THE DAY JOE Breen realised he had a problem, he was standing at the top of the stairs in his Massachusetts home during a classic case of man vs. spider web, trying to get rid of the unwelcome visitor near the ceiling. As he remembers it, he was using a broom to sweep the web out, bumbling about in the same way anyone who has ever used a broom for its unintended purpose might. What he didn’t know was that at the bottom of the stairs, his wife was recording him.

“It was just really painful to look at,” Breen, 38, recalls of the video shot in late 2021. The footage showed a precarious situation—a clearly impaired man, wobbling on his tiptoes atop the staircase, occasionally falling against the wall as he balanced the broom, himself, and the effects of the bottle of vodka he’d started drinking earlier that day. “That was the first time I really saw from the outside in. I’m slurring every word I’m trying to say. In my head I’m fully comprehensible—full sentences, everything’s good. But then I realise I’m speaking complete gibberish.”

Standing 5′8″ and weighing in at 150 kg, Breen had always been a big guy. He was also a regular drinker, though it had never been a “problem,” per se. That changed when the pandemic hit. He had already been dealing with a lot of stress between navigating his career as an emergency medical dispatcher and raising a daughter with autism. Add a global health crisis, and an evening cocktail turned into two or three. Then cocktails turned into bottles. At one point, Breen remembers picking up a bottle of vodka at the store to quietly replace an empty one at home. But before he made it back inside, he decided to open it up in the driveway. The more he drank, the more he became dependent on it, while also packing on a bunch of empty calories that contributed to ongoing weight issues.

“I would have days where I’d have the day off from work, I would drop [my] kid off at school, then I’d go home and immediately make a drink for myself,” he remembers. “I would think, Oh, well, hey, I’ve got seven hours till the kid’s home, so I got plenty of time to have a couple drinks now, sleep for a bit, and be an adult for the rest of the day. It was this cycle that just kept going on and on.”

While Breen says the drinking didn’t necessarily interfere with work or other obligations (so he thinks), it did take up most of his brain space, as he constantly thought about when and how he’d have his next drink. After watching that video, he also had another harrowing realisation: He was beginning to follow in his father’s footsteps. “My father was an alcoholic, but he was an abusive alcoholic, so I kind of always swore to myself, even though they say that stuff’s genetic, like, Oh, that’ll never happen to me. I’ll never let it get to that point. And it never got to an abusive point, obviously, because that’d be a whole different conversation, but I didn’t expect the drinking to catch up to me like it did and suddenly take ahold of my life.”

Before: Breen in May 2019 during one of his heaviest periods, at 142 kg. After: Breen five years later in August 2024, 174 kg.

Fed up with the hold alcohol had on him, Breen at first thought he could curb his desire to drink by sheer willpower. “I was the cliché person who said I can stop anytime I want—I don’t need to drink,” he says. “I was in complete denial. I’d say, I only had one drink tonight, when really I knew it was my second or third. But in my head I was saying, I’m cutting back—I made this less strong than usual. I knew that wasn’t going to fully cut it.”

After those failed attempts, Breen talked to his doctor about his alcoholism, also known as alcohol use disorder (AUD). The doctor referred him to a local clinic, where the provider recommended therapy and prescribed him a common first-line treatment, a medication called naltrexone. Originally approved for medical use in the U.S. in 1984 to treat heroin addiction and available to treat AUD since 1994, the drug binds to opioid receptors, part of the body’s system for regulating pain, reward, and addictive behaviours. For some people, it’s able to help them totally abstain from alcohol. For others, it reduces alcohol consumption and the cravings that trigger binge use or relapses. Naltrexone is one of three standard FDA-approved medications currently on the market to treat AUD. There’s also disulfiram, which causes people to feel violently ill if they consume alcohol while on it, and acamprosate, which is believed to treat the imbalance of neurotransmitters in the brain following chronic alcohol consumption and can help reduce the brain’s dependence on alcohol, though the exact mechanism is still not fully understood.

One of the benefits of naltrexone is that it can be given to people while they’re still drinking, unlike the other medications, which require total abstinence from alcohol. Though as Breen quickly learned, this can create a false sense of control. While taking the drug, he cut back from multiple bottles of liquor a week to a few drinks a week. Around six months in, he figured he was in the clear and, with his doctor’s consent, he stopped taking naltrexone completely. That’s when the drinking kicked back into high gear. At first he snuck a drink here and there—trying to do it more carefully this time, so as not to blow his cover—before eventually throwing back shots again.

Now dealing with high blood pressure, additional weight gain, and an alcohol problem that was putting a strain on his relationship with his wife, Breen decided to get himself in check and address his overall health. For him, that began with managing his weight. At the time, his wife had found success with Saxenda, a drug whose active ingredient, liraglutide, is FDA-approved for chronic weight management. Encouraged by her weight-loss progress, Breen decided to give another member of this class of drugs, known as GLP-1 agonists, a shot. Eight months after he stopped taking naltrexone, in April 2023, his primary care doctor prescribed him Wegovy, a brand name for semaglutide (the same active ingredient in Ozempic), which is FDA-approved for chronic weight management. As the pounds started to drop (he lost 20 in the first month), Breen experienced a completely unexpected side effect: His desire to drink diminished almost completely. At first he had a day or two when he occasionally snuck a drink, but as the medication began to suppress his hunger, it also took away his cravings for alcohol.

Breen is not alone. Reddit and TikTok are teeming with stories from people whose experiences with GLP-1s like Ozempic and Wegovy, as well as Mounjaro and Zepbound (tirzepatide), have radically changed their relationship with alcohol. And while the FDA has not approved semaglutide or tirzepatide for treating AUD—which 28.9 million people in the U.S. age 12 and older have reported they’ve struggled with in the past year—the medical community is well aware that these drugs have a potential use in treating addiction, from alcohol to opioids and other narcotics.

This would be revolutionary for people struggling with alcoholism. Today, there’s an urgent need for new forms of treatment. Deaths from excessive alcohol use have risen in the U.S. in the past two decades, with a 49 per cent increase from 2016 to 2021 alone. But addiction treatment is complex. Society has long believed that addiction is a moral problem when it is, in fact, a very real disease with biological risk factors like genetics, psychological risk factors like early childhood trauma, and sociological or environmental risk factors like poverty and unemployment, explains Anna Lembke, MD, a professor of psychiatry and addiction medicine at Stanford University and the author of Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence. Treatment often requires addressing these biopsychosocial factors with a combination of medication, therapy, and 12-step programs (hence why it’s so complex), and it’s estimated that two-thirds of people relapse within the first six months. Now scientists and researchers are looking at the very real possibility that, for people like Breen, GLP-1s could be the missing piece of the treatment puzzle they’ve been waiting for.

The medical community first showed interest in the potential of GLP-1s in treating alcohol addiction when the drugs proved effective with obesity in 2014. Since ingesting food and alcohol both involve the interaction of the body’s cells with carbohydrates, it’s common for people with alcohol use disorder to also struggle with carbohydrate addiction (aka processed food addiction). Though that relationship is still being investigated, essentially the inability to control the impulse to eat a big piece of pie despite being full is the same kind of inability that may fuel binge drinking and other addictive behaviors. As GLP-1s gained widespread popularity over the past few years, thousands of people began to share their experiences with reduced alcohol cravings on social media, with some even saying the drug completely eliminated their desire to drink. This anecdotal evidence validated the need for additional research to understand just how life-changing these drugs could be for treating AUD.

Studies conducted over the past decade in the U.S. and internationally have already shown promising results. Early evidence dating back to 2015 demonstrated that GLP-1s reduced alcohol dependence in rodents and monkeys. In recent years, research has started to focus on human clinical trials and the analysis of patient health records. One National Institutes of Health study tracked over 80,000 electronic health records of patients with obesity and no prior diagnosis of AUD. After a year, the people receiving semaglutide had a 50 per cent lower risk of AUD diagnosis and a 60 per cent reduced risk of recurring AUD compared with the group that didn’t receive the drug. In Denmark, a 2022 study revealed that GLP-1s significantly reduced alcohol consumption in thousands of adults within the first three months of starting the drug compared with another medication. However, it also suggested that positive results could be partially attributed to lifestyle changes made while on the drug, like more frequent doctor visits. This past summer, the University of North Carolina School of Medicine presented early findings from the first completed randomized controlled trial of semaglutide in 48 people with AUD, which showed that those taking the medication reduced their drinking quantity and their heavy drinking more than a placebo group. And, most recently, an analysis of the electronic health records of 817,309 patients with a history of AUD from January 2014 to August 2022 found that those taking GLP-1s experienced lower rates of alcohol intoxication.

Currently, the pharmaceutical companies behind these drugs are staying relatively mum about this early research. When contacted for comment, a representative for Novo Nordisk (which makes the semaglutide medications Ozempic, Wegovy, and Rybelsus) told Men’s Health via email, “Novo Nordisk welcomes independent research investigating the safety, efficacy, and clinical utility of our products. However, none of our semaglutide-containing products are indicated for the treatment of addiction-related illnesses. Importantly, our clinical studies have not been designed to assess the effectiveness of semaglutide on alcohol use disorder or other addiction-related illnesses.”

Similarly, representatives for Eli Lilly (the tirzepatide medications Mounjaro and Zepbound) responded, “Lilly collects and evaluates data about its medicines to see where they may provide benefit beyond their current indications.” The company did not respond to a request for comment about internal research, the ability to keep up with demand, or the drugs’ potential uses outside of glucose and weight management.

Despite this ambiguity from the drug companies, the science behind this growing medical hypothesis is not far divorced from the science that cleared the use of GLP-1s to treat diabetes and weight management in the first place. GLP-1 agonists are a class of drugs that mimic the natural GLP-1 hormone in the body. They help manage diabetes and weight by releasing insulin, slowing digestion, and increasing feelings of fullness. In the brain, GLP-1 interacts with the hypothalamus, which regulates hunger and other bodily functions. By activating receptors in this area, GLP-1 influences “reward behavior,” affecting how we experience pleasure from food and, potentially, alcohol.

“Naltrexone is a useful medication for some people, but it doesn’t work for others. I suspect it will be the same for GLP-1s,” says Dr. Lembke. “Some people will find them helpful for AUD. Others not. Which is why we need more medications that work by a variety of different mechanisms to address the diversity of brains. We have to tackle this problem from many different angles.”

In addition to the specific way these drugs interact with the brain, another difference between GLP-1s and existing forms of addiction treatment is that they have less of a stigma. That’s because they’ve already been so widely accepted in treating diabetes and obesity. “It also has this added benefit of weight loss, which is a socially incentivizing side effect that, especially for people who are overweight and alcohol addicted, may be really appealing,” explains Dr. Lembke. “It may in fact even work better in people who are obese and addicted to alcohol compared to people who are not obese and addicted.”

Dr. Lembke is referring to a 2022 study in Denmark that examined how people with alcohol use disorder respond to a GLP-1 medication versus a sugar pill while also receiving cognitive behavioural therapy. Overall, the research didn’t find that the GLP-1 was superior to the placebo at six months after treatment. Interestingly, however, the participants who were also obese did show a significant reduction in heavy drinking days and total alcohol consumption. This may mean that these drugs work best against alcohol addiction in a specific, albeit widespread, group of people.

There’s a long way to go until we get to that point, though. Researchers are still conducting clinical trials that will test whether or not semaglutide can be an effective new treatment for AUD. In order for GLP-1s to gain FDA approval for this use, they must go through two well-designed (large, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled) phase 3 clinical trials that, ideally, run for 6 to 12 months. After the results are submitted to the agency, the FDA would review the results, as well as the drug’s positive and negative effects, the treatments currently available for the proposed use, and more. Successfully getting these drugs on the market for AUD treatment could take years, if it happens at all.

A key factor—or lack thereof—in this is the pharmaceutical companies, which are not exactly jumping on board to fund these very expensive studies. “Running clinical trials for a specific addiction indication would cost them a lot of money,” says Dr. Lembke. “It really may not be worth it to them, since they already have FDA approval and since doctors commonly prescribe off-label, especially for mental health disorders. It’s very common to do that even without a specific FDA approval indication.”

While we await the results of these trials, we also need to contend with some hard truths. Namely, we still aren’t even sure of the long-term effects of GLP-1s on the body. We already know the short-term side effects that patients taking these drugs to lose weight have experienced: nausea, vomiting, bloating, and some more extreme (albeit rare) things like bowel obstruction, pancreatitis, and stomach paralysis. But how do they impact us in the long run? And can older heavy drinkers, who already have an increased risk of muscle loss, handle the substantial muscle loss that comes with shedding a significant amount of weight in a short amount of time? There’s also the danger of patients regaining the weight or, worse, suffering an AUD relapse when they either choose to go off the drug or have no choice but to go off, due to, say, an employment change and loss of insurance coverage for the medication.

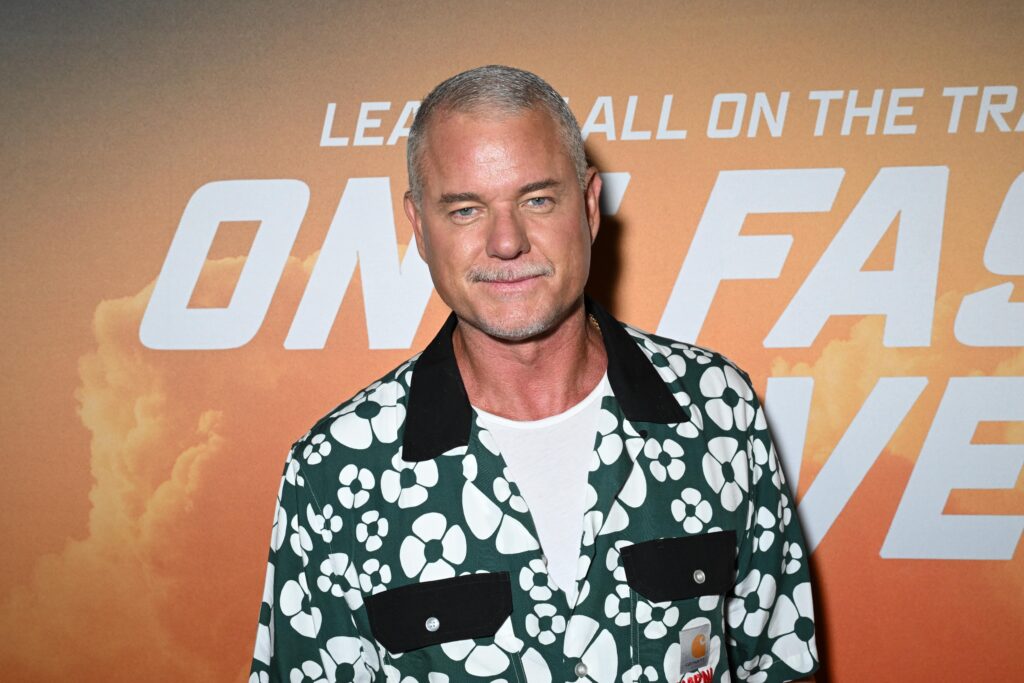

Breen post-run at the Lowell Firefighters Road Race in Massachusetts with his 6-year-old daughter, Luna, in October 2024.

For all of the remaining challenges and unanswered questions surrounding GLP-1s’ role in addiction treatment, what is clear is that they’re not the silver bullet that people expect or want them to be—at least not yet. As those who have taken the drugs know, they function best with a multifaceted approach to whatever they’re being used for: managing weight, controlling type 2 diabetes, or, yes, potentially treating addiction.

Two years ago, Breen had a body mass index of 50 and an alcohol problem. Since starting Wegovy in April 2023, he has lost a staggering 180 pounds, currently weighing in at around 155, and cut his BMI by more than half to 24.3. The drug gave Breen the ability to better focus on exercise and talk therapy, while it curbed his impulses to drink and eat. There was once a world where he couldn’t have imagined completing a 5K, let alone doing so in 40 minutes. “I can jog a 13:20 mile now, which I still laugh at,” he says. “I’m doing a 5K in another two weeks, and I’ve already joked to my coworkers, ‘I’ll see you guys at the finish line—I’ll be the last one there.’”

These days, Breen reserves drinking for social events with friends, like weddings or parties. He’s able to go out and enjoy the social aspect of drinking without feeling compelled to have another drink when he gets home. He’s even able to keep a bottle of Tito’s on top of the refrigerator without touching it, no matter how bad his day was.

For Breen, therapy has been a meaningful resource alongside Wegovy to manage his alcohol addiction. For others, a more intensive solution, like rehab, may be necessary. Whichever approach a person takes, mental and emotional support is critical to a successful long-term recovery, and these drugs can, hopefully, play a big part in that recovery, both now and in the future.

“Now that I have a kid—you know, the dad card thing—you look at life a lot differently,” Breen explains. “I want the world to be a better place in general, and if [these drugs] stymie alcoholism, the ripple effects that can have in society… you can’t understate how that can help across the board.”

This article originally appeared on Men’s Health US.

Related: