A WORLD FIRST report released today from the Movember Institute of Men’s Health offers an unflinching look at how young men engage with online content about masculinity – a reality many of us have overlooked or misunderstood.

For too long, public discourse has swung between extremes: alarmist panic about radicalisation and dismissive eye-rolling about young men’s online habits. Both miss what’s actually happening. We sought a new tact in this report; to spend time listening to young men, rather than talking at them or around them.

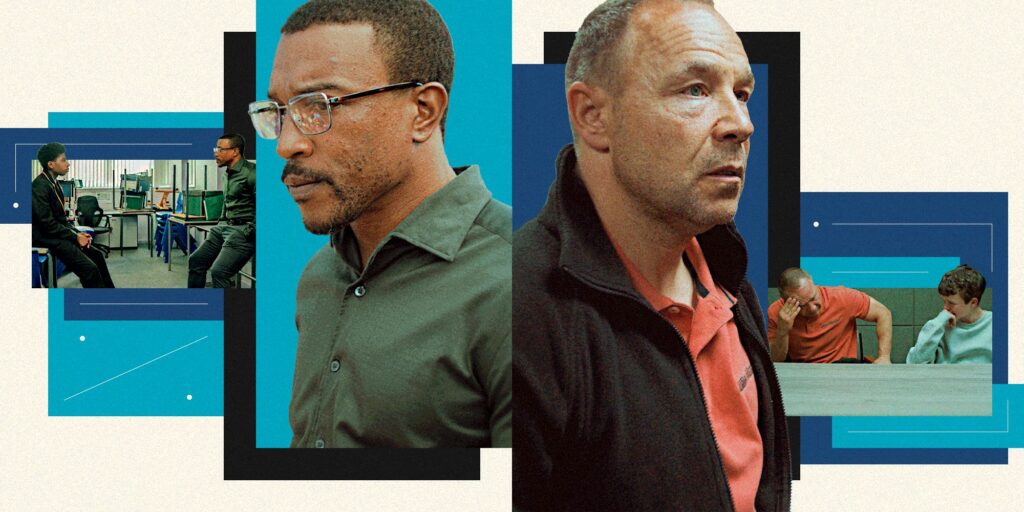

The recent wave of conversation sparked by the TV series, Adolescence, is a prime example of a cultural freight train racing ahead. When you look who’s onboard, you’ll realise pretty quickly there aren’t any young guys joining the conversation.

The findings of Movember’s Young Men’s Health in the Digital World report are clear: nearly two-thirds of the 3000 young men surveyed across Australia, the UK, and US engage regularly with men and masculinity influencers. Notably, we chose not to label this content part of the ‘manosphere’ – an outside-in term that is increasingly outdated and misses the mark when it comes to the reality of young men’s engagement with this content.

It’s no longer some weird subset of fringe communities; these ideas have entered the mainstream, shaping culture and attitudes.

While the most radical ideologies still linger on the margins, their influence seeps into lifestyle content, sometimes cloaked in motivation, self-improvement or entrepreneurial success, giving rise to more socially acceptable – yet still potentially harmful – narratives about masculinity. This shift is largely driven by social media platforms, algorithms, and influencers, which shape young men’s understanding of what it means to be a man today.

Whether intentionally or unintentionally, these forces often blur the lines between radical and moderate perspectives. For many, these messages are woven into everyday life – embedded in the media they consume, the figures they follow, and the groups they engage with.

And here’s what should give us pause: young men watching this content report feeling more optimistic about their futures than those who don’t. As mental health professionals and advocates, we have a choice. We can keep wagging our fingers from a distance, or we can sit alongside young men in the messiness of their developing manhood and understand the appeal of influencers’ content while offering an alternate narrative that still sates their unmet needs.

Young men aren’t stupid. They’re savvy digital consumers seeking something our society has failed to provide: clear guidance on navigating masculinity in a rapidly changing world. The report shows they find these influencers entertaining (45%), motivating (43%), and thought-provoking (41%). Most importantly, 75% reported feeling more motivated after following influencers’ advice, while 58% said they felt happier.

However, in the same breath, our data reveals concerning paradoxes. Despite feeling more optimistic, these same young men also reported higher rates of psychological distress, including over a quarter reporting worthlessness, nervousness, and sadness. They were less likely to prioritise mental health and more likely to engage in risky behaviours, like working out while injured or using potentially harmful and unregulated supplements.

Put simply, they feel better momentarily while potentially harming themselves in the long term.

The deeper issue is not just content – it’s connection. These influencers are offering something young men say they struggle to find, a community that validates their experiences and offers the belonging many desperately crave.

When 76% of young men engaging with this content believe “men who can’t control their emotions are weak”, we’re witnessing a collective coping mechanism, not just toxic ideology. In a world where vulnerability often feels unsafe, traditional masculine stoicism becomes an attractive default.

The content resonates because it speaks directly to common anxieties around dating, fitness, financial success, and identity – the very topics young men tell us they feel unable to discuss openly offline.

Rather than condemning young men’s choices, we should ask: what does this content provide that mainstream mental health support does not? When 62% believe men should solve problems on their own, they’re not rejecting help – they’re expressing alienation from systems that haven’t adequately acknowledged their specific struggles.

The solution isn’t censorship or shame. It’s creating alternative spaces where young men can find the guidance, motivation, and community they’re clearly seeking, without the potential psychological and physical harms currently attached.

Most importantly, it means listening to young men’s actual experiences rather than imposing our assumptions. After two decades of this work listening to guys at Movember, we know young men are actively engaged, not passively indoctrinated. They report trying things, evaluating results, and making choices. Their agency deserves respect.

If we’re serious about supporting young men’s wellbeing, we must meet them where they are, not where we wish they were. That means developing programs that offer clear direction, motivating content, and genuine community without the harmful ideological undercurrents. It means addressing dating frustrations, career anxieties, and identity questions with the same seriousness as these influencers, but with evidence-based approaches that prioritise long-term wellbeing.

The conversation about young men’s mental health needs to move beyond moral panic, which stifles progress toward meaningful engagement. The first step is acknowledging what our research at Movember makes clear: young men are showing us exactly what they need. It’s time we listened.

Related:

Why ‘Adolescence’ is about fathers

A doctor’s own bitter pill to swallow: “I struggle to talk about mental health”