Unless you’re the owner of a Carrollian-grade imagination, you’d struggle to picture Matt Nable in a romcom. Could you see him as the Owen Wilson character in Wedding Crashers? Or the Hugh Grant character in Notting Hill? Broad comedy, as far as we know, isn’t Nable’s bag. But you know what is, right? Menace. Suppressed rage. Melancholy. Dark secrets. Desperation. Few actors can nail those as believably and seemingly effortlessly as this guy does.

Take his turn in the new Australian film Transfusion (out 5 January in cinemas and streaming on Stan from 20 January), in which he plays Johnny, a former SAS soldier who’s slid into the criminal underworld and sets about dragging his mate Ryan (Sam Worthington) in with him. Nable’s performance amounts to a 106-min. nervous breakdown.

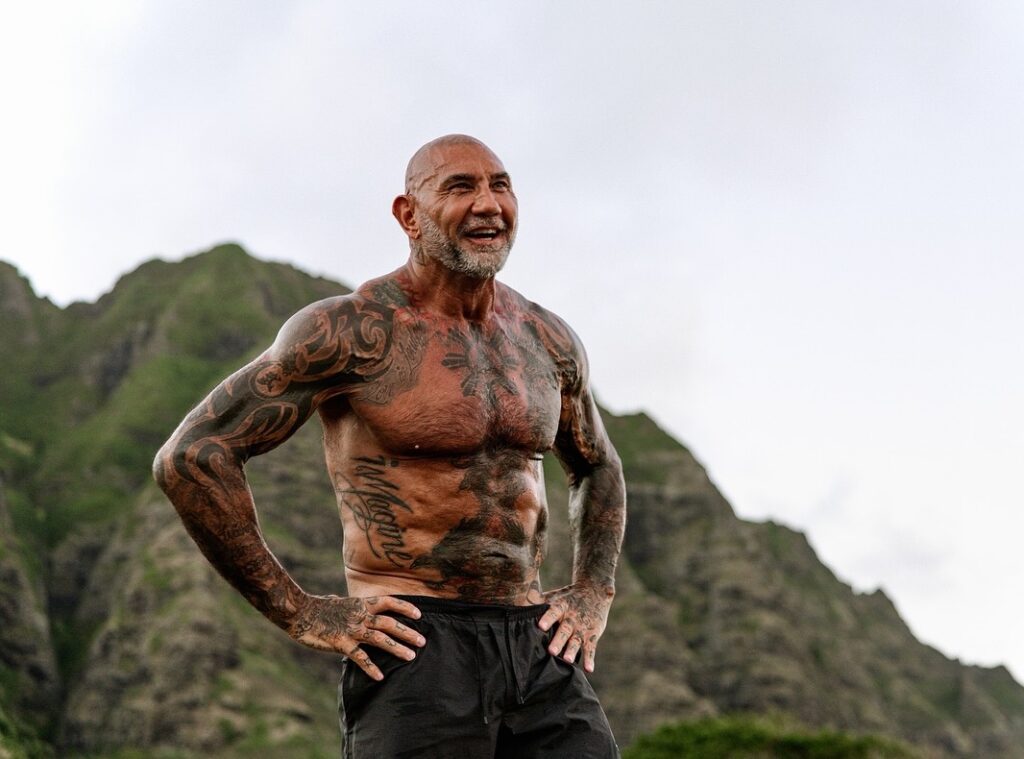

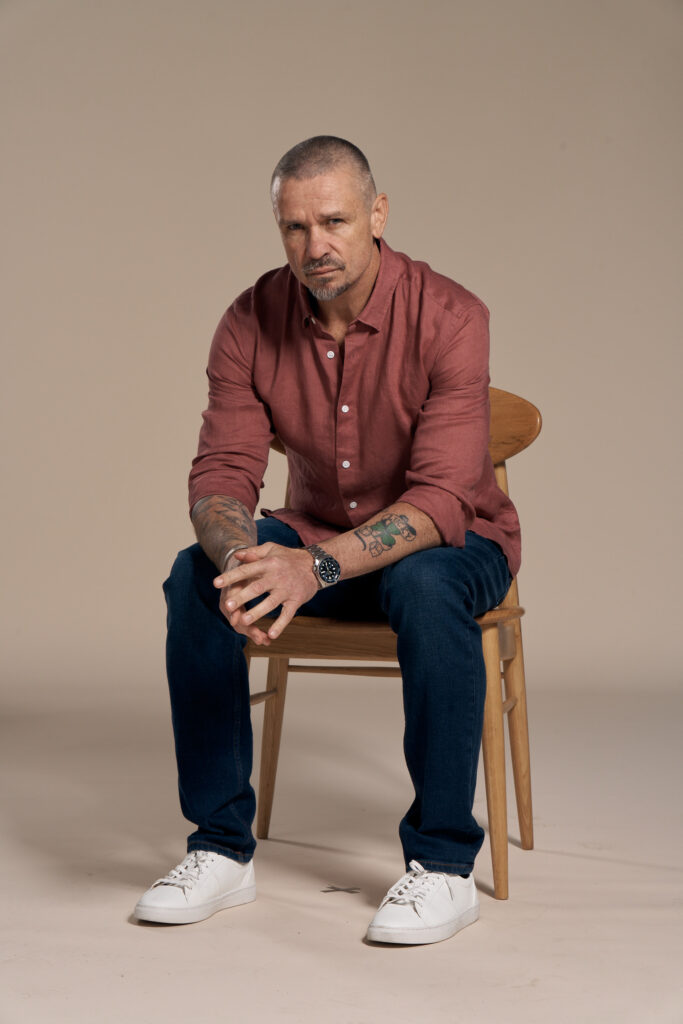

Now, in real time, there on my computer screen, is Nable’s square-jawed, ruggedly handsome face. He’s doing the rounds promoting Transfusion, which he also wrote and directed, and while he looks every bit the bloke you wouldn’t mess with – unsmiling, beefy, tattooed – his tone is friendly, almost gentle, to the point where I feel I can tell him that I didn’t much care for his character of Johnny.

“Look,” he says, “as an actor, you don’t have to like the characters you play; you just have to understand them.” He goes on to say that he understood Johnny very well, that he’s known many a returned serviceman who’s felt marginalised and emasculated by society. “I didn’t dislike Johnny either,” he adds. “Johnny is a good guy… if you’re in his circle.”

Better than most, Nable understands pain. It’s written on his face in his every role and every public appearance. In

the creative ranks, there are few more intriguing figures than this emerging auteur, who devoted his younger years

to rugby league and boxing before realising that what he truly wanted to do was tell stories. With guidance from a Booker Prize-winning novelist, he pulled off one of the more remarkable career transitions, trading scrums and jabs for similes and juxtapositions and never looking back – the writing leading him into acting, the acting into directing. His body of work amounts to a sophisticated examination of masculinity.

“It fascinates me,” Nable says, “because with every piece of masculinity that’s layered over a man, there’s a weakness or vulnerability that lies beneath it.”

The tools for reinvention

In Transfusion, Worthington’s character has a job he detests as a sales rep for an alcohol company – a case of write-what-you-know for Nable, who held the same position in his early thirties when he took a fresh look at a manuscript he’d written years earlier about an ageing footballer who isn’t coping with a changing game and looming retirement. Gee, he thought, this reads okay. But does it? Really? He needed an expert opinion.

Former Manly Sea Eagles teammate Tony Mestrov put Nable in touch with one of the club’s most avid supporters, Schindler’s Ark author Thomas Keneally, who happens to be a kind and generous man as well as a literary titan. Keneally was only too pleased to cast an eye over Nable’s work.

“This is good,” he told him. “If you’ve got this in you, put it away and keep writing.”

Gratified, Nable wrote something else that found its way onto Keneally’s desk. I can’t say for sure what it was, and it doesn’t really matter, but it might have been an early draft of We Don’t Live Here Anymore, the first of Nable’s four published novels. A few months after getting it, Keneally was back on the phone to Nable.

“I’ve just read your new manuscript,” he said. “Son, this is what you should be doing – and I wouldn’t tell you that if I didn’t believe it, because that would be immoral of me.” Nable quit his job that same week and resolved to concentrate on writing for a year. Backgrounding his decision was a key medical fact: Nable has bipolar disorder and, at the time, was experiencing manic episodes that were stoking the tell-tale feelings of uber-confidence and euphoria. In a way, he says now, he might have “got lucky”, because the mania stopped him from listening to well-meant, conservative advice.

Nable made judicious use of those next 12 months, turning his novel about the gnarled footballer into a screenplay that became The Final Winter, which was made on a shoestring and released in 2007 to critical praise. Nable had stepped into the lead role of Grub Henderson, exuding a mix of belligerence, sullenness and an odd kind of decency that would become his métier. In the 15 years since, big-and-small-screen acting work has been a constant, including roles in Killer Elite, Riddick, Hacksaw Ridge, The Dry, Underbelly: Badness, Mr Inbetween and last year’s

The Twelve.

In The Twelve, Nable is a tormented, duplicitous father whose daughter is missing, presumed dead, and he undergoes a rigorous cross-examination from an in-form Sam Neill. Does Nable still find himself learning about the craft of acting when around masters? “Yeah, every day, I’m always picking up [ideas],” he says, citing a recent crossing of paths with Marta Dusseldorp. “Look, I’m at an age now where I know what works for me, but you can always learn, you can always strive to be better. There are intangibles in acting

– stuff you can’t train for – so learning off those people…” Nable trails off for a second or two, then returns with an admission: “Look, I still go on set some days thinking someone’s going to realise that I don’t know what I’m doing”.

He has fewer doubts about his writing. Behind him are those four novels as well as a stack of work for Fox League as a kind of working-class poet. Meanwhile, he made his directorial debut with Transfusion. You could say Matt Nable’s stuff isn’t your cup of tea, but you couldn’t fairly claim he’s not prolific. And it all started with that chat with Keneally.

“Without him, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing,” Nable says. “There’s no reality without that phone call. Tommy’s been a wonderful supporter and a great mentor in many ways.”

Rethinking manhood

If you want to understand Nable, you need to get him talking about masculinity. It’s a theme that pervades almost everything he touches. A lot of his characters drip machismo, but what, to him, does it mean to be a man?

“Look, I’m the father of three kids [two sons, 18 and 16, and a daughter, 12, at time of writing] and I’ve been married for 23 years,” he says. “For me, being a man is making sure the people around me feel loved, and that it’s done in a gentle manner. I was certainly always loved by my mother and father, but there were ways my father fathered that I won’t do, and there’ll probably be ways I’ve fathered that my children won’t do.

“I have a physicality about me – that’s a part of me that I’ve taken from my father. I’m certainly a masculine human being. But I think being a man is a lot more than that. Compassion and understanding and the ability to recognise your vulnerabilities and share those with the people who matter is as important as being the protector. There’s got to be both for it to work properly.”

“For me, there are five things that really matter. Beyond that, it’s fucking bullshit.”

I ask him whether he’s steered his sons into contact sports – whether he thinks that’s what boys should do en route to manhood. As it happens, they are playing rugby league, but not at his insistence, and he’s never coached them or yelled at them from the sideline. “They’ve gravitated to that because it’s part of who they are… they have my DNA,” says Nable. Though he says he’s concerned about what damage his years in league and boxing might have done to his brain, you don’t sense he’s living with regrets. “I enjoyed the physicality of rugby league, and I loved the competition of boxing,” he says. “I never felt fear – and you shouldn’t when you’re apt at something. Courage is relative. The more you get good at something, the less courage is required to do it.”

For guys who think and feel as intensely as Nable does, just facing the world every morning takes courage, the more so when you’re bipolar and the flip side of those manic periods, crushing depression, descends.

Nable has spoken before about his tattoos, which include a date – December 2012 – that represents “rock bottom”. His bipolar strategy has been to ride the highs and survive the lows. Another of his tats is a Hemingway quote: The world breaks everyone and then some are strong in the broken places.

Born warrior

Nable has been exposed to masculine tropes since first opening his eyes, in 1972. His father, Dave, was a PT instructor in the Australian Army – “a very masculine and serious guy and a really good pro fighter”. One of four boys among five kids, Nable found the surest route to paternal approval was to live and play tough. “We grew up very physical, in and around violence at different stages, and I understand that world really well,” he says.

Nable played league from boyhood and played it well, advancing to first grade at Manly and later South Sydney in the first half of the 1990s – a golden (Tina Turner-plated) era for the game when his old man happened to be Manly’s hard-as-nails trainer.

For most guys who make it that far, footy becomes their raison d’être. But it wasn’t like that for Nable. “What I really wanted to do was write,” he says. “You gravitate towards the things you’re good at early on because you get encouragement. I was a good student at school, really good at anything where you had to write stories or essays, and writing was where I wanted to head.”

You get the sense Nable has been hearing for years what a rare breed he is: such a physical bloke, such an imposing presence, yet possessing these artistic gifts more commonly associated with pencil-necked, temperamental types like your reporter. While that might be a plunge into crass stereotyping, it’s not complete claptrap. “There’s a perception that because you played a brutal sport or engaged in a combat sport, it’s easy to disassociate one talent from the other because they’re at different ends of the spectrum,” Nable allows. “But writing was always there for me.”

On leaving school, he figured that if he wanted to write for a living, he’d need to become a journalist. Though that didn’t happen, he kept writing as footy took him to the UK, where he penned what would become

The Final Winter. Rugby league, he says, “spat me out” at 25, after which he boxed until he was 31. “Then you’ve got a big part of your life left to work out what you want to do.”

The deep end

Nable says he’s proud of Transfusion, that “tonally” it came up just as he’d imagined. And the move to the director’s chair? Smooth, he reports. That said, there were times when people asked him questions that he had no clue how to answer, less around the acting than the design and cinematography – stuff he hadn’t had to think about until then, stuff that he’d blocked out as a specialist actor so he could focus on his job.

Here’s a sample exchange about colour palettes with director of photography Shelley Farthing-Dawe.

Farthing-Dawe: What do you want?

Nable: I don’t know.

“But I never felt out of my depth,” Nable clarifies. “I needed help in certain areas, but there wouldn’t be too many filmmakers on their first film as director who have all that covered.” He began the project with some well-considered ideas on the keys to effective directorship. It all starts with casting – getting the right people on board. “And then you give them space so they feel comfortable,” says Nable, who was happy to indulge Worthington’s preference to eschew rehearsal. Nable wanted his actors to know that he’d keep reshooting scenes until everyone was satisfied.

“Sam’s been on some massive film sets where he’s been the lead, so he’s very confident about where he’s pitching a scene and what he’s doing,” Nable says. “And from my perspective, being an actor and coming into the fold as director, you understand what’s going to feel comfortable and what lends itself to a good experience. We had a bit of a mantra on set to be ‘calm and kind’. If everyone was calm and kind, we’d end up having a good day. We were making a film – we weren’t opening anyone’s chest to do heart surgery.”

The allusion here to perspective isn’t random. Nable is in the middle of a family crisis centred on his youngest brother, Aaron, who recently received a diagnosis of motor neurone disease (MND), a vicious death sentence of a malady. Aaron has a small role in Transfusion, and Nable is still trying to comprehend how, 18 months ago, his brother was filming action sequences and now can’t speak. Rather than avoid the issue, Nable wants to talk about it. He puts it squarely on the agenda.

Everything about MND and Aaron’s case is grim. There are seven types of MND, and Aaron has a particularly nasty type – bulbar onset – which starts with slurring of speech, progresses to muscle wastage and breathing trouble, and finishes (typically inside two years) with death.

“He’s got three kids – nine, two and one,” says Nable. “Look, it’s a very cruel disease. But for me, we’re just trying to give him things to look forward to, and while he’s here… not eulogise him, but celebrate him.” Aaron has a tattoo that says “Tomorrow is guaranteed to nobody” – and the truth of those words has resonated with Nable, who will talk to you about his writing and his acting and his thoughts on things, but all of this is against a backdrop of sadness and a belief that little or none of it amounts to a hill o’ beans.

“We’re all here for a short period of time, and while we’re here, it matters to be kind, it matters to the people that you love to treat them kindly, because in the end no one’s going to care what I wrote or what film I was in; the only indication of who I was as a person will be how I treated people… and you get that back tenfold,” he says.

“For me, there are five things that really matter [and they all fall under] relationships: son, brother, husband, friend, father. Beyond that, it’s fucking bullshit. It’s all just fluff. Just none of it matters. Money, career… it’s all just bullshit. We’re not here long enough to indulge in that stuff. What matters are your relationships.”

After a speech like that, where do you go with a man? The answer is nowhere. You’re done. You thank him. Say goodbye. And take a long, hard look at yourself.