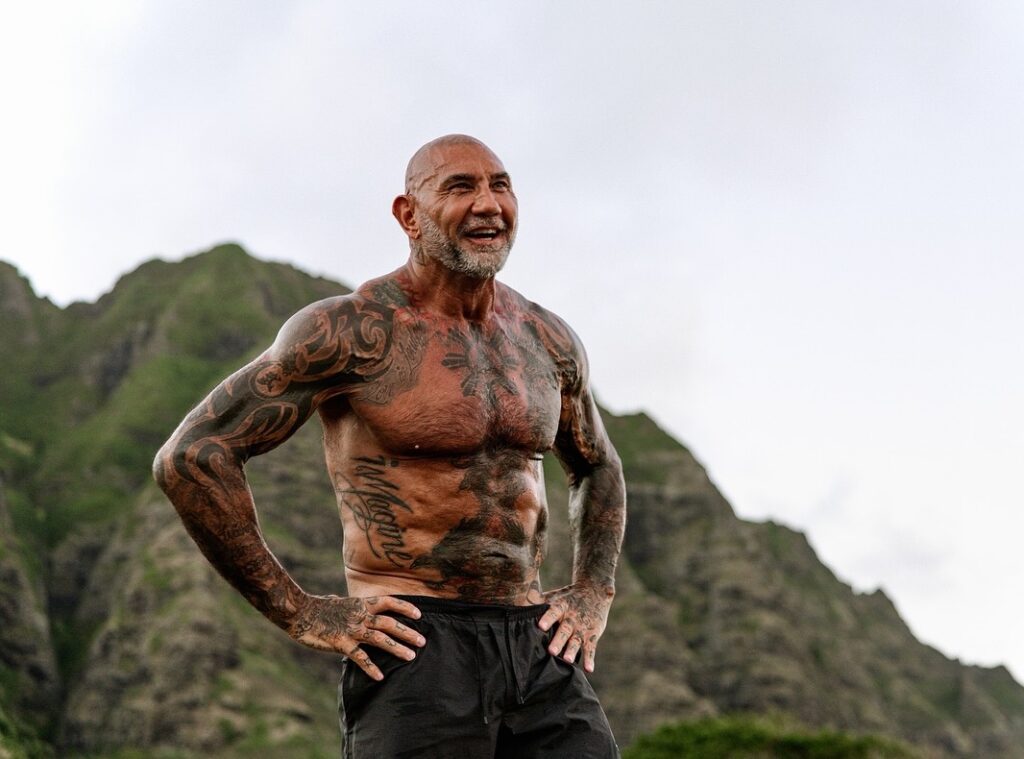

Ready For His Close-up: Chung may finally have found the role that propels him to stardom. PHOTOGRAPHY BY PIP

Chris Chung remembers the day he realised he’d made it. He was playing the role of Paris in a production of Romeo and Juliet at London’s Globe theatre. It was a coveted role in an auspicious production – performing Shakespeare at the Globe is on many actors’ bucket-lists – yet it wasn’t the rarefied stage that had Chung feeling goosebumps. It was who was watching him.

“There are two big doors in the middle of the stage and you can see through these little grates and there was this little Asian kid down there who looked exactly like me when I was his age, with glasses and the fringe,” he recalls. “And I was just like, Oh my God. I never saw myself represented on screen, let alone stage when I was growing up. And I get to be that for someone else today.”

It might not seem like the most obvious breakthrough moment for an actor who is still very much chasing the dream. One, who by most estimations and by the scope of his ambitions, definitely hasn’t made it. But when you look at Chung’s career and the hurdles he’s had to overcome in pursuit of becoming an ‘overnight sensation’, that day, as much as any other, feels like a victory.

“Maybe him seeing me on stage would make him think that he can do more than what he thought he could before he came to the theatre today,” Chung says. “I think that’s the power of being an actor and being able to plant seeds like that.”

Chung and I have spent nearly 90 minutes talking about hopes and dreams, breakthroughs and false dawns; how difficult it can be as an actor from an ethnic background to break out of playing stereotypical or box-ticking characters and to be cast in meaty roles, on merit. And how your mindset can shape the way you approach life’s big opportunities, casting dye in the alchemy of fate and circumstance, either tilting things in your favour or seeing them slip through your fingers.

The reason we’re chatting today is because Chung is starring in the new spy drama, Slow Horses, currently screening on Apple, in which he shares the screen with luminaries Gary Oldman and Kristin Scott Thomas. It’s the role that could launch Chung’s career, opening doors that might lead to stardom. Or it could be a flash in the pan. Another false start in a career that’s seen its fair share.

The stakes are high, in other words. Or are they? After years of angst, in which he’s both projected triumphs and plotted disasters, second-guessed choices made and regretted opportunities ungrasped, all while battling to find a footing in an industry in which the dearth of opportunities for actors of diverse backgrounds is close to systemic, Chung might finally be in a frame of mind that not only primes you for success but also allows you to absorb disappointment. And if you can pull that off, well, you truly are on your way.

Against the odds

Chung’s talking to me from his childhood home in Mount Eliza on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. He’s back from London where he’s been based for the past decade to visit his family for Christmas. It’s where Chung grew up, a biracial boy with a bowl cut – his father is Chinese, his mother Irish – in an overwhelmingly white community. Being home has given Chung pause to reflect on his childhood and just how much of an anomaly he was here back in the 1990s, one of only four kids of East Asian heritage in a high school of 2000 kids. When you’re that small and that different, it’s not so much the overt racism – though there was enough of that around – that wounds you. The real problem, Chung says, is you already hate yourself.

“For the longest time I wanted to be white and that’s really fucked up,” says the muscular 33-year-old, who’s wearing a fitted grey T-shirt, as he sits in a swivel chair in his parents’ study. “When you really think about it on a fundamental level, it’s like you have such a crisis of identity because you see how the colour of your skin affects the way you think about your place in the world. It’s messed up. I had to have a conversation with my parents when I came back about how growing up here as someone of a different colour skin affected me. They’re like, ‘You’re not different. You’re not a different colour’. I’m like, ‘What are you talking about? Look at the people I grew up with’. They don’t see it, which is mental to me.”

Perhaps the reason his parents were oblivious to their son’s distinction from his peers is because, back then, Chung never made a big deal about it. Instead, he would laugh along when kids made fun of him. “It’s only recently that I’ve come to realise that there’s a lot of things in my past, growing up in a community that’s predominantly Caucasian, that I let people get away with just because I didn’t want to rock the boat,” he says.

Because what would that achieve, really? Likely he’d have been told to stop being so sensitive – it’s just a joke, mate, lighten up. “You want to laugh and you want to get along,” Chung says of the insensitive remarks, rooted in racism, that were passed off as jocular ribbing. “You almost make fun of yourself to be part of the joke, rather than be that joke. It’s really not right.”

This kind of self-loathing can cause lifelong resentment, if you let it. Chung hasn’t. Having these conversations with his parents and friends reveals a man whose pride in

his identity has emboldened him to both confront the demons of his past and call out instances of discrimination that still persist.

Because childhood wouldn’t be the last time Chung would feel different. In choosing to pursue acting he would commit himself to an industry that, until perhaps the last five years, wasn’t particularly diverse. Being different was something Chung was going to have to live with. And it would make the fight to break through that much harder.

Whatever It Takes

Chung’s first love was singing. His older sister performed

in musical theatre and Chung, who was 10 years younger, used to go and watch her. “I always wanted to be up on stage,” he says. “I was always doing shows in the living room for my parents or for guests that would come over. Anyone who would listen to me or give me attention.”

In Year 6 he landed the role of Aladdin in the school play. It was his first taste of acting and a seed was planted, he says. But his heart was still set on singing. He would try out for Popstars when he was 15, lying about his age to get through to auditions in Sydney. He also made the top 100 in both Australian Idol and The X Factor. “Ronan Keating, Guy Sebastian and Natalie Bassingthwaighte all said yes, and Mel B said, ‘You’ve got nice body, but that’s about it’,” he says of his experience on X Factor.

Next, he landed a role on Neighbours, playing a drug dealer at Lassiters – what else would an Asian guy play in Australia’s white suburban utopia? But it was a half-day’s work that would prove conversational gold once he got to the UK. “Every time I go anywhere in the UK, it’s like ‘Done an episode of Neighbours?’ Everyone’s crazy excited about that. I have also played the Globe, but that’s what they want to talk about. Fair enough.”

By now Chung had settled on acting. At 21, after attending some classes by a visiting American acting teacher, he decided to go to New York to do an intensive course with her. “I was like, if you really want to do this as

a career, these are the things that you’re going to have to do,” he says.

Part of that was ambition. Part of it was that with his Asian heritage, he simply couldn’t see there being opportunities for him to succeed here. “At that point in time, in 2008 to 2010, the diversity in the casting here was not as great as it is now,” he says. “I couldn’t see myself . . . I’ve never been able to see myself reflected on screen here. I think that is marginally changing. I come back and it’s not just Lisa McCune on TV all the time. But I always knew that if I wanted to do what I wanted to do, I was going to have to go elsewhere to really push for it.”

Chung threw himself into his acting classes. It helped that his teacher liked to use training analogies to motivate her students, a tactic that resonated with the recently qualified PT. “She was always really pushing us to understand that acting is a muscle, just like any other muscle,” he laughs. “You work your biceps, it grows. So, you’ve got to work your technical skills, work your emotional life. I took to that mentality.”

After the course, he headed to London where he booked a big, glossy commercial that also happened to star Crazy Rich Asians and Eternals star Gemma Chan.

“I think it was the first professional gig for both of us and obviously now she’s a Marvel superhero.”

In 2013 Chung got his first real job, landing a role on the popular BBC soap Waterloo Road. It was a meal ticket. It was the role, Chung thought, that was going to launch him. “I was 24 and I thought that was going to be a big break for me,” he says. In fact, it would be seven years before he would land another TV role.

Own worst enemy

Every actor needs a fallback, whether it’s pouring pints or waiting tables. For Chung it was building bodies. He got his PT qualifications in Australia and after arriving in London worked at Virgin Active for eight years before taking on private clients.

He’d got into training after battling body-image issues as a teenager. “I was a really overweight kid up until about 16,” he says. “Looking back now I definitely had an eating disorder where I just wouldn’t eat carbs for two years. I didn’t eat any rice. I grew up in an Asian household. There’s rice every night.”

Training helped him shed the weight but it also brought out his innate obsessiveness. “I’ve spent a lot of time in the past trying not to use my training as punishment for what I eat,” he says. “I’m obsessive about most things in my life but right now I’m trying to work on how can I balance the two of them and not break myself.”

These traits, obsessiveness and anxiousness, would be inevitable companions in his acting journey, too – they are for many actors. There’s something about baring your soul for an audience that seems to invite unhealthy levels of introspection, but it’s perhaps worse for stage actors, who must strive for perfection without the luxury of another take. For Chung, insecurities about his dramatic chops were brought to the fore when he began auditioning for roles in the London theatre scene, a snake pit of ambition and talent, with so many high-pedigree actors jostling for parts.

“In somewhere like London everyone has this foundation of really fucking great acting training from a top drama school,” he says. “It’s quite intimidating to go into a room with someone that has RADA (Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts) on their CV and you don’t. So, I never really thought I could hold my own against people like that.”

For a while he couldn’t, getting in his own way as he tried to anticipate what casting directors might be looking for. “It was only when I stopped trying to think, ‘This is what they want, this is how I can get this part’ and I just was like, ‘All right, what do I enjoy?’ that things started to change for me. I started to see that this way makes me better. This makes me just as good as someone who’s been to one of those drama schools.”

The role of Paris in Romeo and Juliet loomed as a potential career highlight. But if he was anxious about auditioning for it, his nerves would really fray once he actually had to perform. “To read Romeo and Juliet with the director at the Globe was enough,” he says. “But to get the job, it was flabbergasting.”

He would suffer from crises of confidence. He’d have meltdowns. He would wonder how he was possibly going to get through it. He’d had the same experience on a musical production of Heathers. What helped him survive was realising everyone else was going through the same thing. Part of the thrill of live performance, he says, is taking something from scratch and slowly but surely turning it from a blunt instrument into a blade. “It’s the growth that comes from being uncomfortable that I really love about theatre,” he says. “You always end up doing something that you didn’t think you could do at the start of the rehearsal process.”

Now or never

As much as Chung enjoyed the theatre, though, he always wanted to get back into TV and from there, hopefully, movies. In those seven years after Waterloo Road, he auditioned constantly without landing anything substantial. The process wore him down. When he got an invitation to interview for a show called Slow Horses based on Mick Herron’s cult Slough House spy series, he felt it was his last best shot. If he didn’t get it, he was ready to throw in the towel and become a PT fulltime.

“I’ve had a lot of success in London but I think it had come to a point where my mental health was really struggling with the uncertainty of this career,” he says. “I’m a man in my thirties. I’d just gotten married. Me and my wife want to have a kid at some point. The instability of being an actor, financially, is really scary at times. I’m lucky enough to have two careers and I can move into being a personal trainer full-time if I need to.”

One thing his old acting teacher had told him resonated with Chung then. “She always used to say that just when you’re at the point where you’re about to give up, the most exceptional things will happen. You really have to be at your wit’s end.” Why might that be? “I think sometimes when you’re at the point of, ‘Fuck, if this doesn’t work out, I might have to reassess’, it forces your hand to be like, ‘Fuck yeah, I’m going to be brilliant right now’.” He also received some advice from his sister, who called him before the audition. “She’s like, ‘Don’t go in and think, Oh God, I hope they like me’. Because that’s how you feel a bit beholden, like I’m so lucky to be in this room because they could’ve chosen anyone. Nah, not anymore. You’ve got to think, how fucking lucky are they to have me in this room right now? That’s the change in mindset.”

The audition was in mid 2020. It was his first in person after lockdown in London. He remembers coming out of it thinking it couldn’t have gone any better. Then came the wait. A week went by and he started to fret. His agent said it could be the next week. “In that situation, you have all these thoughts in your head that never end up being the actual case,” he says. “You’re always thinking of the worst-case scenario, because in reality you have no idea what’s going on. It’s your brain playing tricks on you.”

The call from his agent came at 5pm on Friday of the second week. “She said, ‘Hey, happy Friday’. I said, ‘Who did they give it to?’ And she’s like, ‘Now, why would I be saying it’s a happy Friday?’ I said, ‘Fuck off. No way’. I absolutely lost it.”

Of course, as always, once you land your dream part, there’s still the small matter of performing it. Immediately all of Chung’s anxieties came roaring back. “I was absolutely shitting bricks,” he says. “I didn’t sleep for a week. All these anxious thoughts were coming into my head like, ‘What if you forget your lines and you’re doing your scene with Gary?’” He needn’t have worried. As Chung would discover, Oldman and Scott Thomas approach their craft with a confidence and, perhaps even more tellingly, a lightness that he hopes he can one day emulate. “They’re not serious about it,” he says. “Obviously they take their job very seriously, but we’re not saving lives. We’re not doing brain surgery. We’re not frontline workers. We get to do something that we love. I’m watching Gary every day on set. He’s always having fun. He’s always making me laugh right up until they say action.”

At the time of writing the buzz around Slow Horses was building. Will it launch Chung’s career? Who knows? This time around, he’s choosing not to spend too much time agonising over it. “I think the difference between 24-year-old me and 33-year-old me is that I’m just happy to work,” he says. “Thinking, What if this happens? Or, What if that happens? That’s anxiety talking. Those what-if questions don’t help you.”

In fact, Chung no longer believes in big breaks. Rather, there are steppingstones, no matter how far apart those stones might be. “There is no one breakthrough,” he says. “People that have these breakthrough moments have been at it for years. I think every break you get as an actor, whether it be doing panto, being a lead or being in a huge movie, everything is a break because you get to do what you love.”

Cutting Room Floor

When he’s not hustling in auditions, qualified PT Chung is crushing it in the gym. Use this workout to build a body that’s ready for ‘action’.

A. Superset: 5 x (6-8 reps)

Incline bench press

Front squats

B. Tri-set: 4 x (8-12 reps)

Split-squat with dumbbells

Single-arm dumbbell row

Skull crusher

C. Superset: 3 x (10-12 reps)

Seated shoulder press

Deadlift