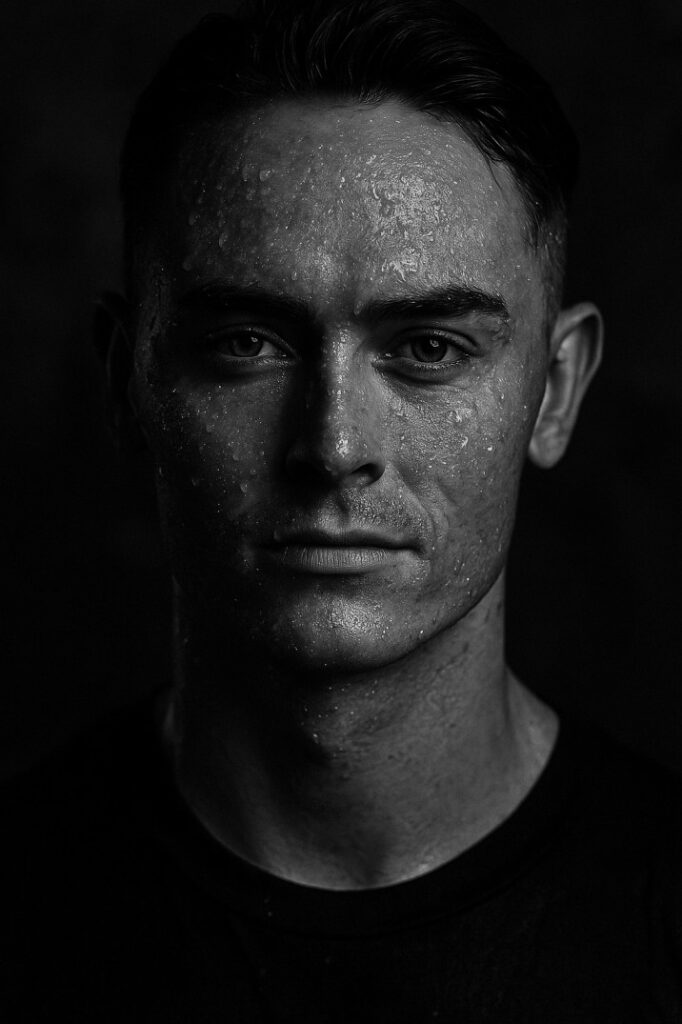

To prepare for the new season of HBO’s Euphoria, in which he plays an amoral high school quarterback, Elordi, 24, headed to a gym he prefers not to name, an exclusive luxury ab bunker in Los Angeles popular among YouTubers, TikTok teens and other wretches of the hype milieu who, invariably, train shirtless.

“I would never train shirtless,” Elordi says, “but from day dot, I would just rip my shirt off and have, like, headphones on, playing Rage Against the Machine. I was trying to understand this mentality of what it is to be in the gym and look at yourself in the mirror and be like, ‘Faaaack, I look good’.”

This is not Elordi’s typical vibe. When we meet at a Blue Bottle Coffee in Malibu, he seems to be trying very hard not to be seen. He’s tied an expensive-looking floral scarf around the lower half of his face, and he is wearing large black sunglasses. His pants and jacket are loose and Carhartt-y. Between his height – he’s six-foot-five (195cm) – his partly obscured face and his baggy clothes, he gives the impression of several children stacked on one another’s shoulders, disguised as a grown man. It is immediately clear to all in this cafe that he is an incognito famous person.

The Malibuans who do recognise him, by his thick brows, maybe, would likely be surprised that he does not often think, Faaaack, I look good – that Jacob Elordi is not as obsessed with Jacob Elordi’s body as everyone else is.

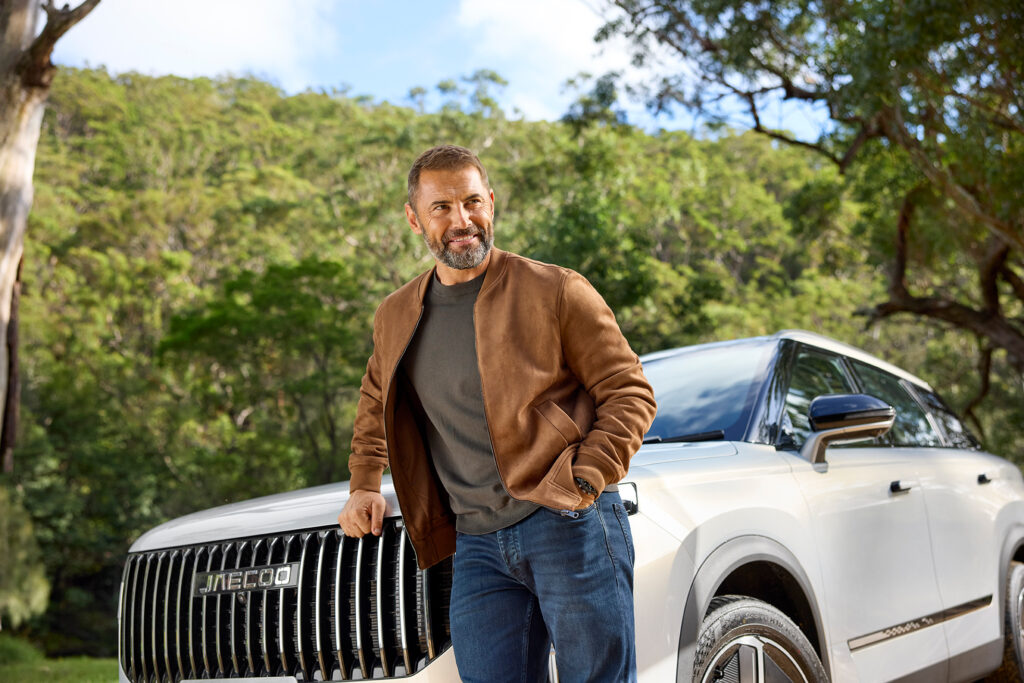

Image: Beau Grealy.

Right now he’s more preoccupied with being noticed for something besides his pecs, his height, his out-of-this-world jawline and his dating life. He’d like to be noticed for his work, for instance. Beyond starring in Euphoria’s second season, premiering on January 9, Elordi will appear alongside

Ben Affleck and Ana de Armas in Deep Water (streaming on Amazon Prime from January 14), a film based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith and coadapted by Euphoria’s Sam Levinson.

But Elordi gets it: he stands out. He towers over everyone in Blue Bottle. He’s especially tall for the film industry, in which actors are often much shorter than they appear onscreen – a holdover from when leading ladies and leading men had to be close in height, Elordi speculates. He is tall enough that petite costars sometimes need to stand on a box to be squarely in the shot or he must split his legs into a V to mitigate the vertical differential.

Everybody has something to say about Elordi’s height. When his mother urged him to try modeling when he was 15, he was told he was too tall for the sample sizes. (“I’m very grateful,” he says of his aborted modelling career. “I truly think I would’ve been miserable if I had to do that.”)

He’s been told he’s too tall to be an actor, too. But how, he asks, does height affect someone’s empathy or emotional availability? “I guess tall people don’t experience things,” he jokes. One could make the argument that they don’t – that, per the memes, a tall man occupies such a privileged position, à la Jon Hamm in the hot-guy bubble on 30 Rock, that his empathy is limited. But one does not make this argument to Jacob Elordi at this time.

Besides, he explains, he’s not actually that tall. “The trick is they just always cast me with girls who are five-foot-two (157cm). Everyone’s like, ‘You’re so big!’ Yeah, but they’re also not big, not even average-sized women. They’re quite small.”

Indeed, in several scenes in Netflix’s The Kissing Booth, now a three-part franchise, Elordi’s co-star Joey King is barely level with his torso, craning her head to speak to him. And Euphoria deploys Elordi’s height strategically: in many scenes, his character, Nate, looms over his on-and-off girlfriend Maddy, sometimes protectively and sometimes threateningly.

On Euphoria, Elordi’s body becomes a dark symbol of a young man’s inner turmoil – over the pressure to be strong and stoic, even sociopathic; over his attractions; over his dad’s porn collection. His character is the epitome of white-male privilege. He lives in an imagined honour culture, weaponising his strength and untouchability. He does a lot of pull-ups.

Nate’s more brutal moments are accompanied by a moody track by the rapper Labrinth. His theme song, “Nate Growing Up”, has a thumping beat punctuated by a pained, primal male “Uaaahhh!” Elordi has the song on his phone and plays it when he’s working to get in the lunatic-arsehole spirit.

Before I watched it, Euphoria was described to me as “dark Degrassi”. In the first season, Nate chokes Maddy, severely bruising her neck. When her parents learn of the assault and move to press charges, Nate creates a web of manipulation: he convinces her to say another man choked her, he intimidates that man into confessing to the crime and he blackmails a character into claiming she witnessed the other man committing the assault. Uaaahhh!

It’s a brave performance for an actor who is relatively new on the scene, in part because Nate is so hateable. (Elordi, for what it’s worth, thinks we throw around the word brave too liberally, especially when it pertains to celebrities taking risks from the safe perch of being a celebrity – he has an idea for a film that plays with that notion, but he won’t share it on the record.) His behaviour in season one inspired think pieces and Twitter rage: Nate was a totem for very, very toxic masculinity.

But at least people weren’t just talking about Elordi’s body anymore.

The other customers in line for coffee seem more interested in the guard dog at Elordi’s feet, Layla. Before anyone can stare at the actor too long, Layla peers up with her warm eyes and the moment is over, the potential interloper distracted. Layla is 10 months old and she is one of those golden retrievers – the runt of a friend’s litter, Elordi says – who appear to be smiling at all times. She is sweet and soft and good and she goes everywhere with him. She guards Elordi in the metaphorical sense, absorbing attention and giving him something to talk about and fidget with.

At the register, Elordi orders an oat-milk latte. The cashier rings him up and then peers at Layla. “I have to ask: that’s a service dog, right?”

Tank by Calvin Klein; sweatpants by Russell Athletic; sneakers by Salomon. Image: Beau Grealy.

“She is,” Elordi answers pleasantly. Layla, who is wearing a utilitarian-style harness that could reasonably mark a service dog in training, gazes up at Elordi adoringly. “Great,” the cashier says, looking relieved.

When Elordi has taken a seat outside at a stone table, I ask him whether Layla is actually a service dog. “Yeah,” he says, but then qualifies: well, he’s done the service-dog paperwork. “She makes me happy, which is a service.” Layla curls up on the ground, unaware that she is living in sin. Elordi removes his face covering – pow, that sharp jaw! – but leaves his sunglasses on, even though it’s late afternoon and the sun, which hasn’t been particularly bright anyway thanks to a robust mist, is setting.

He starts our conversation sitting rigidly. Sometimes he looks down at the table’s chessboard surface, but mostly he stares straight ahead, his gaze unnerving through the dark sunglasses, unreadable, like an FBI agent’s.

But soon he begins to move more. He leans in and out, hunching over and twisting to the right, peering at me with his left eye. He says he typically gesticulates and fidgets a lot in conversation, so I take it as a good sign. Soon he takes off his shades and appears friendlier.

The shyness is endearing, and a little unexpected from someone so Abercrombie looking. The attention on his body – which was full-on after The Kissing Booth, for which he trained twice a day, seven days a week – has unsettled him. The movie features a scene where a foam football bounces satisfyingly off his taut biceps like a grape off a firm mattress. “You learn quickly that what people take away from those movies is your stature and your figure,” he says. “You have all sorts of aged people around the world only talking about what you look like.”

Women might eye-roll at a man apparently discovering global objectification and Elordi’s fandom may be more benign than the kind experienced by female actors, but there are also fewer structures in place to insulate young men from that attention. Whereas sensitivity in how we talk about and write about women is on the rise, objectification of men is often met with a “Must be nice!” dismissal. “I don’t think it’s really a conversation that people have in regards to men,” Elordi says. “It doesn’t keep me up at night, but it’s definitely frustrating. You’ll go to a shoot and you’ll be getting changed or something, and someone’s like, ‘Oooaaah, would you look?’ Can you imagine if I said to a woman, ‘Daaaaamn, look at your waist!’? Like, see you later. I would never do that, but I think people see it on their screens, so they think it’s okay.”

Vintage tank, available at the Society Archive; sweatpants by True Classic; sneakers

by Salomon; socks by Nike. This page: T-shirt by Hiro Clark; sweatpants by Cotton Citizen; sneakers by Salomon; socks by Nike. Image: Beau Grealy.

His is not a serious grievance, he undercuts, but he’s concerned about how the focus on his body might influence audiences’ perception of him. And he’s worried about how it could affect his self-perception. “It’s a slippery slope to put all your value into the vanity of what your body looks like,” he says. “Your body is going to deteriorate.”

Elordi’s may deteriorate less. Objectification was an unsavoury by-product of his training for The Kissing Booth, but he enjoyed the training itself. His mother used to be a personal trainer – he grew up in a “very, very fit family” in Brisbane before moving to Melbourne – and he was an athlete in high school, so exercising and eating well have always been big priorities. And when he’s not motivated by aesthetics, like when he’s training for a role, he exercises because he wants to feel good, now and when he’s 80 years old.

Elordi seems preoccupied with not being too inextricably tied to his fitness, and with the perceived binary between being really fit and being a serious creator. His ambitions suggest that he’s much better aligned with Deep Water than, say, The Kissing Booth – more Ben Mendelsohn than Chris Hemsworth. (The Aussie actor he really looks up to, though, is Margot Robbie. Outside of her work, he says admiringly, “you don’t hear much about her”.)

His role in Euphoria, too, suits him, even if neither the HBO series nor The Kissing Booth was true to Elordi’s own high school experience. This is partly because, he explains, Australian schools look very different from American ones. “They feel kind of communist here or something. There’s barbed-wire fences and, like, lockers. Ours are much more like a community.”

Elordi also wasn’t a sociopath in high school, so when he’s acting on Euphoria, he typically just does the opposite of what he would have done as a teenager. But he did go to a “pretty insane” private all-boys Catholic school in a wealthy part of Melbourne, he says, “and that was not sort of like my position in the world, but it was definitely an eye-opening experience.”

Bottom left: Vintage tank, available at the Society Archive; sweatpants by True Classic. Image: Beau Grealy.

Elordi pauses often during our conversation, peppering his sentences with cool-guy ums and likes. Yet when he begins to describe the culture of the school, his syntax falls apart completely. “Um, looking back at some of the . . . that happens there, it’s like, absolutely not like, uh, they say that, you know, to build young men . . . Um, but no, I don’t think that the structure of that school did anything for building young men at all.”

There were no girls to balance out the vibe, either, Elordi says, apart from at dances with a sister school. He has three sisters, and he’s very close to his mother (“I have a brother and a dad as well, but I grew up in a house of women, you know?”), so he sometimes felt like an outsider in conversations with his classmates. “Seeing the way they spoke about things at the school, I was like, ‘This doesn’t make any sense. How could you speak like that?’”

He further attributes the school’s culture to its emphasis on athletics, pointing to a “win-or-lose mentality” and a bigger-better-stronger mindset. But Elordi was cut loose from the glory of manly sport by a twist of fate – and bone.

He played rugby throughout high school, and he was pretty good at it – right up until the day he went in for a tackle and collapsed on the ground. He’d broken a bone in his back. He had to lie on the floor during school for a year and still feels the injury every day, but he’s glad it happened regardless.

He had arrived at a crossroads: he knew he wanted to be an actor, but in such a sports-driven environment, he felt pressure to focus on athletics. “I was at a point where I wasn’t enjoying playing sports anymore and it let me just be like” – he shrugs – “and just fade away, onto the stage. Which was really, really rewarding.”

Many Aussie actors now popular in the US have salmon-swum up Australia’s soap-opera pipeline, scoring roles on Home and Away (Chris Hemsworth, Isla Fisher, Heath Ledger) and Neighbours (Margot Robbie, Liam Hemsworth, Russell Crowe). Elordi auditioned many times for both shows but was never cast. “I dunno, I wasn’t very good,” he says, laughing. “I was pretty bad.”

He went to acting school in Melbourne and got better, then burst from the Hollywood womb with an ease and alacrity suggestive of someone with a Hollywood-adjacent producer relative, which, as far as I know, he does not have. Now here he is, an ocean away from home.

When it’s almost dark and Elordi seems to have relaxed, I risk asking a question that alludes to his relationship with Kaia Gerber, which, according to scores of news outlets, ended shortly after our meeting. I wonder whether the attention he received when spotted with her was more overwhelming. Elordi straightens up from the table, slackening his face and deadening his eyes, looking away before saying anything. (Uaaahhh!) He answers the question politely, but he speaks coolly – I’ve pried/overstepped/intruded.

“She handles herself wonderfully publicly,” he says of Gerber, “and I’ve learned so much from her about how to handle it, how to deal with it and just kind of be whatever about it, you know?”

Tank by Hanes; shorts by Hiro Clark; sneakers by Salomon; socks by Nike. Image: Beau Grealy.

“Handling it” is relative when you’re the sort of actor who attracts tabloid clicks and, often, acerbic speculation about your relationships. In September 2020, for instance, a Twitter user shared three photos of Elordi with three different women – Joey King, Zendaya, and Gerber – at the same outdoor market. Ultimately, in a response to the national outburst, he shared a photo of himself video-chatting with his parents on Instagram.

“This is a reminder that I am a human being,” Elordi wrote.

But generally Elordi just blinders himself and tries to ignore the attention. Layla, beyond providing the joy a puppy inherently does, seems to help him engage with his surroundings while still keeping himself at a remove. A little boy wearing cool blue elastic-band kid glasses passes by several times on his tricycle, hoping to get her attention. The actress Jennifer Coolidge, or a strong look-alike, emerges from a nearby carpark and drifts by, looking warmly at the dog. Elordi leans down and pets Layla absently. “I just want to be a part of the world,” he says. “I want to have a life. I want to have the same 80-, 85-year – more or less – experience that everyone has. I don’t want to miss anything

by sitting on some overly sour pile of candy.”

Elordi is suspicious of his fandom, in part because of the militant humility Australia enforces on its citizens. It’s “tall-poppy syndrome,” he says. You can be successful, but you shouldn’t be too successful or do too much to put yourself in the public eye.

“The principle of it is nice,” he says. “It helps me check myself a lot of the time and make sure that my head is not, you know, the size of an air balloon. But at the same time, sometimes it can be quite crippling, because you don’t want to accept any of the praise or good things that come from the work.”

COVID has made it difficult for Elordi to return home to visit his family. He speaks to his mother often, pretty much whenever he’s driving, but he wishes he could visit on weekends at least.

He moved to America when he was 19 and he barely knew anybody. “It’s kind of stayed that way,” he says, five years later. “I know a few people. I have a few friends. But I’m not mad about it. I’m here to work, and then I’ll get home when I can.”

You have to do those first few years in Los Angeles, he continues, when you don’t have much money or a real home and you’re still finding your footing. Not that he’s complaining, he adds, because he’s had a lot of fun: “Some people work for decades trying to crack it, so I’m definitely aware, definitely grateful, for the luck that I’ve had.”

Our formal interview over, we walk to the carpark, Layla coquettishly waits to be hoisted into the back of his black Range Rover, where she instantly curls up on a blanket.

As he pulls out of the carpark, his mother calls him on Bluetooth – he promises to call her back. As he drives, he leans back in his seat. When he misses an exit, he exclaims, “Damn, missed the turn-off!” But he doesn’t seem overly stressed about it. There’s an Australianism that Elordi particularly likes: She’ll be right, mate.I ask him to use it in a sentence. He demonstrates with dialogue.

“Oh, how are you feeling?”

“I’m upset.”

“Ah, she’ll be right, mate.”

He whooshes down the Pacific Coast Highway toward the city he currently calls home, the ocean dark beyond the road.

He’s young and talented and he’s figuring it out. She’ll be right, mate.