Your reflection can be lonely. It shouldn’t be that way, especially not for a kid. Yet if you watch enough screens, whether phones or laptops or TVs, at some point you start to believe those screens reflect the world. And if you never see anyone who looks like you reflected back on those screens, you just might question how you fit into that world. You start to believe that the infinite possibilities you see onscreen aren’t for you.

“I was asked to present at the AACTA Awards, the Australian Academy Awards, and not only was the pronunciation of my name completely butchered, but I was also incorrectly identified as ‘a Hong Kong acting legend’, when in fact I’d never been to Hong Kong.”

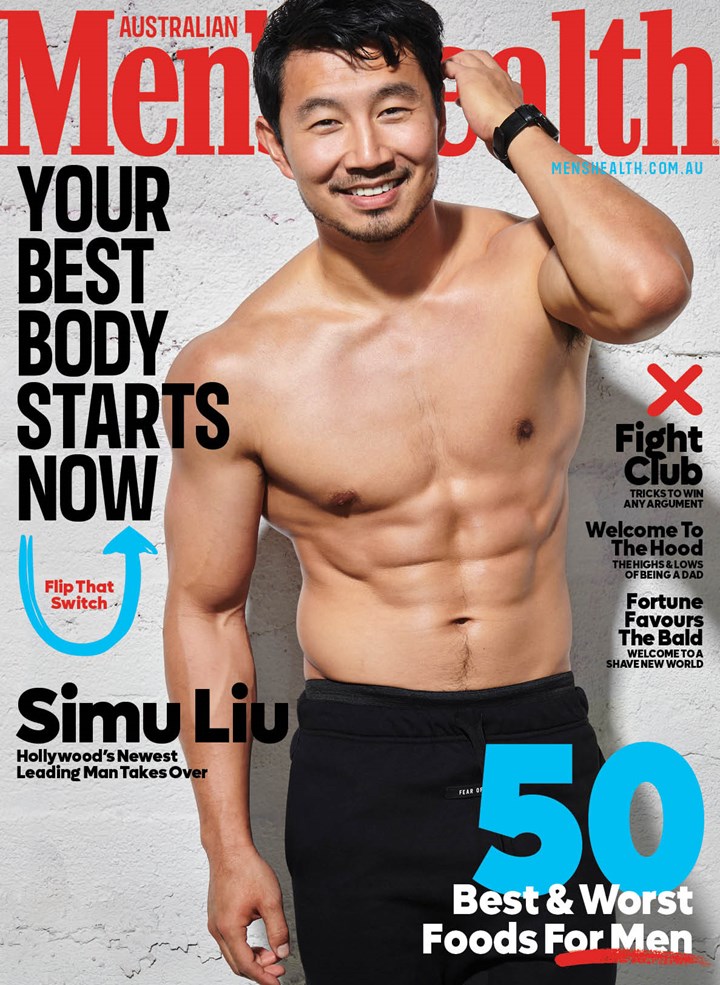

This is what it’s like to be “other” – and it sucks. And Simu Liu knows

this feeling well. We’re speaking about it right now in a Zoom interview while he’s sitting in his Los Angeles hotel room. Liu is clad in a slightly baggy long-sleeved tee that hides a chiselled physique, and he’s sipping boba tea, a decidedly Asian-American blend of green or black tea, milk and tapioca pearls. “I had to get some food in my stomach. Otherwise, you’d be dealing with a very cranky interview subject.”

In September, the 32-year-old will star as the titular character in Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, the first Marvel Cinematic Universe film with an Asian lead. This matters. It comes in the midst of a moment for Asian Americans, who’ve grown more and more conscious of (and vocal about) the racism and lack of representation that have long defined their American experience. It is not a new feeling for many Asian Americans, but it is a new discussion, one with new hope. As the son of a Chinese mother and an Indian father, I understand this intimately. It’s been more than two decades since a New Jersey neighbour, angry at my mum, told her to “go back to where you came from”. I’ve never spoken of it until now, because I believed that somehow my family was at fault – and because I never understood that I could speak about it. “There is something missing in Asian America,” says Liu, who

is Chinese Canadian. “They’re missing people to tell them, ‘It’s okay to be who you are; you belong; just be unapologetically you; you’re not less than anybody else’. ”

Liu’s embrace of equality, identity and authenticity resonates deeply in today’s pop culture, but that’s relatively new. Decades of Hollywood blockbusters, prime-time TV shows and magazine covers have narrowed our view of what a hero looks and acts like, how “strong” and “powerful” and “masculine” come together to throw impossible touchdowns, kiss Halle Berry and save the world from Thanos. Hollywood has grown increasingly aware of these issues of representation, and in the wake of 2018’s Crazy Rich Asians, Asian-American films and TV shows are on the rise.

But an Asian Marvel superhero signifies something else, because of Marvel’s outsized cultural imprint and because superheroes have always represented ideals. Not everyone wants to be Minari’s Jacob Yi, the Korean-American farmer who moves his family cross-country to Arkansas, even though the film won a Golden Globe. But who doesn’t want to be an Avenger, right? Yet for all the diversity in the epic final battle of Avengers: Endgame, there was but one Asian, Wong, Doctor Strange’s . . . sidekick. Shang-Chi changes that. And never mind that the original character himself is a study in Asian representation done wrong, or that the early years of the MCU were straight from the whitewashing playbook, or that you (and nearly every Marvel YouTuber) have been pronouncing his name wrong for months. (The first syllable rhymes with “Kung,” not “Kang.”)

An Asian American is about to save the world – and look jacked doing it. Three years after the late Chadwick Boseman and Black Panther gave the MCU its first Black-led film, a different “other” now gets to be the hero.

“I am that person that struggled with my identity my whole life,” says Liu. “I am that person that’s always felt like he wasn’t enough. And those [experiences] are more core to Shang-Chi’s character than his ability to punch people.”

A Hero Is Born

When Marvel Studios announced Shang-Chi in 2018, Liu uttered the same “WTF” as every other comic-book fan. He remembers staying up late and scouring the Marvel web to learn about the character, and the more he uncovered, the more he grew disenchanted. Instead of raiding the comics for an ultrastrong hero (like Amadeus Cho, the Korean Hulk) or superhero royalty (like Namor, Marvel’s version of Aquaman), Marvel found its first Asian lead in . . . a Bruce Lee clone. Shang-Chi was created in the 1970s because Marvel wanted a version of Lee, and he’s the son of Fu Manchu, perhaps the worst Chinese stereotype. Early stories had him speaking in broken-English phrases. His superpower? Kung fu. “I was almost disappointed,” Liu says. “I was like, how many opportunities do we have for Asian superheroes, and this one guy is, like, just a kung fu master? It just felt kind of reductive and, you know, not true to life and not anything that I could relate to.”

It seemed like another misstep from Marvel, which had repeatedly slighted Asians. Twice in the studio’s first decade, MCU films rewrote iconic Asian characters onscreen, first whitewashing the villainous Mandarin into Ben Kingsley in 2013’s Iron Man 3, then casting Tilda Swinton as the Ancient One in 2016’s Doctor Strange. Swinton’s casting, after 10 years of films with next to no Asian representation, was especially vexing, since the film still placed her character in Nepal, a South Asian country. Marvel initially claimed it had chosen Swinton to prevent the character from fulfilling an Asian stereotype. Fans called bullshit. Five years later, Marvel head Kevin Feige doesn’t argue. “We thought we were being so smart and so cutting-edge,” he told me in a Zoom interview. “We’re not going to do the cliché of the wizened old Asian man. But it was a wake-up call to say, ‘Well, wait a minute, is there any other way to figure it out? Is there any other way to both not fall into the cliché and cast an Asian actor?’ And the answer to that, of course, is yes.”

Since Marvel Studios’ inception, Feige says, the studio has had a binder of “great characters who could make great movies regardless of how famous they were”. Shang-Chi was in that binder, because stereotypes aside, it’s a very Disney story: in the comics, the character discovers his father’s true nature, fakes his own death and runs away. “You break through that and become a hero,” says Feige. “It was always a really, really great story.” Because of the character’s obscurity, Marvel could reinvent Shang-Chi in ways it couldn’t alter Spider-Man or Captain America. The MCU version can (and will) fight, but his new origin story cuts deeper. “It’s about having a foot in both worlds,” says Feige, “in the North American world and in China. And Simu fits that quite well.”

“It’s just very important to be a guy that stands up and says, ‘Hey, this is not okay’”

Longing For More

Fittingly, there’s a superheroic origin story behind Liu’s own journey to Hollywood, especially the way he tells it. He was born in 1989 in Harbin, China, and lived there until he was nearly five. And then one seemingly normal morning . . . “A stranger showed up at the door and was like, ‘Hi, Simu, I’m your dad’, ” he says. “So I had to say goodbye to my grandparents, the only parental figures I’d ever known, and then kind of go to this completely new life in Canada.”

Shortly after Liu was born, his parents immigrated to America but eventually settled in Toronto. The plan: create a life for Liu, then send for him, though they knew it might take several years. Liu’s first name (pronounced SEE-mu) speaks to that separation: it’s from the Chinese characters that mean “introspection” and “envy” or “longing”. “That was them knowing that I would grow up without them and without parents,” he says, “and that I would always be longing for them – and they would always be longing for me.”

That symbolism had evaporated by the time Liu was attending University of Toronto Schools. Toronto has a large Asian population, and Liu says UTS was “65 per cent East Asian”, but he still felt like an outcast in high school. Although he was a natural athlete, he spent most of his Toronto childhood home alone, watching a steady diet of American TV shows like One Tree Hill, The O. C. and Power Rangers, and falling in love with Marvel characters. Whatever Liu watched or read, the hero looked the same. He tried to mimic those personalities, joining the basketball team, which he believed would lead to instant popularity.

But he still didn’t feel accepted. “The main character is always, you know, this blond-haired, blue-eyed guy who’s the high school quarterback

or the star of the basketball team,” Liu says. “That’s all I wanted to be, really, truly. I definitely was not that.”

But it was all he wanted to be. He grew angry at his parents because they hadn’t given him a “white name”, and he briefly evaluated options for a name change (Simon, Steve or Tommy). He fought with his father after parent-teacher conferences revealed shaky grades. At 19, he chased validation by applying to work at Hollister, of all places. “The typical Hollister guy was, like, blond hair, blue eyes, six-pack, whatever. I had the six-pack, but I didn’t have any of the other stuff going on,” he says. “I was like, I want that for me. I can hit that standard of fitness.”

In college, he “compromised” with his parents, who wanted him to end up in a high-paying career, by attending business school and landing an accounting job at Deloitte, in part because it conjured images of slick-dressed men in fast cars. He was let go after less than a year, and he decided to try acting. His parents weren’t pleased. Liu spent the next two years barely speaking to them, his career stuck in neutral. Things started off with slight promise in 2012 when he earned a job as an extra in Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim, which was filmed in Toronto. But after that, he scored only forgettable roles that had him onscreen for just seconds, like his turn as “desk officer” in an episode of the CW’s Nikita. In 2013, he played a character named Yakusa Koto in Bike Cop: Begins and only realised years later that his exaggerated, stilted Japanese accent was furthering the Asian stereotypes that had haunted him throughout high school. Liu had bartered his identity away for a caricature of his identity. “Looking back now,” he says of playing Yakusa, “I wish I could slap myself in the face.”

Unmasked

Liu still dreamed about playing superheroes but had to find other ways to perform. So there he was in 2014, walking into a Toronto apartment wearing a head-to-toe Spider-Man suit. He did a backflip, landing with legs splayed slightly, one hand on the floor. A crowd of 10-year-olds cheered. It was the classic Spider-Man pose, and this was one of his “odd jobs,” a way to pay the bills when he wasn’t earning his TV bit parts. The job: wearing a Spider-Man costume for children’s birthday parties, making a dramatic entrance, then leading them through games here, maybe doing an extra flip there. But this job had a condition: keep the mask on, because once it came off, “the whole believability would be shattered.” The rule had come to epitomise the lack of superhero representation for Asians.

Yet with Shang-Chi, Liu truly has shattered the rule, unbelievably. “That really sets us apart, aside from, of course, it being such a celebration of diversity and Asian-ness and our culture, is that my character does not have

a mask. So there’s really nothing to hide behind.”

The year following his stint as Spider-Man, Liu watched a play called Kim’s Convenience, about a Toronto-area convenience store run by a Korean-Canadian family. Penned by Korean Canadian Ins Choi, it had serious prodigal-son vibes thanks to the relationship between Appa, the Kim patriarch, and Jung, his oldest son. Liu had heard Kim’s would be turned into a TV show, and he wanted to study up. He left the theatre with tears running down his cheeks. “I kind of saw [my parents’] side for the first time,” he says. “It really just hit me how much they sacrificed to come to this new country, to speak a language that they didn’t know at all. It really made me sad for all the years that I spent resenting them.”

Liu eventually won the part of Jung on Kim’s, and the show was an instant Canadian hit that grew a loyal Netflix following. Among Asian-Canadian creatives, Liu finally felt accepted. Playing a role he’d lived proved cathartic. His five seasons on Kim’s, which had its series finale in April, were “therapeutic”, he says. He’s now much closer to his parents and speaks with them regularly.

The more time Liu spent with the cast, and the more he did interviews and public appearances, the more he realised that his own journey to uncover his identity had never needed to be so solitary. Time and again, Asian Americans asked how he mended his relationship with his parents and how he found his way into acting. “Even bogan Aussies were coming up to me like, ‘Hi, we love your show. We see you on Netflix all the time. When’s the new season going to come out?’ They were so enthusiastic, so incredible and that’s totally ethnicity agnostic.”

A generational battle was taking place among Asian Americans, one in which well-intentioned first- and second-generation parents targeted professions like medicine, law and academia for their children. Those professions have little room for subjectivity – and that can mean less chance of prejudice and racism. But the next generation, Liu’s and mine, arrives in an interconnected world that encourages trailblazing. While our parents scrapped to success, we dare to experiment. For Liu, that was acting; for me, Men’s Health’s first Asian-American fitness director, it meant writing and training. Older Asian Americans fear these untested routes because there’s more room for failure, no proof of concept, no guarantee of success. For decades, they were right.

This is changing. From Kim’s to Fresh Off the Boat to Minari, there’s increasing proof that Asians can not just survive but thrive in entertainment. In entering this world, where society crafts its new myths, young Asians are finally able to record their stories and take control of their narratives. “When I think about my parents, they wanted to minimise all of their struggle; they never enjoyed talking about what they went through coming over here,” Liu says. “In a way, those stories will be lost in time if we don’t fight for them, because white people aren’t going to write them for us. So in a lot of ways, I feel like it’s our responsibility to kind of, to document and to expose it, what has been going on in our world and our collective world and communities, and to share that story.”

Liu believes he must shoulder the load of this storytelling. Since his awakening on Kim’s, he’s presented himself as “proudly Asian and unapologetically Asian” on social media and in appearances, talking openly about the stereotypes that lead Asian men to be viewed as weak and unattractive, and, more recently, speaking out about increasing levels of violence against Asians. “We’re experiencing harassment and violence at an unprecedented level,” he says, “and it’s just very important to be a guy that stands up and says, ‘Hey, this is not okay’. And there is a real responsibility that comes with not just anybody with a platform but with mine, specifically, of being the first of a community to be, you know, a superhero.”

You feel the Peter Parker vibes. He knows it, too. “Maybe that’s why I loved superhero movies from the very get-go,” he says. “They grapple with these big ideas of good versus evil. Once you have power, how are you going to use it?”

Answer: superheroically. “Simu is brave,” says actress Awkwafina, who plays a new character, Katy, in Shang-Chi. “Not only in the sense of a superhero but in how he chooses to come through for his community. It was

a very inspiring thing to see. ”

Heroic, To A Tea

This is a story about an Asian superhero, and martial arts play a part in that, but Simu Liu did not earn the role of Shang-Chi with his kung fu skills. He earned it with his acting skills. Liu had only limited martial-arts experience before this film. This is important to Liu, and to everyone on the Shang-Chi team, and it’s critical to the conversation about Liu as an Asian-American leading man.

Liu describes himself as a “self-taught guy who likes to do flips in his backyard” and takes pride in his personal superhero transformation. He added five kilos of muscle to his 180cm frame, bulking up to 84 kilograms. He essentially crushed three-a-day workouts during filming last year in Australia. He’d lift weights and work through fight choreography daily. And every few days, he’d gut out a stretching session to build the flexibility needed for kung fu.

One stretch had him sitting on the floor, straight legs spread wide. A trainer mirrored that position, placed his heels against Liu’s, and gradually pushed the hero’s feet apart, driving him into a near split. He could barely walk after each stretch session, but the work he poured into playing the role serves as proof that he’s an actor, not a martial-arts curiosity. “As with any actor in any role, as Ryan Gosling did when he learned to play the piano for La La Land,” Liu says, “what I think Marvel did, what I hope Marvel did, was they cast an actor.” That was director Destin Daniel Cretton’s aim, and that may be why early audition tapes had Liu and other hopefuls duplicating scenes from Good Will Hunting, not John Wick.

This is not a story about kung fu. Cretton, whose earlier films include The Glass Castle and Just Mercy, calls it a story about “identity”. Shang-Chi will learn that his father is the true Mandarin, a character named Wenwu, who, played by Tony Leung, is being touted as Marvel’s most multidimensional villain. Shang-Chi will have to deal with this while also facing another baddie, Razor Fist (Florian Munteanu), and encountering his sister, Xialing (Meng’er Zhang). But don’t expect the film to start with brawling. “We wanted to show people a character who is distinctly Asian American right off the bat,” says Cretton. “Before you even know anything about his past, his upbringing, his martial-arts skills, we wanted people to know that this is an Asian American.”

This approach allows Cretton, Liu and the rest of the heavily Asian-American team to invigorate the film with an energy and soul beyond the title character’s trope roots. Decades ago, Asian culture was represented in film only by Bruce Lee–inspired combat. In Shang-Chi, brawls stand alongside scenes that illuminate other parts of the Asian-American experience.

Liu holds up his now-empty boba tea, a staple of Asian-American culture, especially in San Francisco. “There are millions of people that consume this drink, like, unhealthy amounts of it,” he says. “It’s such an iconic Asian-American drink that I was like, You cannot make this movie without some sort of boba.” It was a last-minute add to the film, with the logos rush-printed on cups in Australia before shooting wrapped.

In Shang-Chi, kung fu no longer feels like a token touch of inclusion. This is Asian Americans owning their stereotype. “Kung fu for kung fu’s sake, as an aesthetic or a prop, that’s where it starts to get tropey and dangerous,” says Liu. “[But] there’s a reason why when Hong Kong action was introduced to Western audiences, people went bananas for it. Kung fu is, objectively, really cool.” I can’t help smiling as he says this. It’s the reason I’ve never minded the Bruce Lee cracks. It’s why I wouldn’t mind being called Shang-Chi in a few months, when the movie drops and percolates through the culture.

With Great Power…

All of this, to Liu, is progress, and his job (his great responsibility, if you will) is to continue driving towards more progress after Shang-Chi. That means continuing to speak loudly about the Asian-American experience, and continuing to grow his Hollywood profile. And it means thinking carefully about his next projects.

He likely won’t do another kung fu movie soon, because what good would that do? “On the shoulders of all that’s come before me, with Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan and Jet Li, to finally be in an opportunity where we can explore uncharted territory for Asian faces, to then stay in the martial-arts realm, it wouldn’t be a good move,” he says. “I think you’ll see me in something that’s not distinctly Asian. And pretty soon you’re going to start seeing my name pop up in projects I’m not acting in.”

To truly advance Asian-American representation in entertainment, he believes he needs to produce and direct and write, too, creating opportunities for others. He spent his Sydney lockdown (the first one) writing a memoir, set to be published in 2022.

“It’s definitely a time to re-centre,” he says. “I mean, I happen to love what I do. Ultimately, when it’s all said and done, it will be more than just the roles that I took on as an actor. It’ll be what I’m able to contribute to the world in terms of stories, in terms of culture.”

Once you’ve seen yourself as a superhero, the possibilities are endless.

This article originally appeared in the October 2021 issue of Men’s Health.