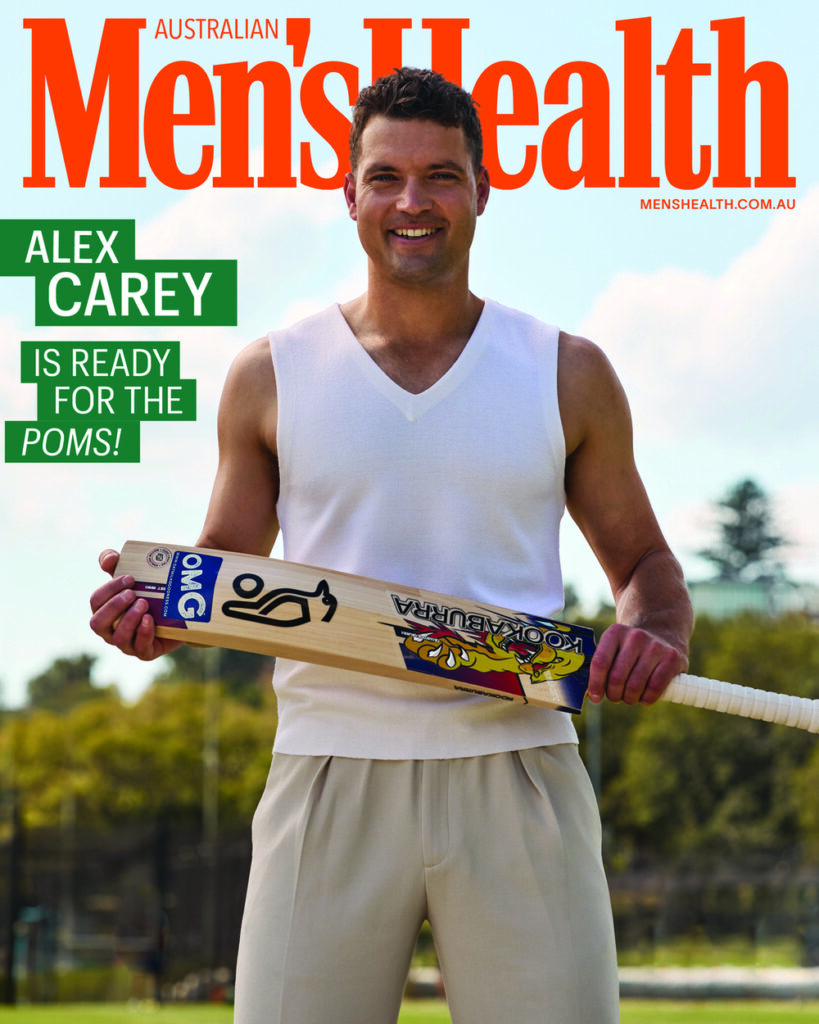

Alex Carey on standing tall when it counts

The Australian wicketkeeper-batsman’s career has been defined by his ability to bounce back from setbacks and keep forging on. Ahead of this summer’s Ashes, he sat down with Men’s Health to discuss mindset, fitness and why he doesn’t mind having a target on his back

BY BEN JHOTY

ALEX CAREY IS causing something of a stir among his teammates, as he poses for the camera on a patch of grass in front of the Matthew Hayden grandstand at the National Cricket Centre in Brisbane.

It’s a gloriously sunny September day in ‘BrisVegas’ and Carey, who’s decked out in some very preppy threads with a sweater vest, looks like he could be at a country club or croquet lawn.

“What is that?” asks a teammate of his flashy garb. “I like it,” Carey responds, smiling, his blue eyes glinting in the sunshine. He looks at our crew. “I think they’re jealous.”

There’s more cat-calling and even some wolf-whistling later, as he emerges from the grandstand’s locker room in a white vest. Twenty-year-old Sam Konstas, who’d earlier told me that Carey is itching to go shirtless for his Men’s Health cover, spots us on the steps of an adjacent grandstand. “Got your shirt off yet?” he yells out.

Carey grins, as he shakes his head, though you get the feeling he’s okay with a bit of ribbing, even from a cheeky young upstart – he’s a good sport, as most self-assured blokes usually are.

Should Carey have his shirt off? It’s not a silly question, given the way the former Aussie Rules player’s arms ripple as he clasps a bat. Perhaps those arms were always meant for jerseys and vests rather than being buried under flannels, as they have been the past 15 odd years.

It’s easy to see Carey as a lithe midfielder, scooping up the footy around centre bounces and delivering precise passes inside 50. It wasn’t to be, of course – he was cut from the fledgling Team GWS back in 2011. But his dream – playing sport for a living – wasn’t quite dead.

“I’ve got a really cool picture of me when I was around the age of five and I was playing backyard cricket at home and I had on a Redbacks South Australian cricket hat, an Aussie One-Day shirt, some football shorts and I was holding a Kookaburra cricket bat and it all sort of worked out,” he tells me, as we chat in the grandstand, a drone buzzing somewhere overhead. “I was able to do all of those things.”

Indeed, he was, but the truth is, while that picture of the young kid in his rag-tag assortment of athletic attire might look fateful in hindsight, Carey’s journey could have ended multiple times along the way. Perhaps that’s why he’s so self-assured today, so at ease with himself, his teammates’ ribbing, the world and his place in it. Maybe, that’s what happens when you face up to failure and forge on.

THERE’S SOMETHING NOSTALGIC, romantic even, about the neat delineation of the sporting calendar that characterised Carey’s childhood in South Australia. Cricket in summer, footy in winter – backyard cricket and kick to kick – if you want to boil them down to their most simple forms. It’s the kind of childhood Paul Kelly should write a song about.

Does it still exist in an age of screens, social media, streaming, gaming and so many other pursuits? For some, perhaps, but even for those who do manage it, the pressure to specialise and pick one sport, to put one dream ahead of another, begins early.

Carey’s dad, who recently passed away after battling Leukemia, coached him all the way through to under 16s in both sports, as his son lived season to season, wilfully ignoring the fact that one day he’d be forced to make a choice. In the end it would be footy that first pressed its claim on his prodigious gifts, mainly due to the game’s national draft.

“I chose AFL at the time because of the draft, whereas in cricket you can be selected from grade cricket,” Carey says. He entered the draft after finishing year 12, though he had already been offered a rookie contract in cricket with South Australia.

He would be overlooked in the first round of the 2009 AFL draft, before being picked up by Team GWS, who were then playing in the TAC Cup. “I was still playing a little bit of cricket when I could, but it just felt right at the time to select footy,” he says.

I ask, somewhat naively, if Carey ever held dreams of following in the footsteps of fellow South Australian Craig Bradley, who back in the ’80s, played footy for Carlton while managing to play the odd Shield game for South Australia and Victoria. “I think nowadays you probably can’t be professional in both because of the way preseasons run and contract situations,” says Carey.

He admits the atmosphere you get at big AFL games with their bumper crowds – his family are mad Crows supporters – might have pulled him toward the pigskin, before adding that these days the Big Bash provides plenty of excitement for younger cricketers and fans.

Carey describes the move to Sydney to play footy as eye-opening. “It was really tough, to be honest,” he says levelly. “There were some pretty hard training sessions, some lonely days away from friends and family.”

Objectively, Carey’s two seasons with Team GWS were a success. He was named Best & Fairest after the first season and appointed club captain; honours you would think might open a pathway to be part of the Giants team for their inaugural AFL season in 2012. Perhaps it would have been enough at another team, but the Giants were a special case. Granted a war chest of top draft picks by the AFL, who were desperate to lay the foundations for a successful Western Sydney team, casualties from the existing list were inevitable. Carey, despite two solid years, would be one of them.

“I thought everything was tracking well to stay on contract, but with the amount of draft picks that the Giants were going to get leading into the AFL, it just pushed me a bit further down the list and I eventually got the bad news from Kevin Sheedy,” he recalls. He would burst into tears in front of the iconic coach. The next day he was on a plane back to South Australia.

At this point it’s tempting to add the requisite, “with his tail between his legs”, or “as one door closed, another would open” but let’s not do that. Carey learned a hard lesson: your fate isn’t always decided by your own hand. The way you respond to setbacks, on the other hand, is something you can control. You might even call it a ‘test’.

WHEN CAREY FIRST got back to South Australia, he didn’t immediately pick up a cricket bat. He needed some encouragement, which he found in the form of Redbacks coach Tim Nielsen.

“I remember sitting down with Tim and he said, ‘If you’re willing to put the time in, we’re willing too. We want to get you back around the South Australian system’,” Carey recalls. “I think it was them showing a bit of love. I guess you want to feel like you’re wanted.”

It’s possible a taste of the real world might have nudged Carey to take the game of flannelled fools a little more seriously. He worked in a call centre at Westpac for a few months, then found himself building other people’s retirement nest eggs in a financial planning firm, the kind of jobs that might make you think a little harder about what you want to do with your life. “All these experiences have definitely helped me appreciate the opportunity we get,” he says.

After playing well with the Glenelg District Cricket Club, Carey earned a call-up to the South Australian side during the 2012/13 season. He thought: “Great, I’m playing professional sport again”. But after just one season he was dropped. Having been successively dumped at the second tier of his two great loves, Carey did what anybody would do in such circumstances; he began to doubt himself. “That was difficult to take and that’s probably when you start to think your professional sporting days are over,” he says.

Ironically it was footy that helped him find a path forward. “I remember clearly, sitting at an AFL game as a spectator and the buzz and the feel of the game just really sparked something within me that I wanted to keep trying to play professional sport,” he says.

In a movie, what came next is the type of scene that’s usually accompanied by a montage and a rousing score, but in real life is characterised by discipline, grit, determination and maybe a little desperation. Carey knuckled down and logged a solid preseason. He put in the work. The rest, he says, was decided by some familiar if sometimes fickle factors – opportunity, timing, luck. “A couple of years later I found myself as the wicketkeeper for South Australia again.”

Looking back, Carey believes part of the reason he was able to fight his way back into the state team was because he’s always viewed setbacks as an opportunity to grow. “They’re just good opportunities to learn,” he says. “You’ve got to keep believing. A setback doesn’t mean it’s the end. Sure, the disappointment is there. That shows it means something to you.”

Failure, he adds, can also free you up. “I think, for me, I was always going to continue to play sport even if it wasn’t at the professional level,” he says. “And I think you play your best when you’re just going out and having fun and you’re not worrying about things that might come.”

In terms of mindset, Carey was back to playing with the freedom, even abandon, he might have enjoyed back in those backyard games with his brother all those years before. Games where you play like you’ve got nothing to lose.

AS CAREY AND I keep chatting in the grandstand, a strong northerly blows a wet mist from a sprinkler onto our faces. Most of his teammates have left for the day, as Carey recalls one of the best days of his life: his Test call-up. It wasn’t quite as he’d imagined growing up, perhaps because once again, while he’d done all he could to put himself in the selectors’ calculations, like many things in life, his big break relied on circumstances outside of his control.

You may recall that back in 2021, the incumbent Australian Test wicketkeeper and captain, Tim Paine, was dropped from the team after a texting scandal. “I guess once you hear the news that he [Tim Paine] probably isn’t going to be part of the Ashes, you start to hope a phone call comes your way,” says Carey, looking back. “I finished a Shield match and [selector] George Bailey called me, but he didn’t say that I was in. He said, ‘How are you going? How are you feeling with everything?’ Blah, blah blah. And I hung up the phone and I was like, I wanted the other call.”

Bailey eventually gave Carey the news in person, in Queensland, where he was playing an Australia A match. He recalls that he couldn’t stop smiling. Fittingly, it would be his boyhood idol, Adam Gilchrist, who presented him with his baggy green.

“If I could ask anyone to do it, it would’ve been Gilly,” says Carey, smiling.

Mitchell Starc would bowl Rory Burns with the first ball of the 2021/22 Ashes series, Carey’s first in Test cricket. He’s been the incumbent Test keeper ever since, relishing his all-rounder role and doing his best to keep Australia’s proud tradition of keeper-batsmen going.

“Batting at seven and wicketkeeping, generally you get to put your feet up for a little bit and watch the top order go about their business and if not, you get to go out and get stuck in,” says Carey, who’s made two Test centuries and boasts a respectable average of 34. “I love both roles in the team and train just as hard on each of them.”

Keeping carries with it a great deal of responsibility – you’re not supposed to drop catches with the gloves on. You’re often the captain’s on-field confidant, sometimes his field marshal and a source of support and enthusiasm for the rest of the team, charged with keeping heads up during long days in the field. It’s these duties that make it a natural fit for a leadership role – Paine, of course, was the team’s previous captain while Gilly served as vice captain. Carey himself was vice captain of the T20 team for a period and has led the ODI team on occasion, a role he admits he enjoys.

“I think it’s one of those things where if you’re a keeper, you’re keeping an eye on the game anyway,” he says.

Sometimes though, the keeper’s proximity to the action can make them the centre of attention – and the subject of controversy – as Carey would find out in the 2023 Ashes.

IF YOU’RE NOT a cricket tragic, there’s a good chance you first heard of Carey due to his role in one of the most controversial on-field incidents in recent memory: the run out of England’s Jonny Bairstow during the Lords Test in the 2023 Ashes series.

To refresh your memory, Bairstow had ducked under a bouncer from Cam Green and assuming the ball was dead, ambled down the pitch. Only the ball wasn’t dead and Carey, seeing an opportunity, threw down the stumps. The Poms were outraged, the crowd incensed and the British tabloids had a field day. Even Prime Ministers weighed in on whether the run-out was in the ‘spirit of the game’. Carey smiles coyly when I ask what it was like to be at the centre of such an incendiary incident.

“I guess at the time it got pretty hostile out there and the feedback straight away gave us a good indication of what it was going to be like after it,” he says. “It was made pretty clear to me at Leeds, in the next Test, when I walked out to bat and the whole stand was chanting “If you hate Carey take your shoe off’ and then everyone had their shoes above their head singing it.”

Carey became a target for the yobbos on the terrace, as well as the keyboard crowd on social media, for the rest of the series. The controversy was made more difficult for Carey by the fact his wife and kids were watching on from the sidelines. “I was trying to protect them,” he says. “When you’re copping that much abuse, you can second guess yourself a little bit.”

You can, but as Carey has shown throughout his topsy-turvy sporting career, that’s not something he engages in for too long. Carey expects to be a target for the Barmy Army for the rest of his career. He doesn’t seem overly phased by the prospect. Should he find himself greeted with a shower of shoes as he walks out to bat this summer, you can bet he’ll cop it sweet. He’ll smile. And then, he’ll do what he always has: he’ll press on.

Alex Carey’s workout

Carey’s commitment to fitness means his body hasn’t changed too dramatically from his days as an Aussie Rules player. He tips the scales at 83-84 kg, compared to 78-80 kg back in his days at the Giants. “I was a little bit leaner and a little bit lighter [in Aussie Rules] just because I was trying to run further and a bit faster,” he says.

Carey’s workout is designed to build the explosive force and lateral lower-body movement required to leap in front of the slips cordon, prevent byes and yes, to scamper to the stumps to effect run outs.

Warm-up

- Box jumps x 3

- Base jumps x 3

- Skater hops x 3

- Skipping x 1 min

Main set

- Trap bar deadlifts 4 x 5

- Lateral box jumps 3 x 8 each side

- Box jumps 3 x 8

- Cable-rows 3 x 8-10

- Bench press 3 x 8-10

Core work

- Candles 3 x 10

- Seated plate rotation 3 x 10 each side

Win the mental game

Wicketkeeping and batting require intense periods of focus and concentration, repeatedly, all day long. A lapse means a dropped catch, glares from a fast bowler and boos from the crowd. Carey relies on mantras to stay focused – “Watch the fucking ball” – one of his most pointed.

When batting, he likes to berate himself a little, which he believes helps him focus, kind of like a boxer hitting his face before a bout. “I’ll swear at myself a little bit if I need to,” he says. He also aims to keep his heart rate elevated. “I’ll sprint out to the middle when a wicket falls and get my heart rate up. I want to be at a higher intensity. I feel like that’s when I’m focused and sharpest and I don’t have any distractions. As soon as I get distractions and start trying to premeditate it’s a bad place to be. So, I’ll tell that distraction to F off and make sure I’m back to just reacting and watching the ball.”

Words: Ben Jhoty

Photography: Chris Ferguson

Styling: Grant Pearce

Production director: Rebecca Moore

Fashion assistant: Kailee Waller

Grooming: Chris Coonrod

Design: Evan Lawrence

Video: Bailey Hill