Image: Shutterstock.

Stepping up to the podium this past August, where he was about to announce that he was leaving his beloved F. C. Barcelona, the only club he’d ever played for, soccer legend Lionel Messi took off his mask to reveal a face in mid-weep. As his wife and children, his teammates, the media and millions of people watching the livestream looked on, Messi’s brain hijacked a carefully staged farewell event. Leo wept.

For Messi, it – likely some combination of the memories, the hopes for the future, the people in the room, the city – was literally too much. So his brain went into action. His amygdala, the brain’s emotional centre, sent a powerful set of signals to his hypothalamus, the pea-sized structure responsible for maintaining stability during times of stress. That then activated the branch of the autonomic nervous system responsible for the body’s response to all of this. The parasympathetic nervous system and Messi’s tear ducts engaged, and it was all over.

For two minutes, lacrimal fluid streamed from his eyes as he approached and retreated from the lectern. It flooded his sinuses and flowed out his nose. (That’s not snot – it’s tears.)

Although he said no words, the message to his fellow Homo sapiens was clear: he was overwhelmed.

Many of us were taught to see crying as weak, small, pathetic – that it somehow minimises us. But think about it like this: crying is the fullest emotional expression.

It takes your whole brain to produce it and your whole body – your wet eyes, your runny nose, your slumped shoulders, your vocalisations – to carry it out. When we cry, we’re sending an undeniable and unmistakable message that men rarely send: we’re overwhelmed. We have too much.

Crying is – well, it’s a lot.

We’re not smaller when we cry. We’re bigger. And more whole.

What Crying Does for Us

There’s no clear evidence that crying has many psychological or physiological benefits. One of the most recent studies on the benefits of crying isn’t all that compelling. Researchers predicted that participants who cried might be able to withstand a stressful task longer or recover from the initial stressor faster than those who didn’t cry. The research suggested merely that your heart rate decelerates just before crying and that it returns to normal while you’re doing it – that’s your autonomic nervous system keeping things stable.

Some scientists suggest that crying – sobbing especially – can be cathartic because taking in big breaths might increase activity in the parasympathetic nervous system. But their assertions are always peppered with “might” and “seem”. We know more about how animals express distress than how humans do.

Bottom line: there’s just not a lot to back up the idea that crying makes our bodies work or feel better. Psychologically and socially it can, but perhaps a greater benefit can come if you listen to what it’s telling you.

And it might make us feel worse. Not all crying is good. Breaking down in a tough meeting at work can lead to feelings of embarrassment, even if it reinforces your humanity to your colleagues.

One thing we do know, however, is that when you cry, your body is engaging in one of the most elemental human responses to stress – something you were doing from literally the first few seconds after you were born.

For Philip Gable, a University of Delaware professor focused on how emotions influence our thoughts, crying is not all that different from any other expression of emotion. “There’s no sadness centre of the brain. Some types of sadness may activate certain centres, but we’re really whole-brain people. So when you have an emotional experience, it’s largely activating huge areas in the brain.”

You may cry. You may smile. You may cry and smile at the same time. Emotions are expressed because they are overwhelming the brain.

Women seem to be better at this type of expression. At least they engage in it more frequently, as numerous studies have found. Researchers aren’t sure why. It might be explained by hormones, in that testosterone might inhibit crying. (Some researchers think there may be a simpler explanation: women have shallower tear ducts. They simply fill up faster.)

Gender aside, who cries and when may depend on the culture you’re in. In a 2011 study, researchers found that “individuals living in more affluent, democratic, extroverted and individualistic countries tend to report to cry more often”. However, the difference lies not in suffering but in freedom of expression. In cultures where tearfulness is less common, crying seems to be connected to distress. In countries like the United States, where it’s more common, crying seems to be an indicator of personality and expressiveness. For instance, the tears that Barack Obama shed at various times in his presidency – from listening to Aretha Franklin sing at the Kennedy Center Honors in 2015 to speaking about gun control in 2016 – were widely seen as signs of emotional depth rather than helplessness.

What Crying Does for Our Relationships

As a group of researchers put it in their 2018 paper in Clinical Autonomic Research: “Until recently the focus has been on the intrapersonal effects of this behaviour (i.e., the effects of crying on the crying individual him- or herself). However, research strongly suggests that the possible mood benefits of crying for the crier depend to a great extent on how observers react to the tears”.

Humans are very good at masking our feelings, until we’re not. Tears are the ultimate tell. Unless you’re an actor, you have a hard time producing tears. It requires real feeling to do that.

And that’s a powerful message, says Gable. “There are thousands of languages all over the planet, but we have very few emotional expression differences . . . Crying [is] a way of expressing how we’re feeling more clearly than words ever could.”

The subtext is “I need help”, and we’re generally wired to help. Tearful expression of emotion tends to elicit powerful feelings that compel us to console. For the crier, that means an opportunity to embrace (and identify) not only the emotions that trigger the tears but also the sympathy, kindness and closeness they invite.

This isn’t always the case, of course. “If we know there are cultural restrictions or stereotypical beliefs or people we really love who we know just won’t get it, there are still places where it is more acceptable – like on a therapist’s couch,” says psychiatrist Gregory Scott Brown. “One of my first therapy patients would not allow himself to cry around his wife, because it made her feel uncomfortable. But he did allow himself to cry around me, and that made him feel better. I see that a lot with my male patients.”

You’ll be skipping the social benefits if you cry alone – or in a place where it goes undetected – but that’s probably better than repressing tears when you have them, Brown says. “I’ve cried many times during yoga class – it’s hot, dark and sweaty. When they brighten the lights at the end, no one knows, and I always feel better.”

How to Cry

And what if you’re cry resistant? Researchers don’t know why some people tend to cry and some people don’t. Could be social stigma. Could be hormones. Perhaps you just find something like talking more useful.

It’s such a fundamental expression of emotion that there may not be a way to get “better” at crying, though you can certainly create optimal conditions for it. The important thing is not really the crying. What’s important is paying attention to what you’re feeling whenever you show emotion, however you show it.

But let’s try to cry anyway. Here’s an activity. Go watch the end of Toy Story 3 right now. Field of Dreams could also work. Maybe that Apple commercial where the old farmer finds his iPhone in a haystack. (Take your time – we’ll find some Kleenex.)

Cry.

Just let go.

Note that it’s not the music or images that are making you cry. They’re just triggers for emotions that your brain might not know how to express linguistically.

Next try to understand what made you weep. Men’s Health has talked to a lot of therapists over the years, and one thing they consistently say is that for many people, especially men, the challenge

is not in identifying emotions – it’s in identifying that you’re even experiencing an emotion. Crying requires you to acknowledge you’re feeling something. It forces you to confront that reality. No emotion, no cry.

Now take it a step further. Are you feeling sad or happy or angry? Whom are you thinking about? A relative? A friend? A traumatic moment in your life? Crying doesn’t offer many clues. Crying is simpler than that. It’s up to us to figure out the why. What an opportunity.

Just Let Go

Meet the guys helping to mainstream crying in public.

Lionel Messi

At the press conference announcing his departure from Barcelona, the club he’d played for since age 13, the soccer icon shed tears like he normally sheds defenders.

Prince Harry

The woke-ish royal is not a fan of the stiff upper lip, welling up at his wedding and when discussing what it means to be a parent.

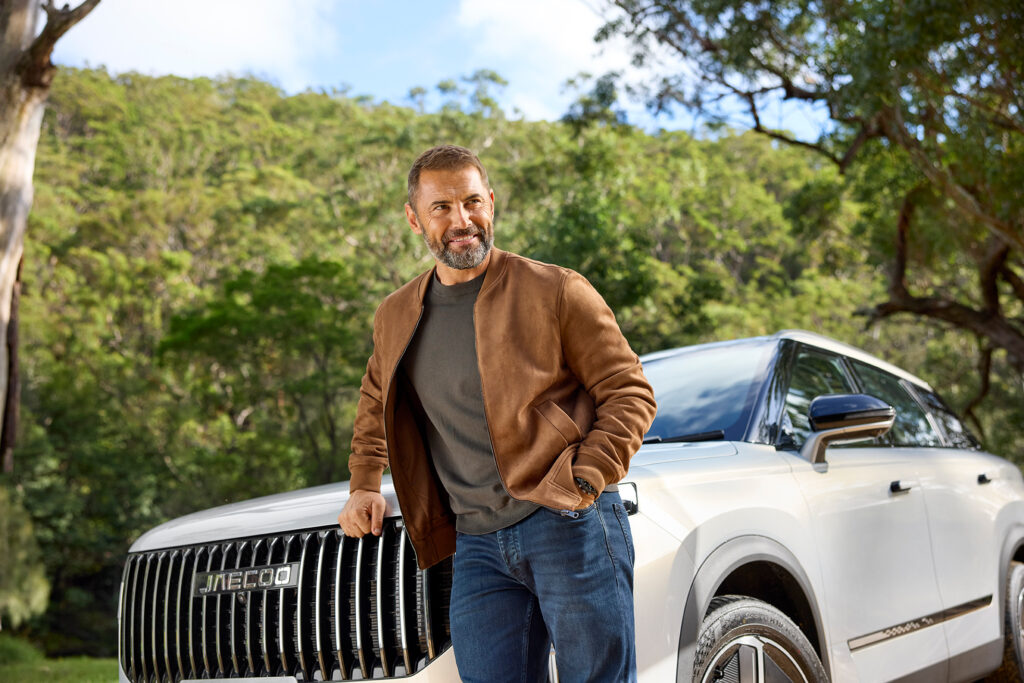

Sam Burgess

The former NRL enforcer showed toughness and lachrymosity can coexist when he lost it after South Sydney’s grand-final win in 2014.

Steve Smith

In 2018, Australia’s cricket captain broke down while apologising for the “Sandpaper-gate” ball-tampering scandal.

Don Lemon

The stoic anchor was moved to tears on live television while watching images of a police officer’s heroic actions during the January 6 Capitol riot.

Joe Biden

The US president is in touch with his emotions and is a frequent crier, whether he’s remembering the son he lost to brain cancer or thanking his loyal supporters in Delaware.

Michael Jordan

So prolific a crier that he has his own tear-streamed meme face. We’ve seen MJ cry with joy at winning an NBA title, with pride at the dedication of his own health clinic, and with pathos when speaking at the memorial for Kobe Bryant.