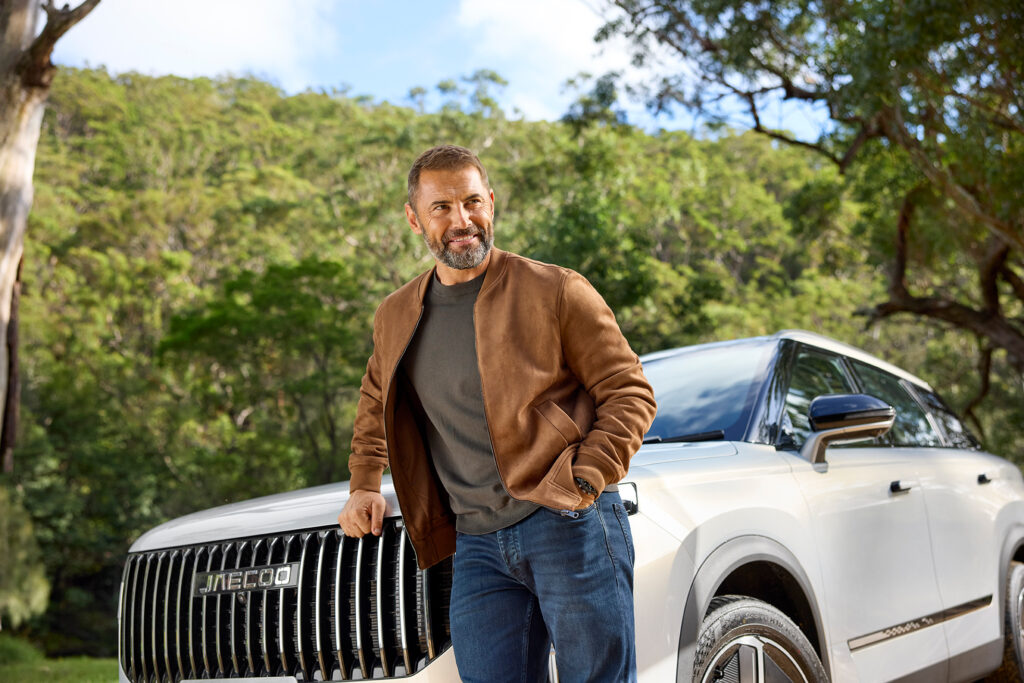

Commando Steve Willis, 45, is a father to four children ranging in age from five to 22. As he’s discovered, in order to become a better dad, you first have to deal with your own demons.

On being a young father

“I was 22 when Brianna, my eldest was born. She’s 22 now. It changed my life completely. I’d been in the Army for four years and at that age you’re full of beans. You want to go out there and conquer life. At the same time, my stepdad had drilled into us the importance of responsibility and accountability, so I was conscious of that, as much

as I had my own dreams and goals in life.

It’s challenging. You’re trying to make sense of what it means to be a man in the world and there are all these drivers pushing you, society saying do this, do that. You have to really get to know yourself, be comfortable in your own skin and love your child. They’re helpless, they need you, they need to be nurtured. Of course, that love is there, but you need to recognise it, tap into it and be willing to do anything and everything for that child. You hear about men not being willing to change nappies and that kind of thing. You have a responsibility, get it done. Don’t get bogged down in what others say about the drudgery, the whingeing and the whining. Have your own experiences.”

On discipline

“My stepdad was very, very strict. I think because of some of the things he got up to in life, he didn’t want us turning out like him. So, he was quite protective in a way that was almost controlling and we didn’t experience a lot. We were sheltered. The military was the same. You’re rubbing shoulders with people who are like-minded, very focused and again very disciplined and structured.

So, I was quite strict as a father and Brianna brings that up now. She’s like, ‘Dad, you’re so different now to how you were when I was younger’. It wasn’t until I left the military and I started to have more experiences and met people from different walks of life, that I started to realise there were other ways of doing things. I’ve softened now. I put a lot of space between things. I listen. I’m not so reactive and ready to jump on stuff. My presence as a man around my children is enough for them to just question what they’re doing. I don’t need to really raise my voice. They’re little human beings. With someone as big as me, just being present is enough for them to go, ‘Hey, hang on a second, I need to be a little more considered’.”

On exercise and family

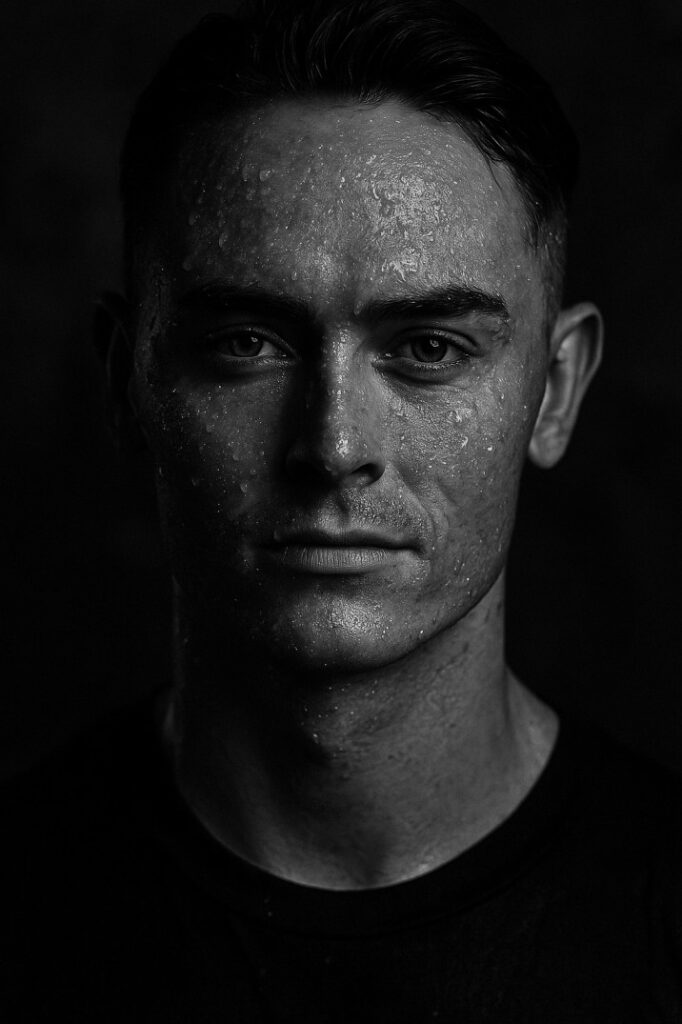

“My relationship with fitness when I was younger is a far cry from what it is today. I didn’t grow up being encouraged to express myself and talk about how I felt – many people didn’t back then. A lot of coping mechanisms that people turn to are often driven by the fact that they just don’t know how they’re feeling. So, they try to run away from themselves and throw themselves into things. I kind of did that with exercise.

I didn’t think too much of myself and I almost used a lot of the negative thought processes and the emotions that are born of those as fuel. I had a lot of anger, a lot of aggression and the military encourages that. Like you ain’t doing Kumbaya and hugging your enemy. It’s a service for the protection of the nation.

When Ella was born, I was in my early thirties and I’d left the military. I was working as a trainer and I was doing The Biggest Loser, while also competing in CrossFit. The level you need to be tuned in and focused, like laser-focused, on your training and nutrition to compete, is crazy. Every detail of your life needs to be on point. Of course, that’s going to impact your family and it did because lot of the time you don’t have much left to give.

Nowadays with exercise, my reasons for engaging with it and my relationship to it are completely different. I can derive joy and happiness from working out and just enjoying daily physical activity with the kids. Going out and throwing a Frisbee, going for a bushwalk or a bike ride and engaging with it that way. I’m not trying to win a competition all the time.”

On seeking help

“I really struggled with the profile that came with being on The Biggest Loser. It was kind of like, ‘Why me? I don’t deserve this’. It was a pressure-cooker atmosphere and I didn’t know how to get out of it. It’s really hard because a lot of us get bogged down when we’re reflecting on ourselves. There’s a lot of guilt, a lot of resentment. And when we’re not mindful and aware of that, everyone else starts to wear it. You’re just not a nice person to be around.

So, I sought help. No one really knew about it. One of the guys I saw gave me a book called Resilience: Hard-Won Wisdom For Living A Better Life by Eric Greitens. He’d been in the Navy Seals so straight away there was that connection. I absorbed every word in that book and what I really took away from it was that pain, suffering and fear are real, but they’re not unique.

That really helped me deal with where I was at, my responsibilities, the people I was accountable to and the things that happened that I wasn’t happy about. But I had to get to a place of acceptance. From there you can become a better person, have a better relationship with yourself, a better relationship with your partner and with your kids.

On parenting after a split.

A lot of people get to a point in a relationship where they realise that there are differences and you agree to disagree and go your separate ways. But you haven’t forgotten about your children. Axel spends time with me and he spends time with his mother and he’s got a fantastic life. The beauty of technology nowadays is that when we don’t see each other physically, we’ve got FaceTime. I’m on the phone to him or he calls me. My girls have their own phones, so there’s direct communication. And I do my utmost to be at events that they’ve got on, like school carnivals or if Axel’s playing football. You being a part of that builds to the bigger picture, because those are the experiences that they’re going to recall as they get older. They’ll remember, dad was around.

It was put to me so poignantly that when it comes to the adult/child relationship – especially when it’s different households – the parents have no rights. The children hold all the rights. And it’s our job to ensure that the rights of the children are upheld. They need our guidance, they need to see us as adults behaving a certain way and communicating in

a calm manner. It’s not always that way, but you do your best because they’ll be adults one day and parenting themselves. If they can see us doing that and we’re upholding their rights, then they’ll grow up to be much more well-rounded human beings.

Commando Steve is an ambassador for Karitane, leaders in parenting services. If you’re experiencing difficulties adjusting to fatherhood visit Karitane.com.au or call Karitane Careline on 1300 227 464