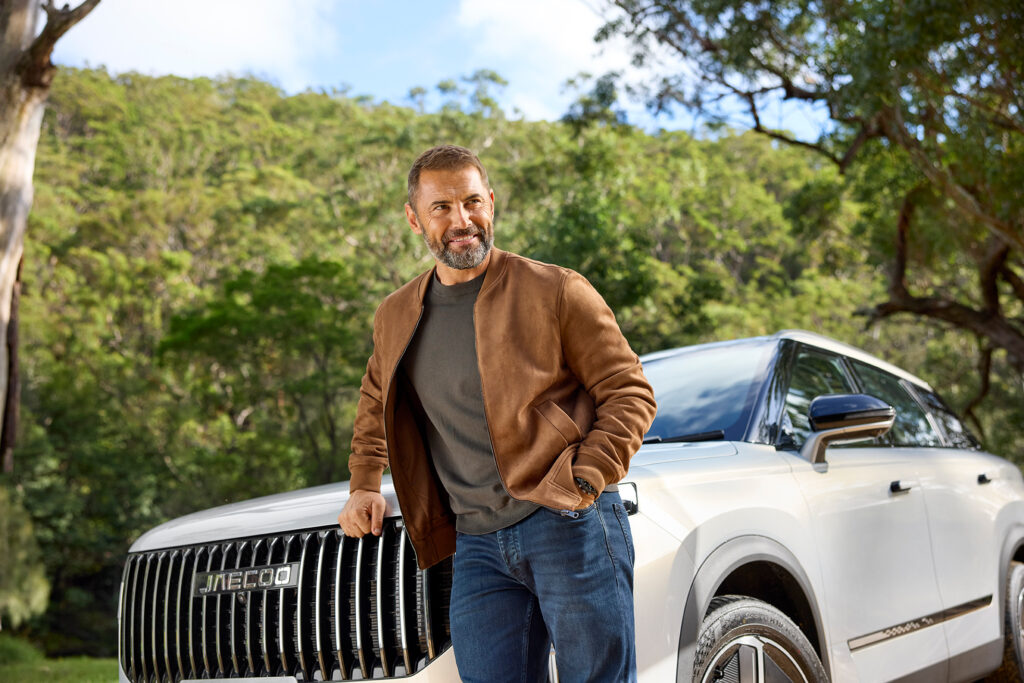

Ode to joy: James keogh, the humble man behind a big name star. Photography by Claudia Grosche.

A confession: without being overly familiar with the works of Vance Joy and not previously giving it too much thought, I had assumed that his stage name, an amalgam of two characters from Peter Carey’s novel, Bliss, was his real name. As such, I had a vague image in my mind’s eye of a modern troubadour, a larger-than-life character perhaps given to affectation and flamboyant dress.

What I find when James Keogh materialises on screen via a Zoom call from Barcelona, is a man without any conceits, airs or graces. Instead, I’m greeted by a friendly, humble and down-to-earth fellow who reminds me, both in appearance and in his air of thorough decency, of golfer Adam Scott.

Nursing a mug of black tea on a couch, Keogh’s curly hair is still damp from a shower and he wears the type of hiking fleece you might pull on after a run. He looks to me like the footy player or jobbing law clerk he might have been in a different life, not a folk singer or a pop star – and not one whose songs have racked up over 5 billion streams and who has toured with the likes of Taylor Swift and P!nk. You’d have to conclude that perhaps he needed that stage name.

For Keogh, Vance Joy was an attempt to draw a line between his professional and private lives. More simply, it was a name that just rolled off the tongue a little better than Keogh. But today, the boldness of the name he’s managed to wholly inhabit reminds him of a time when he wasn’t so sure of himself. A time when neither James Keogh, nor Vance Joy, meant much to anybody.

“I think I can be quite a shy person at times,” says the 34-year-old, who’s spent chunks of the past two years living in Spain with his girlfriend. “I remember being at the call centre where I was working during uni and people would be like, ‘Oh, so you said you play music?’ And they’re like, ‘What are you called?’ I was like, ‘Vance Joy’. And they’re like, ‘What?’ And you’re like, ‘Vance Joy’. And it’s like, that moment of someone not understanding, asking you again and then you get red in the face as you tell them. Especially when you’re starting out, before people know your music, you’re embarrassed about it. But I think the name felt right.”

It needed to. Success in the cutthroat, highly capricious world of pop music requires levels of grit, determination and sheer bloody-mindedness we more commonly associate with professional athletes or hard scrabble entrepreneurs.

“It can be unlikely even to pursue a career in music or to just keep persisting with it,” Keogh says. “I don’t know what that thing in your head you have to have is, but it’s almost like you’ve got to be blissfully ignorant of all the things that could go wrong or maybe that voice in your head that says, ‘You can’t do it’, has got to be a little bit quieter.”

Keogh? On his own, as himself, he might not have had it. He may not have been able to silence those doubts. As Vance Joy, though? There would be no limits to what he could achieve.

MASTER OF NONE

Keogh grew up in Murrumbeena in Melbourne’s east, where he and his mates owned the streets on their BMXs and rollerblades, hitting up the local milk bar and later, a McDonalds.

“It was like you have your little neighbourhood and you know all the shortcuts,” Keogh says. “It’s like a little dominion when you’re a kid.”

Keogh’s world would expand rapidly after he transferred from his local primary school to St Kevin’s College, a prestigious all-boys private school that competes in Victoria’s Associated Public Schools (APS) system in sports like Aussie Rules, cricket and rowing. Keogh would become school captain, a position he had secretly coveted since he was in Year 7, perhaps hinting at his vaulting, if largely hidden ambition.

“I was always fascinated by the school captain and the position, because every Monday he would speak at assembly where he’d tell a story and make it entertaining,” he recalls. “And when you’re a Year 7 kid looking up at him, you’re like, wow, this guy is a grown-up man. In that little world they’re the star. So, I was always aspiring to that. Even if it was a secret, I was thinking that was pretty cool.”

As well as an aspirational streak, Keogh’s ascension to the position also revealed his all-round abilities. He was the jock who was also friendly with the nerds and the musos. “I think there’s a sense that it has to be a guy that does a bit of everything,” he says. “Maybe you don’t have to be the best at sport, you don’t have to be the smartest guy, but you kind of have to be doing okay in every area.”

It would be footy at which Keogh would show the most early promise. He would make the school’s First 18, essentially granting him demi-god status within the school yard, though Keogh often found himself in awe of his own teammates. “It’s almost like the guys that were the best in those teams were heroes,” he laughs. “Even after all this time you go, ‘Geez, Antony Keely, Year 12, against Xavier, taking marks at full back’. Those people leave a big impression on you.”

Looking back, Keogh feels he was too often “in his head” to be a really consistent schoolboy player. “Maybe I’d have one or two games in the season where things clicked,” he says. “But it was almost like if the stars aligned and it just felt good that day. It was always a mystery to me why I played well.”

Typically, Keogh is probably downplaying his abilities. After school finished, he would play for the St Kevin’s Old Boys team before being recruited to the Coburg Tigers in the VFL, which at the time was Richmond FC’s reserves team. “I remember getting a call one day when I was in first-year uni and [coach] Andy Collins goes, ‘How do you feel about playing in the AFL?’ He planted the seed of that, and I was like, ‘Wow’. I didn’t have any idea what I was going to do. I was just studying and I wasn’t the most engaged student. Football was the thing I was most disciplined about. It gave me a bit of identity.”

Keogh took his first preseason with the Tigers seriously, getting in killer shape to contribute to a reserves team that won the premiership. The next year he started in the reserves before being elevated to the ones for the second half of the season, where he again played well. He describes himself as a dour defender who never wanted to draw too much attention to himself. “I remember I wore white boots to training one day and the captain was like, ‘Doesn’t feel right. It’s just not right for you’. And I was like, ‘Yeah, I know’.” As a footy player, it would appear Keogh had a bass player’s temperament.

In his third year he became complacent, he says, often finding himself dreading the weekends, not because he didn’t enjoy it but because of the cocktail of nerves and adrenaline that would rise throughout the week, reaching a crescendo on Saturday mornings. It’s similar, he says, to the nerves he still feels before a gig. “If I had a gig tonight and someone came in right now and said it was off, I’d be relieved,” he says. “But then it’s like, what do I do with all

this energy?”

His footy career would peter out. He knew he didn’t quite have it, didn’t want it badly enough, couldn’t turn down his inner voices. Not in footy, anyway. But if he was fading in one field, he was about to soar in another.

TOP OF THE POPS

Chances are you’ve heard Riptide. Even if you can’t immediately recall the tune or the words, the moment you hear Keogh strum the first few bars on the ukulele, you know it. It’s the kind of cosmic earworm that so thoroughly embeds itself in the collective consciousness you wonder if it has always been there. You almost forget someone had to create it out of nothing.

Encouraged by his father, Keogh had been playing guitar since he was a teenager. In the early days he didn’t put in a lot of effort, wagging lessons and essentially going through the motions. “I think my dad always knew, I guess from his own experience, that if I played guitar, I would have it for life,” Keogh says. “But when you’re 14, you don’t really take responsibility for anything. You think, ‘Oh, that will just fade away’.”

He became more enthusiastic when his dad organised lessons for him outside of school and bought him a Fender Squier Strat. He began jamming at lunchtimes with friends in the music room, murdering the latest Metallica riff or playing Green Day songs and changing the lyrics. After school finished, he and some of his more academically inclined mates, including the dux of the school, formed a band called Hypersonic. “I remember, across the board as a band, we all did really well in our English exams,” he laughs. “That didn’t necessarily make us the coolest band. I guess we sucked a little bit, but we did write a couple of good songs.”

Keogh was beginning to fall in love with the problem-solving dimension of songwriting, a feeling he’d previously experienced writing essays. “Sitting in that space of not knowing and trying to figure out if you do this with this, what happens? When you’re writing an essay for school or when you’re writing a song, it’s that same kind of jigsaw puzzle. It’s not necessarily fun, but if you find the enjoyment in that, then you might just get addicted to it.”

Keogh would study law at Monash, but while he finished his degree, the law certainly wasn’t calling him. He went through the motions of applying for summer clerkships, “just because everyone was doing it”, but he was far more excited about the handful of songs he’d written and begun to perform at open-mic nights.

Among them was Riptide, a song he’d first started writing while at uni in 2008 and thought, “this is nothing”, before returning to it a few years later. Looking back now, Keogh feels the song’s subsequent success lends its protracted creative process something of a mythical quality, like it was always meant to be. “Everything probably takes on a bit more significance because you link it all back with hindsight,” he says. “I remember being excited about it. It was the satisfaction you get from just cracking the code of a song. Just by putting the right word in the right place, without really thinking about it too hard, the song is created in front of you and you’re like, ‘Oh, how did I do that?’ It’s rare when that happens, but when it does, that’s the best thing.”

Keogh was working at the call centre and doing a bit of gardening work on the side and decided to use his earnings to pay for a day in the studio to record the song in 2012. He then put it on SoundCloud, like so many budding young songwriters do, many of them lucky to get more than a handful of listens. What happened next is the stuff of folklore. Hell, it’s basically a fairy tale.

“I put it on SoundCloud before having any experience in the music industry and knowing anyone or having a manager and it had like, a thousand listens after a week,” he recalls. My friend was like, ‘Dude, this is crazy’. I think you can gauge a song and the way it’s received pretty quickly, just from the people around you.” Later it would be uploaded on SoundCloud by record label Liberation and had 40,000 listens in a day. It would go on to claim the No.1 spot in the 2013 Hottest 100 and become the second-longest charting song in the US Billboard Hot 100 at 43 weeks. To date it has racked up over a billion streams, while being used by companies to push everything from insurance to automobiles.

Keogh’s career was put on a steep trajectory. Not surprisingly the sudden success left him reeling. “It’s hard to prepare for it,” he says. “Even if something like that happened again, it’d still be wild. But I think I’d probably enjoy it a bit more now, because I would have more context about how unlikely and rare it is to do.”

Indeed, the success of the song would create something of a rod for Keogh’s back. “I definitely felt pressure,” he says. “My first meeting at Atlantic Records, I went there to play a couple of songs for the top dog, Craig Kallman. And I remember he was like, ‘If we had a few more Riptides that would great too’. And I was like, how am I going to write one of those? I don’t even know how I did it. I’ll try.”

His goal, which continues to this day with the release of his third album, In Our Own Sweet Time, became to surround this towering hit with enough songs that can also stand on their own two feet. “They might not stand as tall and might not have the same impact as that song but that’s so out of my hands,” he says. At the same time, Keogh still has the drive to solve the puzzle again and capture that lightening in a bottle, even as he grapples with the confounding, sometimes ephemeral nature of songwriting. Like he said: it’s addictive. “I look at other artists like Ed Sheeran or Adele, and they really can do it again and again,” he says. “I’m always trying to get better. And sometimes I think, is it better to try more? Or just to relax and be a bit more Zen about it? I’m still a little bit mystified as to how it all works.”

INNER HARMONY

After our chat to today, Keogh will head out onto the streets of Barcelona to shoot some footage to accompany the new album, capturing some of the things he likes to do to unwind: ride bikes, shoot hoops, skateboard and read books. He began writing songs for the album in 2019 and continued through COVID, linking up with regular collaborator, Dave Bassett, who lives in California, on Zoom.

“The thing about doing it online is it’s much less impact on your body,” Keogh says. “Just less travel, but maybe you miss out on that little bit of magic of being in a new place, new sights and smells. But the songs still came. I always like writing from the perspective of hanging out with someone you care about and you’re in a timeless space where you forget about things and you’re really present in the moment. And I feel like that feeling kept showing up in most of the songs on this album.”

A film and book lover, Keogh likes to use movie dialogue to inspire lyrics, even bad movies. “You can get inspiration from any movie, it doesn’t have to be a serious movie,” he says, telling me he’s recently watched a lot of Adam Sandler films. “If you’ve got your antennas up, you end up catching these lines.”

You need to have your senses attuned in your personal life, too, he adds, though he often worries that he’s not doing enough. “You always think, are my senses prepped and ready? Am I really making the most of what’s available to me? I used to be trying to get everything down on my phone and then not let any of these voice memos slip through the cracks, because there’s probably 200 or more. I’m more relaxed about it now. I feel like the good ideas will come and promote themselves and stay in my head.”

Keogh’s diligence and commitment to his craft are revealing. While he remains uncertain about the exact alchemy of the songwriting process, it does seem there’s some mathematics – effort x volume – as well as magic going on. In that respect, it’s perhaps telling that when I ask him for his motto in life, he offers not some words of wisdom or metaphorical flourish befitting an acclaimed lyricist, but instead falls back on the most utilitarian of aphorisms: just keep chipping away. “People would often say, ‘What are you doing?’ And I’d be like, ‘I’m just chipping away’. It was a way of deflecting, but also just keeping disciplined and controlling the things that are in front of you. It can be hard some days. Maybe you feel like you’re not doing good or you did something you’re not so proud of. Maybe a song isn’t doing as much as I wanted it to, but it’s just like, the next thing you do, whatever it is, you’ll have an opportunity to do something great. So, just keep chipping away.”

I’m not sure about you, but to me, that’s not something I can imagine a bloke called Vance Joy saying.