1.

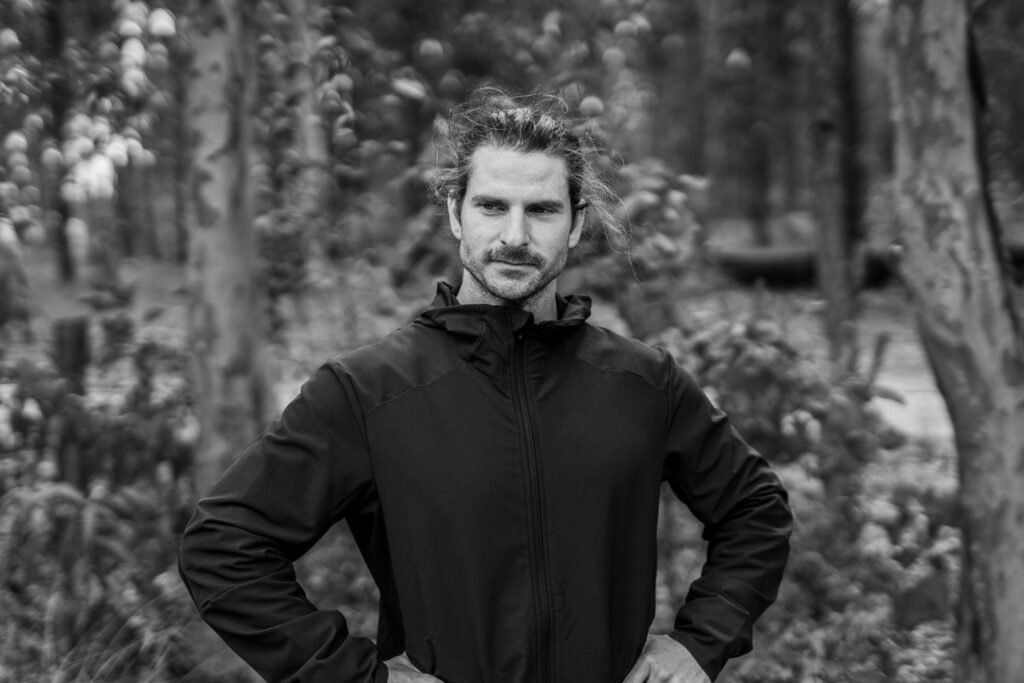

On this Friday where spontaneity and chance must be strangled by tight schedules and routine, nothing is going to plan. For starters, there’s the car, which isn’t so much a car as it is an all-purpose weather vehicle promising salvation for Dan Price and his support crew. That car is now bogged somewhere in Barrington Tops National Park. Dan had driven there on the Thursday morning, hoping to do a quick assessment of the last checkpoint on his route. What was meant to be a scenic drive through bush trails and the kind of crisp mountain air that electrocutes the nostrils was instead a terrifying ordeal in off-roading. He could feel the tyres sliding out from underneath him and when it became clear that no amount of acceleration would get the car unstuck, Dan reached for his phone. No reception. Classic stitch up.

His coach had told him to take it easy, to stay off his feet and keep walking to a minimum ahead of Friday. To be knee-deep in mud, using the weight of his entire body to push a four-wheel drive out of the bush is less than ideal. So Dan hiked out of there, found a farm, and asked people for help. It was of little use. The car had to be abandoned and by the time Dan made it to Hawks Nest it was already 9pm. He hadn’t eaten anything and still had to prep his gear and food, things that needed to be dry were now mud-stained, and the greater part of five months of training were unravelling in an instant. Talk of postponing the endeavour began to circulate around camp but for Dan, the day’s events had merely strengthened his resolve towards what would be his most challenging run to date: Project 205, an attempt to run 205 kilometres over some 7000 metres of elevation in under 40 hours. Nothing was going to plan, but Dan knew he was up for the challenge.

He’s three hours behind schedule by the time he starts, and the delay means temperatures are already climbing into the thirties. The humidity hangs low, covering the landscape in a hot mist that makes perspiration immediate. Dan thought he’d be cruising. He’d envisioned a relatively flat start that would conserve energy and make for an efficient pace, but shallow flooding had turned the trail into an uninviting marsh, a breeding ground for blisters and wrinkled skin held captive in sweat-soaked socks. With the five kilometres of soft sand that greeted him upon setting out, his quads are already protesting the strain and for the first time in a long while, Dan is terrified. He shouldn’t be hurting like this; not this much, and certainly not this early.

To anyone observing Dan’s effort and the grimace distorting his features, a culprit for such suffering needs to be found – and here there are many. The elevation, trail conditions, the emotions that threaten to rattle Dan off-course. It’s a choose-your-fighter epic in which Dan is powerless to the forces at play. But to think the universe is conspiring against him is to be proven wrong. That Dan is living is a statistical anomaly. That he survived two suicide attempts defies all data. Every first impression made from that moment to now is meaningful, every morning an opportunity. It’s the idea of discarding the calendar, of throwing out the clocks and those arbitrary markers in which we look for all significance and meaning. It’s the internal monologue that says we can start again tomorrow; just another ordinary day. But a day that presents itself as a gift, because here you are, living.

When he comes through the first checkpoint at 38 kilometres, the pain is visible. He should have been taking in the calories that are stuffed in his various pockets in gel form, but in an effort to make up for lost time, Dan missed those eating cues. Weary and slightly nauseous, he sees his support crew up ahead and before his body can crumple into a folding chair, there’s a familiar voice. It’s the sound of his daughter, Talulah, reaching out for her dad and pulling him into comfort. There’s an embrace. There are tears. And while Dan is quick to check if Talulah is OK, it becomes clear that love is the cause of it. “Yeah, I really love you,” she says, arms tightening around Dan’s neck.

A part of Dan breaks exiting that checkpoint. As the voices of Talulah and his family are soon drowned out by his own heavy breathing, each step wedges a greater distance between the next embrace. Where our internal monologue can be steamrolled by doubt and negativity, it’s Talulah’s that Dan never has to strain to hear. Hers is the voice that tells him to keep going and push past the suffering. Dan hears Talulah and he knows why he’s doing this. He knows that it’s not about the accumulating miles underfoot or the run itself. Dan sees his family and therein lies his purpose: he wants to see his son and daughter grow up, he wants them to be able to speak openly about their emotional and mental health, he wants them to be able to do so without any feeling of shame attached to it. More importantly, he wants them to see in his example that there is so much life to be lived on the other side of mental illness. And so Dan runs on.

2.

Not long ago, over the course of his daughter’s first birthday, Dan checked into The Sydney Clinic in Bronte. He was overworked and burnt out, having allowed training and exercise to take a backseat to the pressures of providing for a family. But mainly, Dan was a father grieving. He and his partner, Sarah, had just suffered a mid-term miscarriage and while it’s hard to imagine losing a child, it’s harder still to imagine being robbed of such a loss. The idea that pregnancy can only be revealed after the first trimester is to suggest love is dependent on time; that months, years, even decades must elapse for memories to stockpile and lodge between the softest nerves. To subscribe to this notion is to ignore the love that is instantaneous and all-encompassing, the love that begins with two lines on a stick and a future that unfolds with the sound of a heartbeat. You may lose a baby, but where does the love go?

Even now, with the distance of time, tears are quick to rise to the surface. “Life was hard. People don’t talk about miscarriage and how fucking hard it is. You don’t tell anyone until sixteen weeks, so then if you have a miscarriage at fourteen weeks, no-one knows?” Head in his hands, Dan utters an apology for a reaction that speaks to the love that never left him, “You’ve heard the baby’s heartbeat. That’s a real baby, you’ve probably named it. And that’s what happened to us.”

Dan defaulted to the mentality of needing to be the man of the house; that is, a man wearing a mask so as to disguise his pain. He began feeling “a little bit suicidal” and while the thoughts scared him, experience meant he knew what they were and so he knew he needed help to break free of them. When Dan finally met with his psychologist, his mental health was deteriorating rapidly. He remembers that conversation though, because it’s frequently one he reminds himself. “I said to her, ‘I can’t go in, my daughter’s turning one next week.’” His psychologist replied: “Dan, if you don’t do it, she might not have a dad.”

In the clinic, Dan went back on medication to assist with his mental health, but he also had a conversation that would steer him towards the thing that saw him reclaim his identity. When asked what excited him, Dan struggled to find an answer. His identity was so firmly bound up in work and family commitments that he couldn’t articulate anything that felt like Dan; Dan in the singular, Dan that pursued activities and hobbies with the sole intention of stoking the internal fire within. It was then he realised he was also mourning the loss of team sports. As a kid, he was rambunctious with a seemingly limitless energy reserve. But when he was diagnosed with ADHD at seven, he found himself cast as an outsider. He struggled to make sense of his own mental illness and was picked on and bullied at school. Though the medication helped, it reinforced in Dan the understanding that he was different to his peers. Where the classroom felt like a cage, sport granted Dan the freedom to be the full expression of himself. A naturally gifted athlete, everyone wanted him on their team. His presence was synonymous with high-energy, skill and that unwavering loyalty solidified in fist bumps and tactical whispers. Dan found an acceptance on the sporting field that had eluded him throughout school and when career got in the way of this, he lost those connections. “What about joining a run club?” suggested his doctor. And so, on the first Saturday of November following his stay at the clinic, Dan went down to Bronte Beach to see what was so great about this thing called running.

3.

Before the sun can commence its commute skyward, members of the 440 Run Club assemble along the foreshore of Bronte Beach. Dan arrived just before 4.40am. It wasn’t so much that he was nervous as it was him wanting to suss it out from afar. He wanted to get a feel for the vibe, you know? That elusive feeling that has the capacity to drain all enthusiasm quicker than Snapchat to an iPhone battery. While run clubs have come to populate nearly every suburb in recent years, promising their own aesthetic and ideas for socialisation, the enduring image tends to be that of the elderly with a new lease for life, or semi-professionals decked out in Nike with eyes firmly glued to their Garmins, yelling obscenities at anyone who dares see them divert from the inside lane of the track. Looking back on that first run, Dan is quick to admit his reticence. “I went there thinking, ‘I don’t want new friends,’ and what ended up happening was I met this whole bunch of new, amazing people who wanted to just meet other people,” he explains.

With its 5am start, the 440 Run Club breeds a certain kind of lifestyle in those willing to trade a warm bed for an early start. After-work drinks on the Friday are replaced with a night-in and when Saturday rolls around, you’ve completed the run and taken a dip in the ocean before most have even had time to rub crumbs of sleep from their eyelids. The 440 Run Club is as much about running as it is about conversation and the connections forged in the absence of booze and small-talk. “I was searching for the simple life and not having to drink to socialise and it was this idea of one door closing and another opening. I realised I could kind of let some friends go,” says Dan, using air-quotes to describe those so-called mates he only ever drunk and partied with.“It was never really about the running.”

During those runs along Bronte Beach, Dan found community. He found the connections he’d been missing from his days on the sports field and, more importantly, he’d found a place he belonged. Those early morning runs were for his daughter, but they were also for himself. Dan arose and in putting foot to bitumen and soft sand, he found something sacred, a ritual that began under the blanket of darkness and finished with sunrise. Running was the thing that lifted Dan into the day. At first the runs were short and slow but even as distances increased, the intention was never about recognition or reward. Here was Dan, doing something for himself, and that something also made him a better person in the process: a better father, a better partner, a better friend. He knew he was never going to win running races and a life dictated by the competitive calendar was far from appealing. Dan simply wanted to test his own limits while using running as a form of therapy and a safe space for others to share their own struggles. “Running is a language for me,” he explains. “I feel like it’s almost my ability to communicate and express myself at the moment. It feels really powerful to be able to speak to people through my running.”

Before Dan could hold space for others though, he needed to carve out space for himself. Before Dan could become the person he wanted to be, he had to let go of the person he was: the guy who survived suicide.

4.

In 2014, Dan believed it was a reasonable idea to take his own life. He was only 29-years-old, but life’s experiences seemed to suggest it was time. Outwardly, Dan still presented as a highly successful individual. His was still the charismatic buoyancy you’d expect of a keynote speaker at a TEDx conference. After receiving a scholarship to work at an international property firm while at university, Dan found himself drawn to corporate culture. Before him lay a roadmap of organised meetings, monetised incentives and a clear-cut trajectory that rewarded those who wore the phrase “too busy” like a badge of honour. Dan excelled. He was promoted three times in the first four years and soon became the youngest ever associate director at his firm. At 23, he was married; he had the cars, the house, the flashy suits and expensive timepiece to match. But with each promotion, the reward came to be overshadowed by a target that loomed even greater and at 28, Dan found himself in marriage counselling trying desperately to resuscitate a relationship that had long gone cold.

Love doesn’t exist without loss. Perhaps what elevates it to the euphoric state so many of us seek to inhabit is its ability to be taken from us; to love someone is to embrace that risk, understanding that those shared rituals and routines will one day become an experience coloured by their absence. Dan’s divorce was an implosion of his carefully curated vision of success and the sense of failure was instantaneous. His entire character was suddenly called into question: What is success if it’s not shared? How do you live life as a good person when you’ve broken the most sacred of promises? How do you rebuild after losing the connection that proved most formative?

He moved back home with his parents and there, in his old bedroom, depression hijacked his thoughts. Each morning became an exercise in corporate cosplay, an elaborate act of suiting up as Dan wondered how he was going to fake the day. At the office, he began having panic attacks and at home he was drinking heavily. Friends thought he was just blowing off steam and returning to life as a single bachelor. He didn’t know how to tell them he was hurting, or how to convey the extent of his loss, especially when he could barely admit it to himself. When he reflects on that period of his life, Dan recalls feeling completely broken. “It comes to the point where you rationalise the thought and it makes sense, your mind just completely turns against you and it starts to become a thought that isn’t even scary,” he explains. “It’s just like, ‘maybe this world isn’t for me anymore’.”

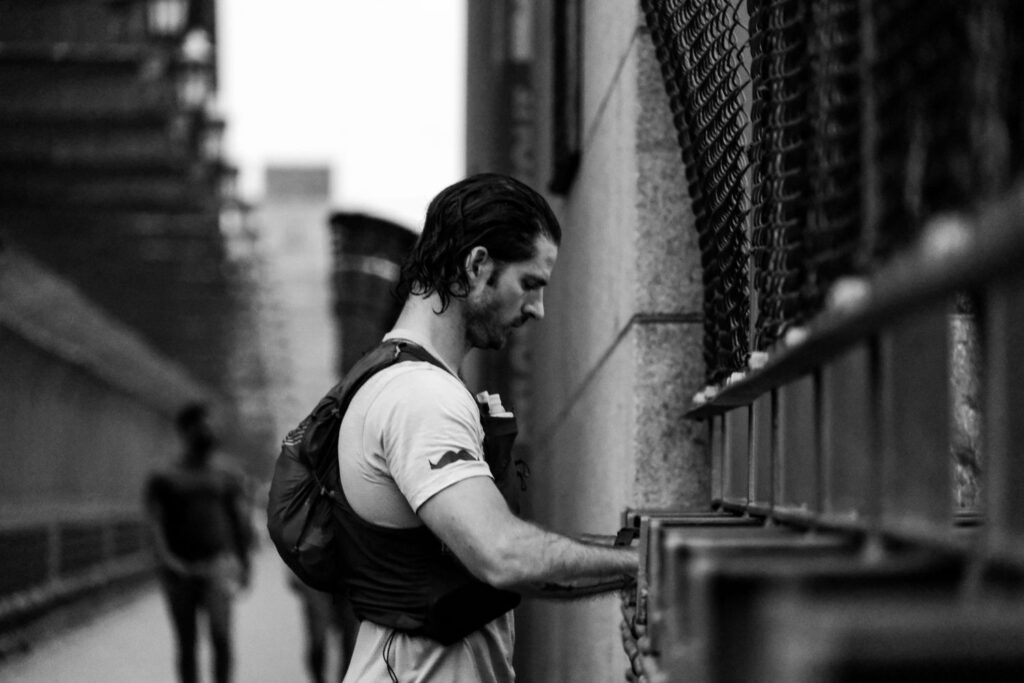

As the sun rose on the morning of December 4, Dan climbed atop the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Dangling over the safety fence, he took off the watch his younger brother had so often admired and sat it next to him on the thin railing. I’ll leave it there for him. As he stood there, justifying his desire to take his own life, a security guard noticed him. Traffic was grid-locked for hours. Cars full of wailing toddlers, impatient workers en route to the office, mothers stressing about the school drop-off; all of them ignorant to the fact police were making a desperate plea to stop Dan from jumping. The conversation that transpired on the bridge was the first time Dan articulated his depression. When he finally admitted those feelings aloud, his mental health journey began. “I never wanted to tell my mates, ‘I hate myself. I drink myself to sleep. I want to kill myself,’” Dan says. “I didn’t know that you could talk about that. I thought that I was the only person in the world feeling it and that everyone would turn their back on me if I told them.”

It’s an attitude Dr Kieran Kennedy is all too familiar with in his line of work as a psychiatric doctor and specialist in men’s health. On average, one in eight men will experience depression and one in five men will experience anxiety at some stage of their lives. Each year, over 65,000 Australians make a suicide attempt but the data presents an overwhelming gender disparity. Suicide is the leading cause of death for men aged 18-44 in most countries around the globe. As the Australian Bureau of Statistics reports, of the 3,318 suicides in 2019, 75 per cent were men. “I’m talking more than car accidents, more than cancer, more than heart disease or any other cause of death,” Dr Kennedy says, referring to the statistics that show we lose an average of nine people every single day to suicide in Australia, with seven of these nine being men. Much like Dan articulated a feeling of isolation, Dr Kennedy explains social conditioning has contributed to what is now regarded to be a silent epidemic, “elements of stigma, stereotyping and shame have not only kept men themselves quiet about these struggles and losses, but kept our communities in the dark about how huge the problem is too.”

Dan only experienced this stigma following his suicide attempt. Until his crisis point and ending up in hospital, he’d never sat in on a mental health presentation, be it in school or the workplace. And so he didn’t know that those behaviours and suppressed emotions were an indicator of something else; he didn’t know there were people and organisations out there he could turn to for help. His workplace handled his absence by telling colleagues he was merely on extended leave due to his divorce, fearing the reality was too much for people to hear. No-one came to visit Dan in the hospital because no-one knew he was there. “We can’t keep silent on this anymore or keep losing so many lives behind those closed doors,” Dr Kennedy says. “Suicide in men is absolutely an epidemic, and in many age groups it takes more lives than any other cause – but to change that, we’ve got to knock back the silence, we’ve got to light up that dark and get talking.”

Dan wanted to light up the dark. From his experience with the 440 Run Club, he knew running could also get people talking. As he came to be more involved with causes like Movember and an advocate for men’s mental health, he wanted to unite his two passions and in 2020, it led to The Long Run. It was a pilgrimage that would see Dan and his mate, Lockie Clancy, run three marathons back-to-back from Bondi Beach to Palm Beach and back, to total a staggering 126.6 kilometres. Dan had hardly cut his teeth in the ultra-running scene; at this point his longest run had been 60 kilometres. But having experienced rock bottom in such dramatic fashion, he knew that the voluntary suffering of an ultra-marathon was nothing compared to the emotional pain inhabited daily by someone in the throes of depression. As word of the endeavour spread, more people began joining Dan on his training runs. He’d post the route and starting time and there strangers would gather, looking for nothing more than the promise of shared miles. “Random people would show up and just download their life story or what they’re going through. Quite often it was the first time they’d spoken to someone and then I’d encourage them to see a therapist,” Dan says. A smile widens across his face at he recalls those months of training. “It was a gift.”

The day before taking off for The Long Run, Dan and Lockie’s phones lit up with messages from loved ones, family and friends, all of them bearing the same tone of warning. A heat wave was descending upon Sydney, set to push temperatures into the mid-40s and see the arctic chill of the 7-Eleven air-conditioning become a haven for those caught outdoors. Dan and Lockie took off at 4am, distinguished only by the beam of their head torch dancing along the foreshore. By midday their salt-stained shirts clung to their torsos like cling-wrap. In a testament to the power of Dan’s cause, countless people gathered along the route to cheer the pair on. To have been there was to see faith in humanity restored: strangers holding out Gatorade and iced water, lollies available by the handful and oranges sliced for ease of consumption. Many even braved the heat and ran portions of the run alongside the pair, experiencing their first marathon or ultra-marathon, and in some instances even running a personal best. The sense of accomplishment was a shared one and after ticking over their second marathon at 84 kilometres, Dan and Lockie had no shame in making the call to stop. The prospect of ending up on a drip in hospital was looking unavoidable.

While still recovering from the dull but persistent ache of tired legs, Lockie received a text from Dan: “Man, I really want to go out there and see if I can finish this thing.” At first Lockie thought he meant just doing the last marathon, a way of tying up loose ends to a memorable experience. But Dan wanted to do what they had first intended: to run a triple marathon. Just four days later, the pair met up at the same start point at Bondi at 3am. They hadn’t told anyone, but morning light soon came to expose their plans and it became clear to Dan that while he was running for those whose lives were lost to suicide, he was also running for himself. In completing the full distance, he ran over the Harbour Bridge, to that place he had once stood, all too ready to take his life. Looking out across the harbour, Dan stopped. He pulled out the journal entry he’d stuffed between the plastic of his phone case; an entry he’d written during his stay at The Sydney Clinic following the miscarriage.

You are not your past. It was never your fault. Believe you deserve all of this. Surrender now; breathe. Breathe. Let go. Say farewell to the old Dan. Stop holding onto him. Stop carrying him around with you. He makes your soul too heavy. You are just Dan. You aren’t the guy that only survived suicide. You are so much more.

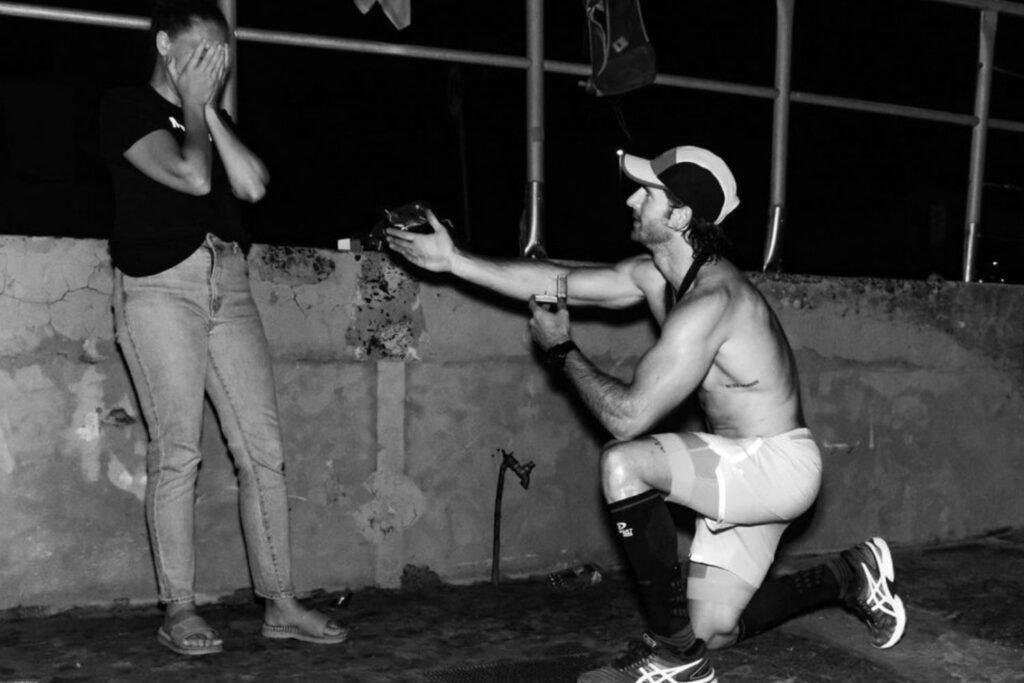

In a ceremony of forgiveness, Dan recited those words and felt those dark years fall from his shoulder like sweat off his brow. The guilt and the shame drained from him and when he resumed the run, he had the acute awareness that he was running towards home. After five marathons in five days and a stride clipped by fatigue, he and Lockie made it to Bondi beach and there, waiting for him amidst a sea of people, was Sarah and little Talulah, and the even smaller Sunny, their newborn son. Dan was always more than a statistical anomaly but it was only in the completion of The Long Run that he felt free to be the man he wanted to be, to show up as a fuller expression of himself. With a stiff-legged stagger he walked over to Sarah, took her hand, and dropped to one knee.

5.

50 kilometres into Project 205 and the red dot on the tracking device had slowed to a crawl. Having entered a significant calorie deficit, Dan’s body was shutting down. His stomach began cramping and the idea of force-feeding a gel with all its sticky sweetness only made him more nauseous. So he began problem-solving. He reached for the baked potatoes he had stored in a pocket, allowed his mouth to curl around one and let the pale-yellow flesh dissolve on his tongue. It stayed down. He swallowed his pride and began walking the next part of the run, allowing his increasingly erratic heart rate to slow. When he then cruised into the aid station at 80 kilometres, his support crew stood with wild, searching eyes. It seemed those in his camp had forgotten – even if only momentarily – that this was a man who knew what it was like to experience the depths of despair, a man who also knew that it’s possible to get out of it if you can just hang on long enough.

It’s there that Dan starts to feel good. He eats hot noodles and a kind of miso soup, savouring the saltiness. Worries about running through the night on a trail he was largely unfamiliar with had plagued him for much of the day, but in turning things around he now felt only that childlike sense of enthusiasm where fears are never so great to rival curiosity and perceived invincibility. The moon is obliterated by the beam of a head torch and with his mate, Tom, running alongside him, Dan finds the ever-elusive flow-state. The pair move as if tied by string, their footsteps quick and light, mirroring each other stride-for-stride, arm-swings one continuous pendulum.

When morning arrives, Dan’s been moving for 24 hours and his inexperience in ultra-running is beginning to show. Unable to quiet his thoughts, he didn’t nap when he was encouraged to at the 135 kilometre checkpoint. He’s unable to make rational decisions or study the map and mistakes have already been made on the trail, resulting in an additional five kilometres being added to one section. As he runs into the checkpoint at 162 kilometres, Dan has just one 40-odd kilometre leg left to go. Taking him along the Ridgeline, the vertical ascent reaches some 1500 metres above sea-level where the air cuts through all base layers and pierces the bone. The most remote point of the route, it grants no access for crew members or a support vehicle to follow behind. The only advice Dan had received was from a National Parks representative: “Don’t get stuck out there, or we’ll have to get a chopper to come rescue you.”

Dan surveys his surroundings. He allows himself to take in the 162 kilometres he’s just run and the people standing around him, listening to his every request and doing what they can to support him. He thinks of Sarah and his two kids. He imagines them watching that red dot head into the final unknown where so much can go wrong “I feel like…maybe,” begins Dan. “I feel like I’ve done enough.”

Dan hears himself speak the words before he fully acknowledges their meaning. Jase Cronshaw, crew chief and Dan’s voice of reason, walks over to where he’s sitting, head bowed over a pot of noodles, and the two begin to talk. They talk about Dan’s purpose and what connects with him. They talk about those things we want to disassociate from – the Strava posts, Instagram, the comments of strangers that amplify every negative thought we’ve ever held of ourselves. They talk about that first 50 kilometres where it seemed like he’d never make it to 60km. And they talk about Dan now; the Dan who is living, the Dan who is healthy and gets to return to Sarah and the kids in one piece. And they talk about how that alone is enough for Dan.

6.

Three months have elapsed since Project 205 and yet when we talk, it’s clear that making the decision not to continue is still something of a flesh wound for Dan. It’s not a disappointment or sadness that colours his voice, but rather a tender curiosity that remains. If The Long Run was a pilgrimage of forgiveness, Project 205 served as a question, an unticked box that lingers somewhere within the sinews of Dan’s musculoskeletal system. Sport so often favours the victorious with snapshot podium finishes that come to be burned on the retina. But when it comes to the losses and perceived failures, these are the moments that prove most human.

That Dan did not finish Project 205 speaks to the man he is now and the one he always wanted to become. “Especially being a bloke, society expects us to push and push and push. It’s a real masculine, bravado thing to do to just bury yourself,” he explains. “It’s celebrated. Think of road racing: if you finish a half-marathon or marathon and you collapse over the finish line and you’re dehydrated and vomiting, everyone’s like, ‘you’re a beast! Fuck, you buried yourself mate, well done.’ I had to take all of that away, everything society’s taught me in years of sport and racing; about needing to win and needing to succeed and to finish things. I had to let go of all of that in that moment to make the decision.”

The easier decision would have been to stomach the noodles and trudge on through the morning, only to keel over at the finish line with muscles that ache like a bruise when touched. But the run was never about Dan. When it comes to his purpose, the finish line looms always out of sight. In turning to go back down the mountain to where his family and friends waited, Dan proved that sometimes you give it all you can on any given day, and sometimes even then you’ll fall short. “You can set yourself really big goals, goals that you think are potentially just out of reach, but that’s when you really get the best out of yourself,” he says. “I wanted something so hard that I didn’t know if I could finish it.”

At 29, Dan never could have imagined his life being as fulfilling as it is now aged 36. He never thought he’d experience a love as deep as that which he shares with Sarah, or that newfound purpose condensed in the wide eyes of a newborn, but he held on long enough to find out. He sees Talulah and Sunny and knows there’s still much to be done in removing the stigma associated with mental health and suicide, and that his long runs are just a small part of bringing those conversations to life. But each morning when he laces up his sneakers, Talulah turns to him and asks, “Oh daddy, are you going running in the bush?” He nods enthusiastically and she replies, “Are you running for all the men who are sad? Are you going to help them feel happy?”

And Dan runs on.

You can follow more of Dan’s journey and running endeavours here. Dan is also an ambassador for Movember and R U OK?.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide or self-harm, help and support is available. Call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or text 0477 131 114 for 24/7 support where you can access confidential one-to-one text with a trained Lifeline crisis supporter.