THE CLOUDY SKY CLEARS for the first time all day, as I make my way to the starting line of the Adidas’ Road to Records 2025. The chill of the overcast morning is giving way to crisp beams of sunlight, hitting me like a jolt of energy. Around me, elite athletes and hobby joggers alike are making their final preparations before an all-out 5K on a course built for speed. I’m not just here to watch. I’m about to experience this elite racing event from the inside out.

Just a week earlier an ill-advised long run left me hobbling around with a case of ilio-tibial band syndrome (ITBS). When I arrived at Adidas’ global headquarters just outside of the small Bavarian town of Herzogenaurach – which I still can’t pronounce – I was convinced I would be unable to participate in Road to Records’ closing race.

The thought of travelling all the way to Germany – 36 hours of travel from Sydney, in total – only to be a spectator gnawed at me. But the thought of competing only to pull out halfway through, or worse, to finish towards the back of the pack on a simple 5K, was similarly off-putting.

So, how exactly did I end up on the starting line confident that I was about to set a new PB? Well, it has something to do with what Kenyan runner Agnes Jebet Ngetich told me right after breaking the women-only 10km world record a few hours before my race. “Coming here today, there was no pressure,” she said. “I knew that I could run this time. And look around at this place, I have to give 100 per cent while I’m here.”

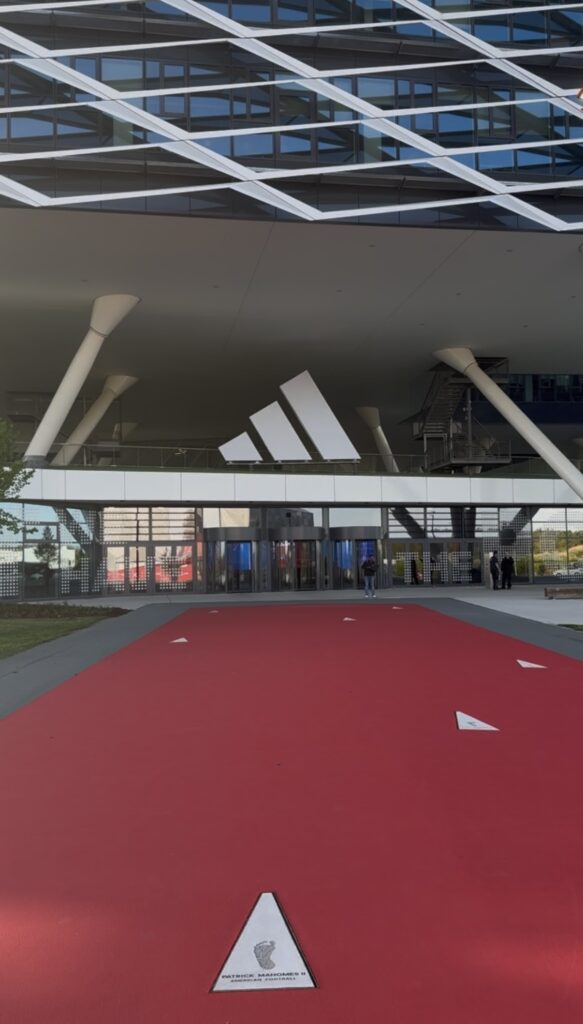

It is true that Adidas HQ does inspire a high level of confidence. Maybe there’s something in the air, or maybe it’s a product of the cohort effect, but once you step onto the campus at Herzogenaurach, it’s difficult not to feel inspired.

Arriving at the sprawling Adidas HQ campus felt like stepping into the temple of a religion dedicated to the worship of athletic excellence. Set amidst the rolling fields of Bavaria and Franconia, the modern architecture of the facilities are hard to miss amid the peaceful countryside.

As I approach the entry of the campus, one of my travelling companions asks our shuttle driver what the purpose of the futuristic, important-looking building we had just passed is. “I think it’s a car park” the driver responds without undue emphasis. It’s an easy mistake to make, though, as the sleek glass buildings and prismatic reflections they cast across manicured lawns do create a certain ineffable buzz in the air that makes it feel as if every detail of the campus – even the car parks – are driving athletes towards Olympic medals and world championships.

Once I made it to my room, I was immediately kitted out with Adidas’ latest performance gear. The all-red Adizero racing kit – including a razor-thin singlet, featherlight track shorts, rain jackets, technical socks and a number of running shoes – looks exactly like what rising sprint sensation and Adidas athlete Gout Gout wears at his meets. Needless to say, but it was probably overkill for me to be wearing it, but I’m not one to pass over any advantage to be had from hi-tech innovative gear.

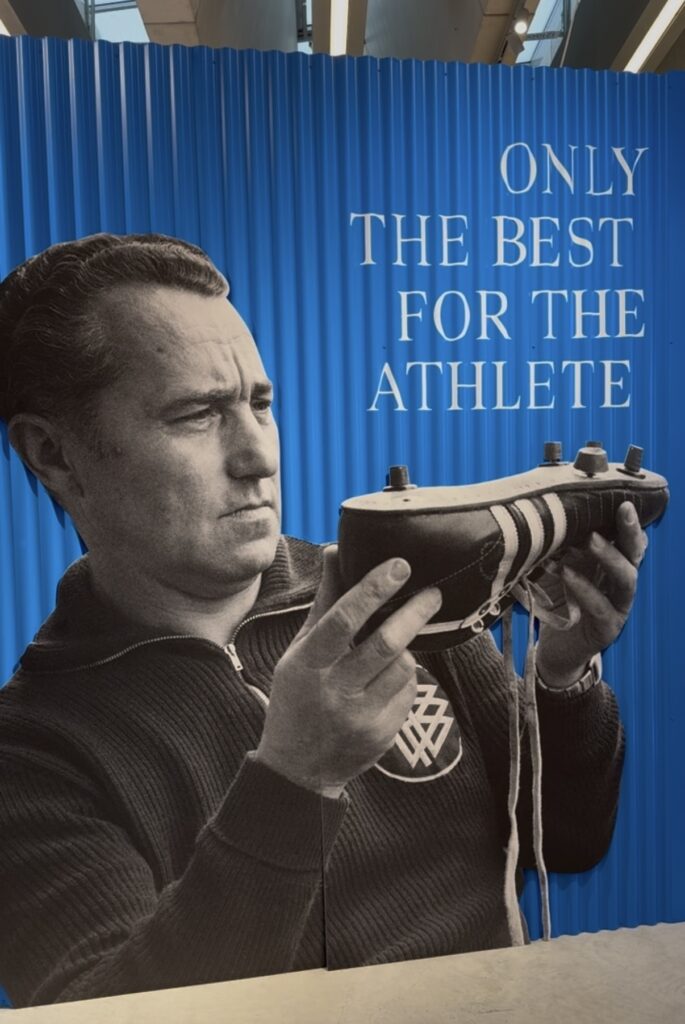

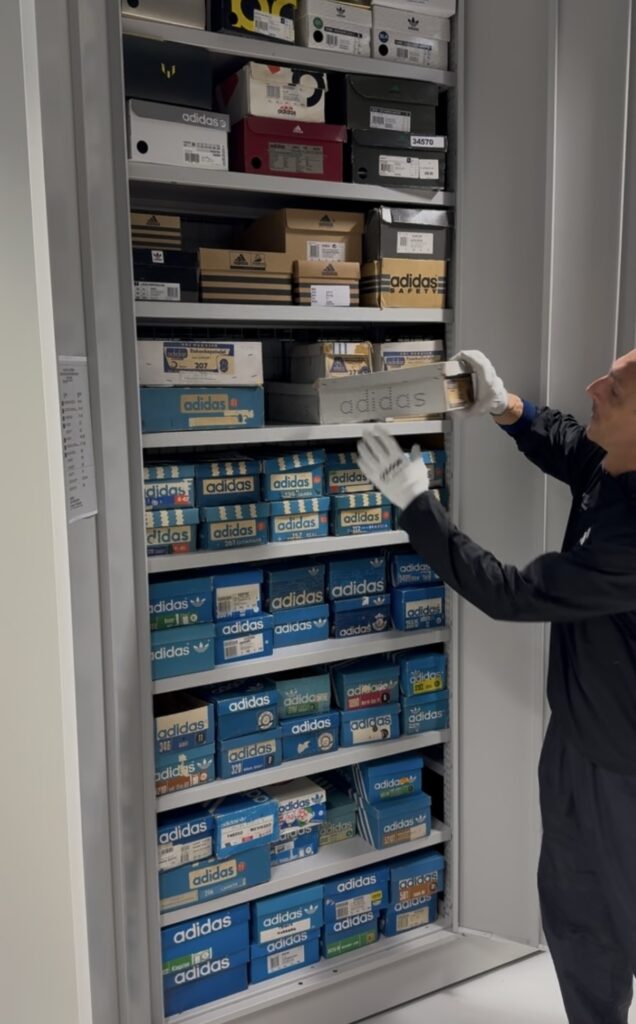

First on the itinerary was a visit to the Adidas archive – a trove of shoes and apparel from famous historical sporting moments. Everything from the Adidas Supernovas Haile Gebrselassie wore while setting the marathon world record to the signature shoes Adidas created for NBA MVP Derrick Rose are on display.

The archive also houses early iterations of the Adizero line, marathon flats that pushed boundaries long before carbon plates became the norm, and just about every Adidas shoe that was worn by an athlete setting a world record. The records have poured in since the release of the Adizero Adios Pro Evo 1 in 2023 and the archive is rapidly filling up. The lightest running shoe ever made, the Pro Evo 1 was used to set the women’s marathon and 10km world records and was also worn by three of the top four finishers at the men’s Olympic marathon in 2024.

At the centre of a separate on-site archival exhibition is a shrine celebrating every world record set at Road to Records. So far, the exhibit holds three shoes, but next year it will need to make room for a fourth after Agnes Ngetich broke the women’s 10km world record just a day after my visit.

Here again the Pro Evo 1 came to my attention when an archivist told me the shoe was frequently the cause of distress for her. This is due to the shoe being so lightweight that when she picks up a box with the Pro Evo 1 supposedly inside, she usually assumes that the box must be empty and that the shoes have been misplaced.

At the centre of a separate on-site archival exhibition is a shrine celebrating every world record set at Road to Records. So far, the exhibit holds three shoes, but next year it will need to make room for a fourth after Ngetich’s new women’s 10km world record set just a day after my visit.

Here again the Pro Evo 1 came to my attention when an archivist told me the shoe was frequently the cause of distress for her. That’s because the shoe is so lightweight that when she picks up a box with the shoe supposedly inside, she assumes that the box must be empty and that the shoes have been misplaced.

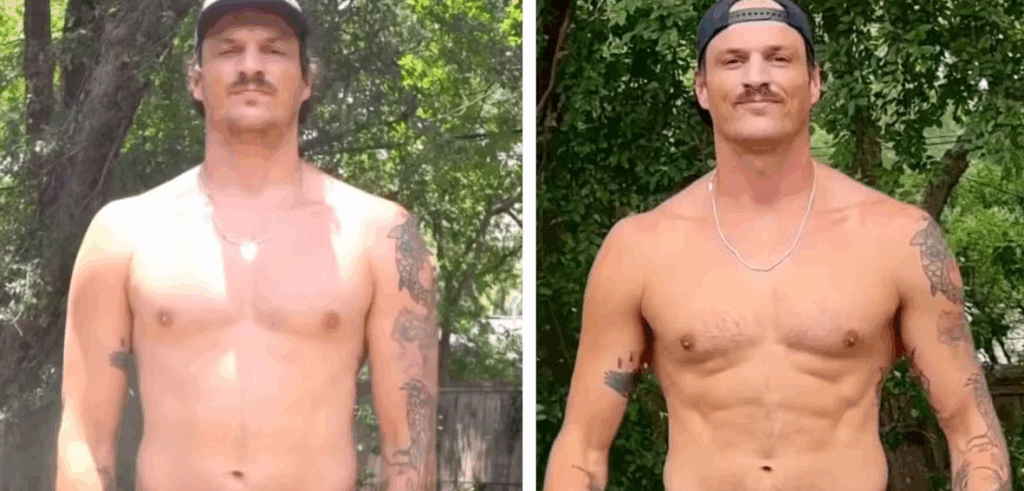

Next came an even deeper dive into performance in the form of lab testing. Under the watchful eyes of Adidas’ sports scientists, I underwent a full body composition scan, biomechanical gait analysis, lactate threshold testing and treadmill sessions in prototype shoes.

The body scan revealed the inner blueprint of my body, including bone density, muscle distribution and fat percentages. I didn’t know what to make of most of the data, but I feel better informed nonetheless. The most interesting takeaway, however, was that my right foot is a full shoe size larger than my left. Now I’m not sure what size shoes I should be wearing – but surely it’s better to be a size too big than a size too small, right?

During my treadmill sessions, sensors tracked every stride and force pattern with forensic detail. The results painted a complete picture of my current fitness levels, running economy and VO2 max.

Running in the prototype models was interesting to say the least. I wasn’t allowed to know the names of the models – presumably to prevent me from telling all of Adidas’ secrets to a rival brand – but one version offered an almost eerie sense of forward propulsion, the kind that made 3:45/km pace feel, if not easy, at least sustainable for stretches. Another focused more on stability, a crucial factor given my recent ITBS injury. The scientists explained every reading, connecting the data to my movement patterns in real time and using my feedback to improve the shoes.

Among the most exciting parts of the week was getting an exclusive first look at the new Adizero Adios Pro Evo 2. In case you’re unfamiliar, Adizero is the elite branch of Adidas running shoes, and the Adios Pro Evo is the pinnacle of Adidas innovation. As previously mentioned, the Evo 1 has helped athletes break world records, win gold medals and has established itself as the world’s best running shoe. This makes the Evo 2 – which releases in Australia on May 1 – perhaps the most highly anticipated shoe of the decade.

Stripped down to just 138 grams – lighter than most track spikes – holding the Evo 2 felt like holding a piece of paper. The outsole has been reworked to shed even more weight while adding more traction. The revamped Lightstrike Pro foam is softer, but feels more resilient, delivering five per cent more energy return than the Evo 1. Given the record-breaking precedent set by the Evo 1, that stat should tell you that a few more records are about to fall. Carbon-infused EnergyRods run along the length of the midsole, fine-tuned to work with the foot’s natural motion and provide further propulsion.

Wearing the Evo 2 made me feel almost disconnected from the ground. Every step seemed to spring me forward, reducing ground contact time and keeping momentum high. Holding the Evo 2 in my hands, feeling the impossibly light weight and the barely-there upper, I realised how much of a revelation this shoe is going to be. It’s not just an astounding technical leap forward, it is going to rewrite what we think is possible in running.

It was around this time that I not only decided that I would run in the event-closing 5K, but that I would at least attempt to do well. Being confronted with all the greatness and innovation surrounding me, it was difficult not to be inspired.

The next day was race day, and the atmosphere was electric. A DJ spun high-energy beats, crowds lined the course and banners emblazoned with ‘Road to Records’ snapped in the breeze. Early in the morning, the crowds witnessed Agnes Ngetich break the women-only 10km world record, followed by Hawi Abera Kumsa, who smashed the women’s under-20 world record in the one mile, and Phanuel Kipkosgei, who did the same in the men’s one mile.

As I edged closer to the start of my race, doubt started set in. Was I just going to pull out after a few kilometres if the pain became unbearable? I thought to myself. Then, ducking through the crowd in the distance, I spotted the 162 centimetre frame of Ethiopian running legend Haile Gebrselassie.

A two-time Olympic gold medallist in the 10,000m and a former marathon world record holder, Haile ‘The Emperor’ Gebrselassie is the stuff of legend in the running world. He was a paragon of elite performance for two decades and despite now being 52 years old, he finished in the top five at the Tokyo marathon as recently as 2012 and still holds the marathon world record in the masters division for athletes over 35. And here he was beelining towards me.

I stopped Gebrselassie to ask him for a picture – unsure whether it was right to address him as ‘Emperor’ or not. He asked me if I was going in the 5K before wishing me good luck and telling me that he too would be participating. Surprisingly, that was the spark I needed. If I could beat a legend like Gebrselassie, even if he retired years ago, imagine the bragging rights it would give me.

A few minutes later I was toeing the starting line. Heart hammering, adrenaline spiking. This was it. The starting gun fired, and the crowd surged forward. I passed Gebrselassie in the first 100 metres and found myself in a clearing, too far behind the elite athletes to mount a chase, but too far ahead of the pack to form a pace group. So, I settled into my stride.

The first kilometre felt effortless. The smooth tarmac of the Adidas campus seemed conducive to speed. But lurking in the back of my mind was the injury. 2.5km in, I felt a twinge of tightness on the outside of my knee. Panic fluttered briefly in my chest, but I leaned into the discomfort, told myself to focus on the next 500 metres, not the next two kilometres.

By the 4km mark, it became a mental battle. Every stride burned. My lungs screamed for relief. I rounded the final bend, drove my arms harder, legs turning over like pistons as the finish line approached in a blur of sound and colour. I crossed it gasping, elated, and glanced at my watch: 19:50. I had run a personal best time.

While it would be bordering on insanity to call my PB a product of, for lack of a better term, the aura of Adidas HQ, I would be lying if I said the atmosphere in Herzogenaurach didn’t play a part in my result. I started the week thinking I wouldn’t even enter the race and came away with a PB. Without the events that filled the week, I doubt that would have happened – it also likely wouldn’t have happened if I didn’t have the very best gear to assist me.

Earlier in the week, I learnt that Adidas’ design philosophy centres on the belief that its consumer base can be divided into two categories: the many and the few. The few are the elite athletes who are out there pushing the boundaries of what is humanly possible and need the best possible performance gear to do so. The many are, well, the rest of us who buy Adidas products. We aren’t necessarily gifted athletes, but we still want the best gear and are capable of pushing our own personal boundaries.

At Road to Records 2025, I learnt that breakthroughs aren’t reserved for the gifted few. They’re available to anyone willing to show up, face a challenge, and run toward it. Road to Records lit a fire. It’s up to me to keep it burning.