I was nine when I first thought my dad wished I wasn’t his son.

It was the end of the summer break in 2003. I was chilling at my boxy, white Ikea desk, etching bubble- lettered maxims onto my school folders, when I heard him shriek to my mum: “He wrote ‘beast’ on his school books, Angela. It should say ‘best’. Corey is the beast – what’s wrong with him?”

It turned out I had dyslexia and a truckload of learning disabilities, but those harsh words stayed with me. Sometimes, still, I feel unworthy of his love and respect.

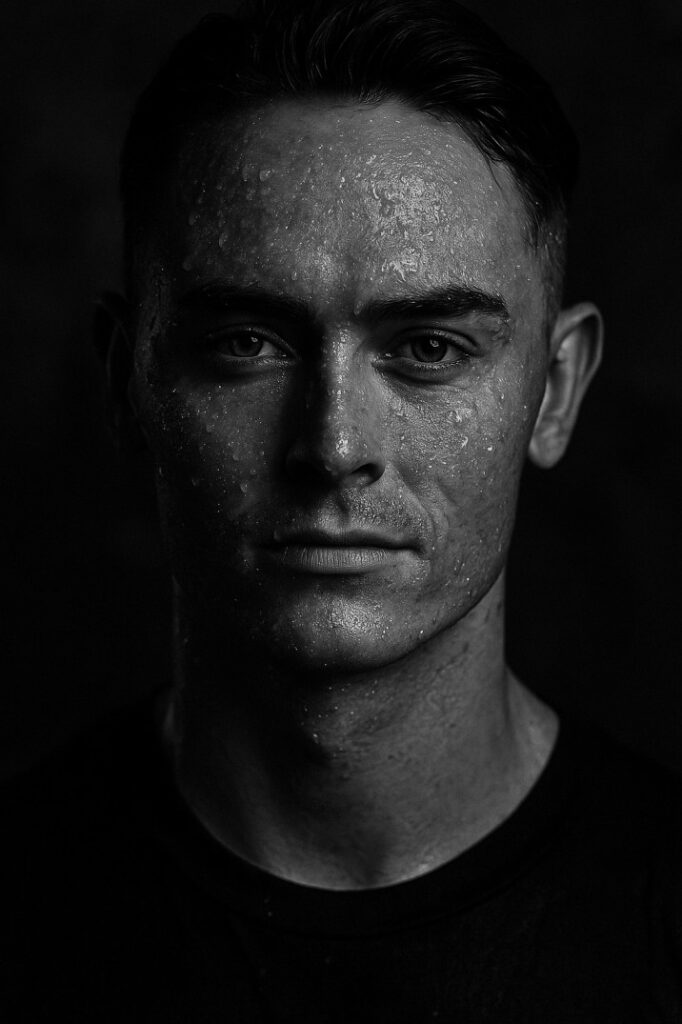

Dim, my dad, is a soft-hearted and compassionate man, with broad shoulders, a buzz-cut and an unshakable demeanour. He combines some of the whimsy of Christopher Moltisanti from The Sopranos, with the intelligence of Walter White from Breaking Bad.

When I was 20, while he holidayed in South America, he funded a stranger’s child’s entire education. But his altruism never mended his proclivity for substances and the neglect that followed when he came home. One such time, when I was in high school, he forgot to pick me up after I’d been away on a purification retreat, leaving me standing alone for two hours on my birthday.

Breaking away

Through my teens, he would harp on the tightness of my skinny jeans: “Dude, can’t you wear jeans a little looser – those aren’t a good look,” he’d say as he blew out clouds of smoke from the cigarette clenched between his two front teeth. My pink, fairy-floss hair and my sanctimonious attitude also grated on him.

I wanted to please him because, well, he was my dad. And at times I felt embarrassed for lacking the characteristics of a “typical” dude, so I never told him what I needed for fear of seeming weak.

Since that humiliating night in 2003, I’d longed to escape the clutches of my Greek and Māori family, often begging to be sent to boarding school or allowed to live in Paris – or some other zany idea I’d concocted from watching too much television.

At 17, I moved out of home to take refuge with monks and nuns at the Tara Institute, a Buddhist monastery. At 23, having moved more times than my mother and father combined, I fled Melbourne for good with $2000 to my name to begin a new life in the Big Apple.

I felt liberated, in control and unashamed.

Constant presence

At last, I no longer had to conceal who I was: a stout-hearted, introverted gay man who’d pursued a careerist and, at times, shambolic lifestyle. I could live my life without worrying about disappointing my old man.

Distance helped our relationship. Before I returned to Melbourne amid the pandemic in October 2020, I’d been emailing him daily, telling him about my troubles at work and my issues with my roommate, as well as confiding in him whenever things went south (which was often). Father and son, separated by a vast ocean, had never been so close.

When I was struggling to find work, worried I didn’t have the cojones to make it in the five boroughs, he bolstered my confidence by reminding me of who I was and how far I’d come. Afterwards, I rode the M-train glowing from the approval I’d yearned for decades ago. I had finally made the man proud.

And yet in the back of my mind, I was convinced he was proud of me only because I’d exceeded his expectations. I imagined him boasting to his mates, gushing about my accomplishments. I was suddenly the trophy son; nothing more.

When I think about my old man, a photograph comes to mind – a polaroid with an ochre-hue, taken in the late 1970s when he was a teenager. He’s holding up a Rubik’s cube between his fingers, mimicking the action of the photographer. I see myself in him – almond eyes, strong jawline, smart-arse streak. I see a boy missing fatherly love, an ill-equipped teen who experienced too much criticism, too soon.

Recently, we argued over a comment he’d made about corporations using the LGBTQIA movement as a ploy to divide and segregate communities. I understood where he was coming from. But, worked up by my brother’s homophobiaand my father’s facetious remarks, I blew up. I told him that, whenever I wanted, I could sever our relationship unless he could start to see my pain.

The truth is, he never will. He can’t. To understand a typical day in my life – abuse on trains and trams just for existing; having straight, strange men yell at me in bathroom bars, ordering me to drop to my knees and pleasure their junk – is beyond him. And I’ve come to realise it’s unfair to expect otherwise.

More often than not, I can’t control the way I react to his criticism. Everything inside me turns sombre, and all those times I felt alone as a teen, struggling to keep afloat, come rushing back.

Tough enough

The beauty in all of this? I love him more than I ever have. How, you might ask? In Tibetan Buddhist philosophy it is taught that even though we may perceive a parent’s actions as negative – say, for instance, hitting a child when they’re in danger – it stems from a place of love and a desire to protect them. I can see now that that is all my father ever wanted to do.

Sometimes, still, I find it hard to tell him exactly what I’m feeling, or why. But after each argument or talk or walk or cigarette we share, I know, deep down, he loves me unconditionally and means no harm.

The greatest gift he has given me – besides his sperm inseminating my mother’s egg to create me – is that his love for me and the awkward, sometimes misguided and occasionally offbeat ways in which he expresses it, has made me into the man I am today, one who, in the face of adversity, can be the strongest pile of sticks for my future husband and kids.