As strange as it sounds, Diego Mercado’s journey towards a crisis began at a cinema in the Bronx when he was 16 years old. Mercado was sitting in a multiplex when he saw a dude rip off his shirt in a Twilight movie. “Like, you see that awesome aesthetic body. Like, oh man, I want that.” Right there, he decided that he had to build muscle – a six-pack, too. He wanted to have a body that everyone knew was in great shape. So, the sophomore hit the weights.

At first, he worked out at Planet Fitness. But as he got more serious, he sought out a more serious gym. Star Fitness in the Bronx was hardcore – full of competitive powerlifters, bodybuilders and other guys who made strength training part of their identity. He was reading every PubMed study on testosterone and anabolic protocols when he should have been attentive in his high-school classes. Mercado immersed himself in gym culture, feeling passion and peer pressure to look the part. He was way bigger and stronger and fitter looking than he had been before, but he noticed that some of his friends who didn’t seem as committed as he was were making faster progress. He desperately wanted to make greater gains.

IG @dmercadofit.

After learning he had low testosterone levels, Mercado wound up taking a stack of anabolic compounds without medical supervision. He became obsessive about training and dieting. Mercado was crushing two or even three sessions at the gym daily. To micromanage his food intake, he was toting a scale to the Mexican and Cuban restaurants where he worked as a server and bartender. He also was camping out on Instagram, exuberantly sharing his quest for muscularity and mainlining the fitness content of other ripped guys. His Instagram account, which he’d later scrub, was packed with images that showed his arms stretching the limits of his T-shirts and his big-screen-worthy abs.

“It felt like going from Clark Kent to Superman,” Mercado says. When he was at the gym, he suddenly felt like he was always his best self; his confidence and energy levels skyrocketed; the compliments from those around him poured in. He scuttled plans to become an engineer and focused on fitness. “I became so obsessed. It took over my life without me noticing it. I literally became a different person.”

But in July 2019, that person wound up having the scare of his life. He was out late at a club on a Saturday night with friends when he started to feel unnaturally hot. Though he’d felt hot from the steroids before, it was nothing like this. He went home and crashed but woke up in a pool of sweat. His head was pounding. “I felt like I was dying,” Mercado recalls. He knew he had to get to the emergency room. There, as he lay on a gurney, doctors told him his hemoglobin count was so high that his blood was getting sludgy.

All Mercado had ever wanted to do was gain muscle and be strong. He had no idea that he would eventually grapple with the consequences of muscle dysmorphia (MD), a disorder that’s characterised by a desire to get muscular and lean and that can take over your life.

“The day you start lifting is the day you become forever small”

In one sense, Mercado is lucky – he got his wake-up call before he had a heart attack or stroke. Now 22, he remains passionate about fitness and works as a personal trainer, and he can do so with the wisdom of someone who knows how to do it right. Still, Mercado carries a heavy burden. His hormone production may be altered for life, affecting everything from testosterone to serotonin. And it’s tough to be a personal trainer or fitness influencer in this social-media age if you’re not jacked.

When asked what advice he’d offer young men about going all in to get muscular after his struggle with dysmorphia, Mercado’s voice cracks. “Don’t do it unless you’re okay losing everything and everyone you care about,” he says. “You can wind up at less than zero.”

Warped perceptions

Muscle dysmorphia is an enigma, studied for decades but still not seen as a public-health crisis like eating disorders. Researchers estimate that MD impacts about one out of every 500 adult men, but those numbers do not reflect the large group of men who don’t meet the clinical criteria yet struggle with urges to get bigger. One 2019 University of California, San Francisco study of young American adults found that more than a fifth of men engaged in muscularity-based disordered eating behaviours. And a 2018 study of adolescents found that roughly 40 per cent of boys who were of normal weight were actively trying to gain weight and get bigger. Other research has indicated that up to 54 per cent of competitive bodybuilders and 13 per cent of men in the military suffer from MD.

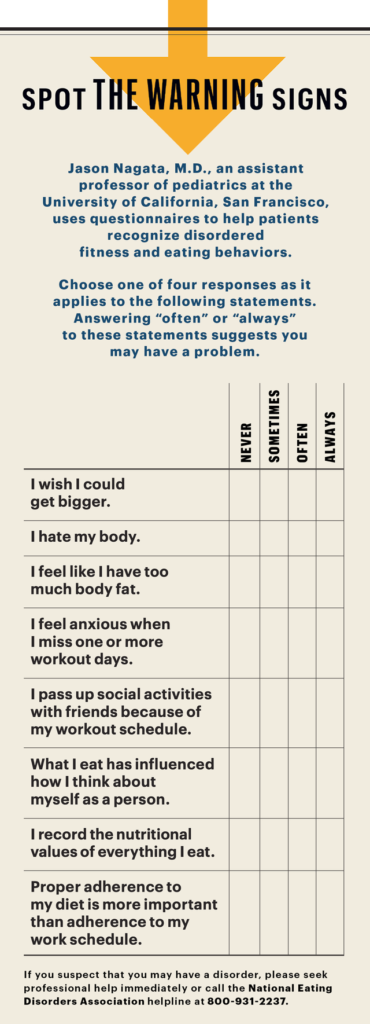

Men with muscle dysmorphia are preoccupied with feeling small or insufficiently muscular. But to meet the criteria, it takes more than dissatisfaction with your body or a fixation on lifting, says Dr Jason Nagata, an assistant professor of pediatrics. “Muscle dysmorphia comes with an impairment in daily functioning,” he says. “Men with MD obsess about weight, food, exercise and/or appearance in a way that worsens their quality of life.” This typically translates into feelings of significant distress and a disruption of one’s personal, work or school life.

Most guys who’ve lifted weights seriously have some perspective on the problem. That urge to get more muscular; the lurking frustration if progress comes slowly; the way you can slide into overtraining or obsessive dieting to reach goalposts that keep shifting; the way you can feel consumed with wanting to get bigger. There’s even a classic bodybuilding line that encapsulates the underlying preoccupation: “The day you start lifting is the day you become forever small”.

Muscle dysmorphia has been in the news lately, framed as a disorder of the moment. While there’s no epidemiological data yet substantiating a higher incidence of MD, all the experts interviewed for this story see evidence that the problem is growing. So what’s changed? The idealisation of the male physique is hardly new. Arnold’s pecs made him a movie star in the ’80s. And then magazines like the one you’re holding celebrated a hyperidealised masculinity in which ripped abs became the emblem of living your best life. A generation of guys absorbed Fight Club and Abercrombie & Fitch branding and Calvin Klein billboards. This muscle-bound vision of masculinity became inescapable – it was even in the action figures kids played with.

But in recent years, that cultural saturation has accelerated. Now practically every Marvel character not played by Jon Favreau is jacked. Use of muscle-building supplements and drugs – ranging from creatine to human growth hormone and anabolic compounds – has grown into a multibillion-dollar love affair. And social media has been like lighter fluid on the fire. “In the past, you were in read-only mode,” says Nagata. “Now with social media, everyone can become an influencer. Boys’ bodies are on display.”

I see the impact in my own household. My younger son, who’s 15, has gotten into lifting. He and his mates hit the gym six days a week. They’re more interested in having defined abs than in building basic strength. They’re drinking protein shakes and scheming to get creatine. They talk about getting big. Teenagers have wanted to be

buff for a long time, but there’s something different about how this generation experiences it. My son’s Instagram and TikTok feeds are full of dubious inspiration – a stream of shirtless torsos, bodybuilder types who insist their physiques are natural despite evidence to the contrary, acquaintances who are ripped, and young influencers who are more ripped. We’ve reached a point where teenagers who obsessively work out and make content in their bedrooms exert legit cultural influence.

But don’t take my word for it. In a 2020 study, researchers analysed 1000 Instagram posts that were created by men and/or depicted men, to clarify how the male body is portrayed on social media and how people react to these images. The majority of the posts showed a full body or upper body, and the majority of the men were lean and muscular. The results indicated that posts of leaner, more muscular men yield significantly more likes.

“The main takeaway was pretty obvious – that while women focus on beauty and being thin, for men it’s about being lean and muscular,” says Thomas Gültzow, an assistant professor of applied social psychology and the lead author of that study. “Of course, most men don’t look like this, so there’s clear misinformation between Instagram and real life. But nonetheless, lean and muscular men get more engagement. Engagement is the currency people have now. And with how algorithms function, those men get attention in the future, too. It’s a vicious circle.”

To complicate matters, many social-media users manipulate photos to make themselves look more shredded than they are. It’s a sad reality that the term “half natty lighting” exists, but indeed the Internet is full of advice on how to photograph your body to suggest you might be taking PEDs. The problem has gotten so intense that multiple studies have examined the contours of so-called Snapchat dysmorphia, disordered behaviour characterised by a loss of perspective on your own appearance due to heavy editing and filtering of images on social media. Some people even explore cosmetic surgery to help them resemble filtered or manipulated images of themselves. It’s all part of

a disturbing continuum in which people have trouble differentiating between what they see on social and what is real. Dr Katharine Phillips, a professor of psychiatry at Weill-Cornell Medicine, says that men with muscle dysmorphia have “aberrations in visual processing”, meaning they don’t see themselves accurately and often presume what they see on social media is attainable.

Plus, social-media users aren’t just consuming a buffet of rippling pecs – they’re gorging on information (and misinformation) on how to get them. Everyone has an awesome cheat meal and a favourite bulking hack. It’s a cacophony that can make something simple seem fraught. “Young people today feel pressure to be the best at something or to stand out,” says Roberto Olivardia, a lecturer in psychology at Harvard Medical School. “And the body is a very salient thing.”

This is the filter through which I observe my son. I know there are tonnes of positives – strength, discipline, confidence, community – to be found at the gym. But I also see the kid saturated with aesthetically oriented content, and I know from three decades of gym memberships all the compulsions that lurk wherever 20-kg plates are racked. I love to see him spot his buddies on the bench, but I also love to see them skip leg day to play hoops. Because if you lift a lot, you know it can get out of control.

Tale of obsession

George Mycock, 26, understands that fixation. He grew up in a small town in England, where he played rugby as a kid. But when he was 13, after fracturing his spine in a game, Mycock spent a year bedridden. And by the time he got back to school, his weight had nearly doubled. The formerly brawny athlete wanted to regain his peers’ respect, so he started dieting and exercising. Mycock now knows that his bingeing and purging was disordered. But at the time, he noticed how people showered him with praise for losing weight and getting fit.

Eventually, he turned to social media for inspiration. “All the guys were massive and muscular people,” he says. “So I thought, That’s what I need to be.” He began lifting and eating more. Things got out of hand during his first year of college. “I spent the entire year in the gym. I studied in the gym, I trained two or three times a day. I was literally there all the time,” he says. “And whenever, out of exhaustion, I was unable to train, I’d lock myself in a room and binge-eat.”

His life revolved around muscularity. “All my media sources, my entire Instagram, was just bodybuilders and fitness influencers,” he says. When he wasn’t bingeing, he was weighing his food like a scientist and doing push-ups when he went to the toilet at work. And though his IG feed offered proof that his delts and triceps were growing, his IRL social circle was shrinking.

“If I posted a photo and it didn’t meet my expectations, it wasn’t just, ‘MY arms look small’. It was, ‘my arms look small, and I don’t look manly,

Therefore I’m not a good person and I should die’.”

Clinicians identified the symptoms of this sort of obsession in the ’90s. They coined the term “bigorexia” for

it, suggesting the opposite of anorexia. Now most experts prefer “muscle dysmorphia”, since MD sufferers don’t necessarily struggle with disordered eating. It’s classified in the broader category of body dysmorphic disorder. Phillips has studied and treated muscle dysmorphia for more than 30 years and has witnessed the obsessive preoccupations that characterise MD. Young men who end up in her care are often in severe distress. They may spend three to five hours a day worrying about their appearance. They likely have a preoccupation with looking at themselves in mirrors, as well as significant mood problems. “It can be quite severe,” Phillips says. “Some people wind up housebound. There’s an association with suicide.”

Still, for a condition that’s been studied so long, much remains unknown. Relatively few men with MD seek help from a doctor. And few well-designed studies have compared or substantiated treatment options. “Up until now, the vast majority of research on eating disorders and body-image problems has focused on females,” says Nagata. “Because there have been so few studies on men, there’s not great data.”

It’s hard to treat a problem on a large scale without more knowledge. Thanks to decades of research and messaging, the public now knows that men have body-image problems and eating disorders. In fact, about 30 per cent of people with eating disorders are now men. But despite that progress, cultural barriers to accepting men who obsess about muscularity remain.

The preconceptions about masculinity that pervade male culture and the medical establishment run deep. Consider how attitudes have evolved so people feel empathetic to people struggling with anorexia and bulimia. Now imagine that deep compassion being extended to men who relentlessly chase muscularity. “People don’t have empathy for someone who looks threatening,” says Olivardia. “That’s the paradox of muscle dysmorphia: you have men who are big and muscular, which suggests a level of dominance and threat. But internally, the men often feel incredibly small.”

Mycock witnessed those cultural barriers when he went to see his physician for a check-up. “He looked at my records and said, ‘Oh, it says here you have an eating disorder’ and he flexed his arm at me,” Mycock remembers. “And he looked at me and said, ‘You obviously don’t have one’. ”

Things came to a head for Mycock in his second year at college. He started having thoughts about suicide, even thinking about how he’d do it. “Social media played a dangerous part,” he recalls. When he posted a good photo of his body, he admits, “the likes that I would get would definitely affect my mood more than they should have.” And it was a crisis if a photo didn’t meet his expectations. “It wasn’t just like, My arm looks small in that photo, it was, My arm looks small and I don’t look manly, and therefore I’m not a good person and therefore I should die.”

Luckily, a friend got Mycock to open up. Soon thereafter, he began seeing a therapist. Some of the old compulsions still remain, but Mycock has found peace by being way more honest with himself and those around him, developing strategies to manage his urges, and reorienting his fitness goals around function and sports rather than aesthetics. These days, Mycock runs a mental-health organisation called MyoMinds, produces a podcast and is working to create training courses to help PTs, coaches and doctors understand and recognise the mental-health conditions that commonly affect exercisers, all aspiring to improve men’s access to mental-health tools. “I noticed that when I shared feelings about my body and food with my friends and gym buddies, almost all of them said that they had similar thoughts,” he says. “A lot of guys who take fitness seriously are struggling with these thoughts.”

Within the medical establishment, the standard of care for muscle dysmorphia is typically a multipronged approach. Phillips urges the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy to help guys get control of repetitive behaviour, develop strategies to interact with other people and recast errors in their thoughts. She also says that SSRIs like Prozac and Zoloft help patients rein in obsessive thoughts and behaviour, like the wish to isolate.

Still, more than 30 years after muscle dysmorphia was identified, few guys get treated. While eating disorders have commanded tonnes of attention and research and public conversation, muscle dysmorphia has lingered in the shadows, something that bodybuilders and the lifting faithful talk about with little notice elsewhere.

Big problems

While social media is helping bring muscle dysmorphia into the public eye, something more fundamental needs to change. We need a new conversation that better connects male culture, strength-training communities and the medical establishment. Call it a reckoning.

For starters, the scope of MD is bigger than acknowledged. “There’s definitely a lot more people out there who are not identified,” says Olivardia, dipping into what experts call the subclinical range. Think about people who binge and purge or have a drinking problem but don’t meet the clinical criteria for bulimia or alcohol-use disorder. “Subclinical is a real misnomer because it assumes that it’s less serious or that there’s less morbidity or mortality, and that’s not true at all.” People in that subclincal range, he says, are like functioning alcoholics – at risk, unlikely to be identified or seek treatment, vulnerable to long-term impairment.

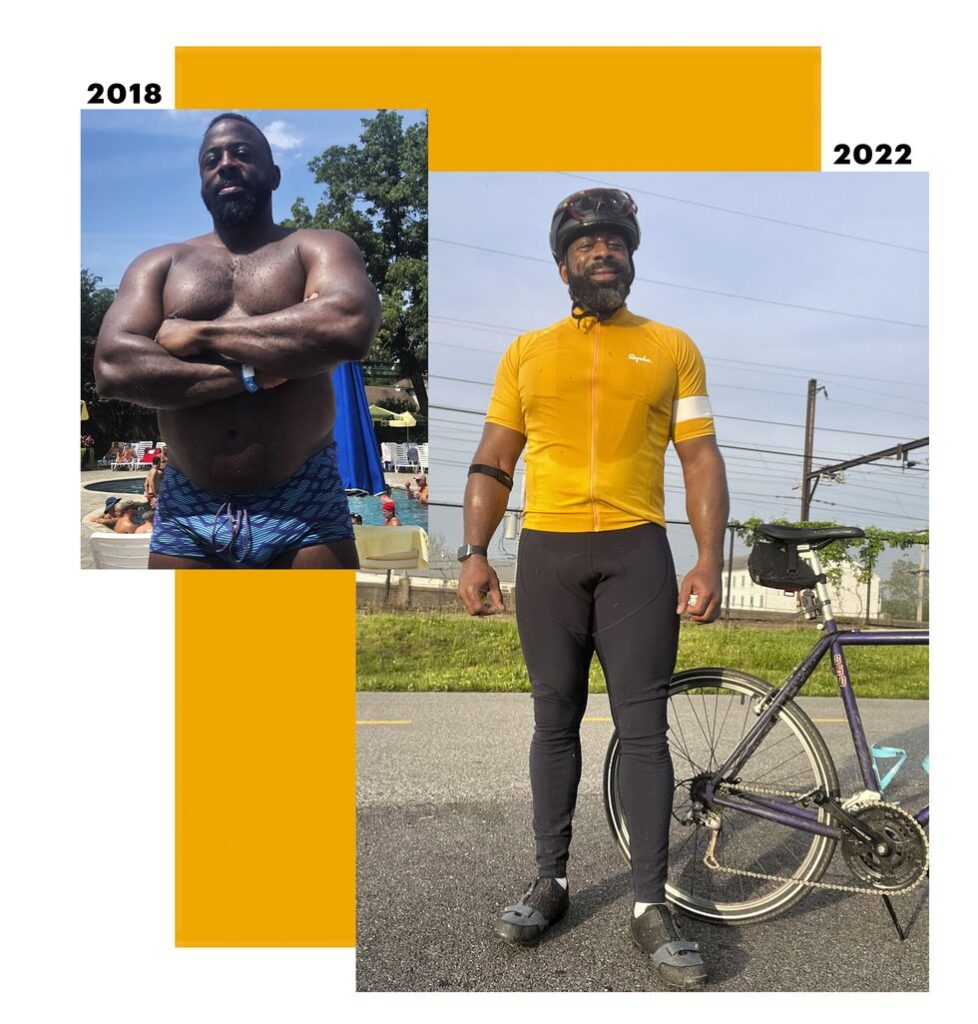

Marc Coleman is in a good place now, but it could have been different. Coleman, the 53-year-old founding CEO of a software-development agency, has been lifting for three decades. “When I was in my 20s, I couldn’t get big enough fast enough,” he says, noting that back then he packed 113 kilos onto his 180cm frame. “When I looked in the mirror,

I just saw this skinny person.”

His inflection point came when he blew out his shoulder. He couldn’t raise his arm above his head and was in constant pain, but he kept lifting. “I was worried that my chest or arms might shrink, and that seemed worse than not being able to move,” he says. Eventually, only when he was faced with a choice between physical therapy and surgery did he take a break. These days, Coleman mixes things up more. He works out five times a week and splits his time between lifting and cycling. A balance of sorts. But, he admits, the old preoccupations still linger. “Now I’m just more interested in being fit. But honestly, that can feel like the same kind of pressure.”

Oftentimes our compulsions change shape rather than disappear. These issues don’t resolve themselves if men don’t talk about them. Men with body-image disorders like MD can get help only if there’s an honest conversation, one that includes the guys who struggle with the problem and the medical experts who treat them.

A new study examines how doctors might better engage in that conversation. That research, led by Mair Underwood, an anthropologist at the University of Queensland, takes aim at mental-health professionals for acting as experts on the pathological behaviour of bodybuilders without absorbing the cultural experience of men who wrestle with the condition. “There are two discourses on muscle dysmorphia – the medical one and the bodybuilder one. I’m trying to bring the two together,” she says. “Bodybuilding isn’t inherently psychopathological, but the medical community implies that it is.”

During the course of her research, Underwood became embedded in lifting culture and trained hard to reach aesthetic goals. She says she was in the best shape she’d been in since having kids but had wild swings in body image and came to hate small imperfections. “When you’re focusing on your body that much, your feelings get out of proportion,” she says.

Underwood’s research documents how muscle dysmorphia is normalised within bodybuilding culture – how participants think it’s part of the pursuit of muscular perfection. This community perceives the condition on a spectrum, with many guys viewing minor symptoms as a positive, motivating them to train harder. Her study found that bodybuilders talk openly to one another about MD, which is particularly important, as very few of them will seek help from the medical community. One reason they don’t is that the treatment will typically involve giving up behaviours that are considered normal in the bodybuilding community, such as long hours of training and steroid use.

The medical establishment needs to try harder to reach the people who need help, says Underwood: “If only a small percentage are presenting for treatment, there’s all these young guys suffering out there.”

A new way of seeing

For Diego Mercado, the guy who wound up in emergency with blood like sludge, fitness means something else now. His experience has in many ways made him a better PT. He has hard-earned wisdom about balance. He knows that being healthy is more important than being ripped.

These days, his IG feed is big on thoughtful inspiration and helpful tips rather than muscle-bound eye candy. In short, he’s using social media to share his struggle with muscle dysmorphia to help other people avoid the same fate. “The real glow-up is when you stop waiting to turn into some perfect version of yourself and consciously enjoy being who you are in the present,” Mercado noted in a recent post. Another observed: “Comparison is the thief of joy. And your biggest competition is you 100%.” Mercado says he now realises his journey was really learning to love and respect himself. “Most people think of confidence as a mindset or character trait,” he says. “Confidence is a skill that you earn. It comes from keeping the promises you make to yourself.”

Mercado is not the only next-gen trainer using social media in new ways. Ryan Schwartz, a 40-year-old PT and life coach from Montreal, learned how things can spiral out of control. When he was 21, Schwartz, at 168cm, was 135kg. He collapsed after a party and woke up on his back underneath a black sky. “I thought I was dead,” he admits. A radical lifestyle adjustment followed – no more booze, drugs or cigarettes. He replaced those vices with diet and exercise. In about a year, through extreme discipline, Schwartz almost halved his weight. He was way healthier than before, but he wound up with a compulsion to get ripped.

Like Mercado’s, Schwartz’s journey to balance had a layover in the emergency department. Back then, he was doing three-a-day workouts on a strict 8000-kJ keto diet. “Honestly, it was hell. I was never happy,” Schwartz says. “I got stuck always chasing that aesthetic. I wasn’t paying enough attention to my wife and kids.”

But one day, it finally caught up to him. Feeling awful, he raced to emergency. A doctor told him that he was severely dehydrated and his kidneys were shutting down. So, as he did after his collapse at 21, Schwartz took radical action. “From that day forward, I changed my mindset… to pull the focus away from what I looked like and instead to think about what’s healthy,” he says.

“From that day forward, I changed my mindset… to pull the focus away from what I looked like and instead to think about what’s healthy”

In his current work as a trainer, Schwartz helps clients adopt that mindset. “Young people are constantly bombarded with the highlight reel of every person’s day,” he says. “And we sit there and think, I look like shit, everybody else’s life is awesome.” Schwartz encourages clients to focus on their health and forget about pursuing perfection. And he talks to himself like he’s a client, too – urging balance and self-kindness.

Schwartz thinks there needs to be a grassroots effort to drag muscle dysmorphia into the conversation. “The difference between men and women is that men need to come to that rock-bottom moment before they look for help,” he says. “That’s why I think we need to push out more of these kinds of stories, to make it a safer space for guys.”

If you suspect that you may have an eating disorder, please seek professional help immediately or call the Butterfly Foundation’s helpline on 1800 33 4673.

This story appears in the March 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

Words: Peter Flax.