, has a cumulative and pervasive impact on your psyche, forming a bedrock of residual grit you can draw on when things really do matter. “That’s how you get through a really hard thing because it’s in those moments, when you hit a wall or things pop up, that you have to rely on the fact that you’ve rocked up on time, or you’ve done this or that. Those all add up.”

YOU MIGHT BE familiar with the Nedd Brockmann story. If not, here’s a quick summary. Ex-sparky from the bush one day decides to start running . . . and never stops. He takes on ever more gruelling exercises in self-flagellation – running 60km from his farm to Forbes to get milk; running through the night from Sydney’s east to Palm Beach; running 200 laps of Bronte hill; running 50 marathons in 50 days to raise $100k for the Red Cross while continuing to work as a sparky; running across Australia in 47 days, four shy of the then record of 43, to raise $2m for the We Are Mobilise homeless charity. And last October, running 1000 miles around the track at Sydney Olympic Park, this time raising $4.8m for We Are Mobilise, with whom Brockmann is on a mission to raise $10m and transform the lives of 10,000 people by 2030.

Each quest represents a chapter in Brockmann’s life, and each, he makes a point to tell me, is one that’s now closed. He has no real interest, for example, in discussing the run across Australia.

“The run across Oz, to me, is going to the dog park with my dog two days ago,” he says, as we move tables to escape some noisy tourists. “No one gives a fuck. I wouldn’t be me if I was still bringing up the Oz Run.”

Indeed, he recoils at being associated solely with the remarkable feat. “When I get referred to as Nedd Brockmann who ran across Australia, I’m like, I’m just fucking Nedd. People in interviews ask me, ‘What do you want to be called?’ And I’m like, ‘Just Nedd Brockmann. Fucking ex-sparky’. I prefer that than ‘ultra-marathon runner, motivational speaker’, all that shit. It’s just not me.”

What Brockmann is happy to talk about is his ‘relationship’ with pain – you could call it an abusive one. He can still recall the agony of breaking his arm 20 odd years ago, his mum splinting the injury with two rulers, as she drove him into town, the damaged limb banging up and down with each bump in the road.

“I remember that so clearly and it was the worst thing ever,” he says, his eyes somewhere back in the family’s Nissan Patrol. He also recalls what his mum told him as a kid. “Not to be scared of pain but to embrace it and run towards it. It’s like you either shy away from it or you run fucking headfirst.” He’s charged toward it ever since.

He tells me about a video he’s seen of a five-year-old boy who has to get needles every week. “He’s sitting there and you can see the fear in his eyes, but instead of going, No, don’t do it, he’s going, ‘Yeah buddy, I love it, I love it’. Even though deep down he’s fucking shit scared.” Brockmann points down to his thigh. “I got goosebumps thinking about it, but that’s exactly how I think we all should either show our kids or tell ourselves. You must embrace it. It’s about making that conscious decision.”

Once you’ve made that decision, of course, you can expect to be challenged upon it, as pain, exhaustion and, perhaps most formidably, doubt, all take turns at battering your resolve. “I don’t ever think I’ll be at a point where I’m like Jesus Christ, it all went to plan, because I don’t think it ever does,” Brockmann says. “And I don’t think anyone who’s at the top of what they do can say that because if you can you’re not trying hard enough. You’ve always got to be on the edge of injury or the edge of breaking down. I’m probably a bit further on that edge a lot of the time.” But it’s on that edge, in that uncertainty, he says, that running’s “violent beauty” lies.

Brockmann points to the notorious ‘wall’ all runners must confront around the 30-kay mark in a marathon – typically a crucible of suffering and doubt – as an ordeal you have the potential to mentally reshape. “I think it’s not about letting the wall hit you, it’s about you kind of hitting the wall,” he says. “Instead of going, Oh no, it’s here, you’re like, Fuck yeah, it’s here. Instead of letting it crumble you, you crumble it.”

Brockmann may have a higher tolerance for pain than others. He’s as curious as anyone to find out. But at some point, he says, dealing with pain becomes a mental undertaking. “There’s a really weird hump you get over where it all becomes mental because you won’t feel any more pain than what you’ve felt.”

He describes himself as a “tough runner”. His goal now, though, is to become a “tough fast runner”, a quest that seems likely to shape his next big challenge. “I’ve got goals that keep me up at night and I think when something consumes every fibre of your being, you should fucking throw yourself at that. And for me, that is absolutely happening right now. I can’t wait to be a tough fast runner. I can’t wait to apply that toughness to intentional training.” He looks down at his moon boot. “That’s why the boot is a little frustrating. But it’s forced rest that I won’t give myself because I know how consumed I’ll be and how relentless I am in the pursuit of these things.”

You might ask at what point masochism turns into a flight, if not from madness, then mental turmoil. Much has been written about the high incidence of depression and anxiety among the ultrarunning community. The common trope is that participants are substituting an unhealthy vice – drugs, alcohol, addiction – for a healthier obsession. That they are running from their demons. I ask Brockmann if in running headlong into the pain cave, he might be fleeing something else?

“I’ve never gone out because I want to run away from something, I’m definitely running towards something,” he says levelly. If anything, he adds, running and the extreme nature of the challenges he takes on, have been the wild winds buffeting his psyche in recent years. “My mental state has been very volatile over the last few years because I’ve been dealing with extreme highs and extreme lows. It’s probably the running that’s brought it on more than anything else.”

I put it to Brockmann that for a man who’s structured his life around taking on feats that invite intense levels of pain and distress, his biggest challenge may lie in negotiating the humdrum nature of the day-to-day between his astounding quests. As Brockmann gives it some thought, I sheepishly make the comparison of a soldier between tours. Brockmann nods: “That’s what I was thinking about,” he says, admitting the military, with its discipline and rigid codes of behaviour, does hold some appeal for him.

“I’ve gotten better,” he says of the stretches between challenges. “I really struggled between the 50 maras and the Oz run, and then I really struggled between the Oz run and the 1000 miles, more because you put your body through so much torture that you then can’t physically do the thing you’ve spent all this time doing. My absolute biggest strength, without a doubt, is my biggest weakness. My inability to quit, my inability to slow down, favours me so much in life because I will not throw in the towel when you would expect someone would, but then that’s the problem.”

The weight of having to live this way, he says, is that you have to finish a marathon with a broken foot. “That’s the cost of that. But I wouldn’t change it for the world.”

***

A FEW WEEKS before our chat, another lone figure made the interminable crawl across the barren contours of the Nullarbor, from Perth to Bondi. This one also attracted public interest, perhaps not on the same scale as Brockmann did, yet the effort was notable for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, the British runner, Will Goodge, smashed the record by an astounding eight days. Secondly, unlike Brockmann, the Brit’s social output was characterised less by pain and suffering and more by frat boy humour. Goodge seemed to make a deliberate choice to document his odyssey with satirical posts that made light of the distress he was surely going through.

Brockmann has nothing but respect for the Englishman and his achievement, pointing out that Goodge’s comic underplaying was perhaps his way of dealing with the pain and the debilitating mental load of the challenge.

“I think Will was being very stoic and I know for a fact he was absolutely feeling it and humour could have been his way of dealing it,” says Brockmann. “That was the method to his madness.

I venture that Brockmann’s daily posting during his challenges is all the more powerful because it conveys something of what he’s going through, helping people feel a part of his journey. He shows them how hard it is.

This embrace of his vulnerability not only makes Brockmann relatable, it makes him authentic – it makes him, him. “I think I wouldn’t be vulnerable if I wasn’t being myself because I’m a vulnerable person,” he says. “I open up, I allow people in. I want people to see me. So, if I’m not showing the vulnerability, then I’m not showing myself.”

To the casual observer, Brockmann’s emotional nakedness might appear at odds with his toughness. It isn’t. “That’s where I think people are confused because usually in those times, they’re like, ‘Oh, he’s going to quit’. It’s like, No, I’m just fucking outpouring what’s going on internally and then I’m getting back on it because this is my way to release and get moving again. That’s being human. To remove that of yourself is to remove an amazing part of what it means to be human. So yeah, play on, I reckon.”

Any attempt to dissect Brockmann’s cut-through appeal must also account for the monumental nature of the challenges he takes on and the very real likelihood he’ll fall short, something to which he seems keenly aware. “When somebody knows they’re able to do something, no one gives a fuck,” he says. “People care when they think there’s no chance this fuck is going to do it.”

Indeed, it’s the prospect of failure, he continues, that turns a challenge into something character defining, possibly life affirming. “That’s why it scares the shit out of me telling the world what I’m going to do because it means there’s no way out,” he says. “I set myself up for failure, in that regard, because very few people will ever take something on without knowing they can do it. That’s where the courage is.”

A FEW WEEKS before, Brockmann is at Men’s Health’s photo shoot. The photographer is instructing him to run down an alley, hoping to catch the late afternoon sun on the runner’s shoulders. Brockmann obliges, over and over again, until the photographer looks up from his camera and asks his assistants to reverse the angle and remove some of the weeds and rubbish lying in a gutter where Brockmann will run.

Before the assistants can move, Brockmann has sprung into action, pulling up weeds like an over-eager dad at a school working bee. There’s knowing smiles among his team – the day has been punctuated by frequent ‘Brockmannisms’.

“C’mon, let’s go,” he had said, clapping his hands as he emerged from the change room in PUMA gear earlier in the day. Later, he starts banging out push-ups before I tell him the next shot isn’t shirtless. “I know, mate. I’m just doing my thing. Don’t worry about me.”

It’s all unaffected. He’s gruff at times, grinning and cracking jokes at others. The temptation is to reduce him to an archetype or even a caricature – the larrikin who became a folk hero; the old school bloke-from-the-bush who swears like a trooper and used to work on the tools. If you didn’t know better you might think he’s playing a character, one with the unlikely, slightly cartoonish name of Nedd Brockmann. A myth, or even a meme, rather than a man.

That’s perhaps the risk you invite by putting yourself out there – maggot-ridden toenails and all – on social media, as Brockmann does during his challenges. He regards social as a necessary evil – at one point he picks up his phone as if he’s about to fling it into the passing traffic, as he rails against our collective obsession with ‘engagement’. At the same time, he recognises social platforms are a powerful tool in his mission to help the homeless.

But gee, it’s tough at times. While casual drive-bys from keyboard snipers are par for the course for any public figure, Brockmann admits the animosity he received upon announcing his quest to run a thousand miles in 10 days reached another level. The main gripe – mostly from within the ultrarunning crowd – was that once again, he had no business attempting the epic feat, at such a young age, with so little relative running experience behind him.

“It was like, Fuck you, you’re a cocky prick. You don’t deserve to even be out there. Of course, as a human being who cares and is so emotional and gives people so much, you are going to get affected by that.”

His response to the vitriol might surprise you, drawing as it does on an objective, almost Buddhist level of detachment that’s beyond most of us, and you would think, someone as emotionally raw as Brockmann often is. “I went through a very, very powerful transition over about two months where I had to look at it from a very third person, bird’s eye view, where you can’t listen to someone saying, You’re a hero, you’re amazing, without also listening to someone saying, You’re a flog, I fucking hate you. You have to take them all as a grain of salt. Take ’em all in or take none of them in.”

The epiphany came when he recognised the brittle, often empty space the negativity was coming from. “It’s just projection,” he says. “It’s just these people projecting their own insecurities onto you. It’s fascinating, these people, these faceless people. I’ve never in my life ever had someone come up to me in the street and go, ‘Nedd, you’re a fucking cocky prick’. If they did, I would actually respect the fuck out of it.”

The truth is, that’s unlikely to happen, for Brockmann is essentially the antithesis of the keyboard warrior. He and they reside at opposite ends of the digital devices that rule our lives. He’s a doer, not a talker, an avatar of possibility rather than an anonymous digital denigrator, a poppy to their shapeless secateurs. But what really separates him from them and, indeed, many of us who watch on from life’s sidelines, is that he has a go. And he refuses to give up.

That Big 5 marathon? Brockmann would claim the record with 30 seconds to spare . . . on a broken foot! The funny thing about that is the record marked one of the few times he’s actually achieved his stated goal. In taking on the near-impossible, Brockmann has failed as often as he’s succeeded and yet his legend (a phrase he’d surely baulk at, hinting as it does, at a larger-than-life figure when he’s just a fucking ex-sparky!) only grows.

“I think there’s something in me that’s wanted and always will want, to strive and fail but try at all costs,” he says. “And I think a lot of us get to a point where we want to stop trying because something has defeated us, or we didn’t win. I think that’s maybe what got me to this point because I’m relentless in my desire to continue to try. I think that the trying part is the difference because there’s no end to that. You can always try.”

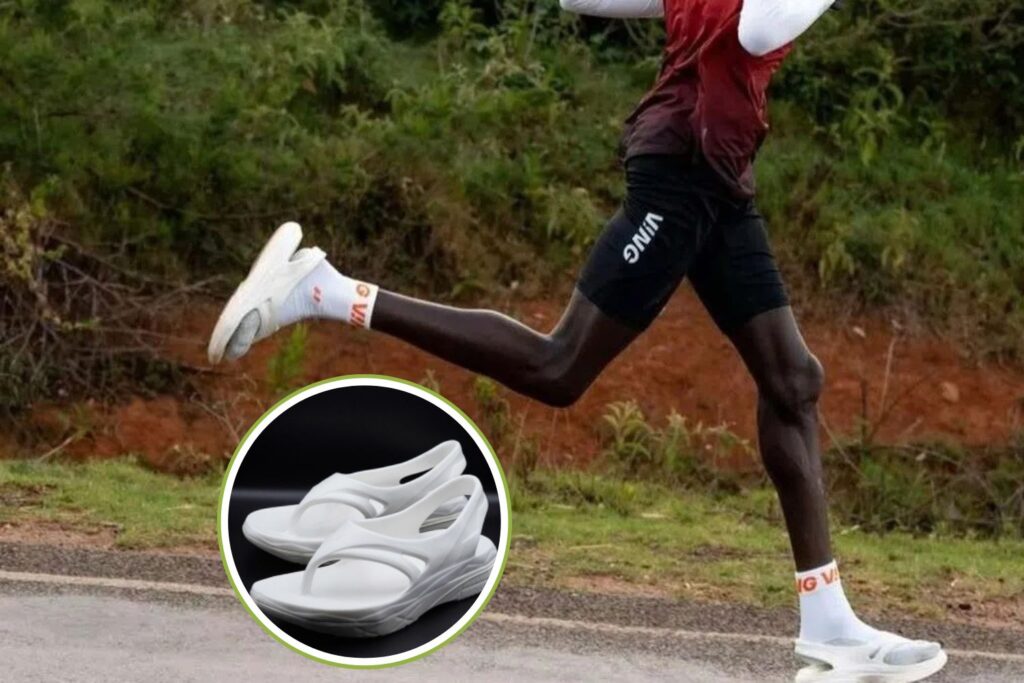

Nedd wears PUMA Velocity NITRO 4 shoes and PUMA shorts – available at Rebel Sport. Opening image: all clothes by PUMA – available at Rebel Sport.

Words: Ben Jhoty

Photography: Michael Comninus

Production Director: Rebecca Moore

Fashion Assistant: Kailee Waller

Digital Director: Arielle Katos

Art Direction: Evan Lawrence

Hair: Darren Summors

Makeup: Vanessa Barney

Video: Jasper Karolewski