You commit a social faux pas. Your cheeks turn red and hot, revealing to the world your shame and embarrassment. But why? What causes us to blush and why is it a problem for some people and not others? Find out why blushing can betray your innermost fears and anxieties, but also, perhaps, reveal your strengths.

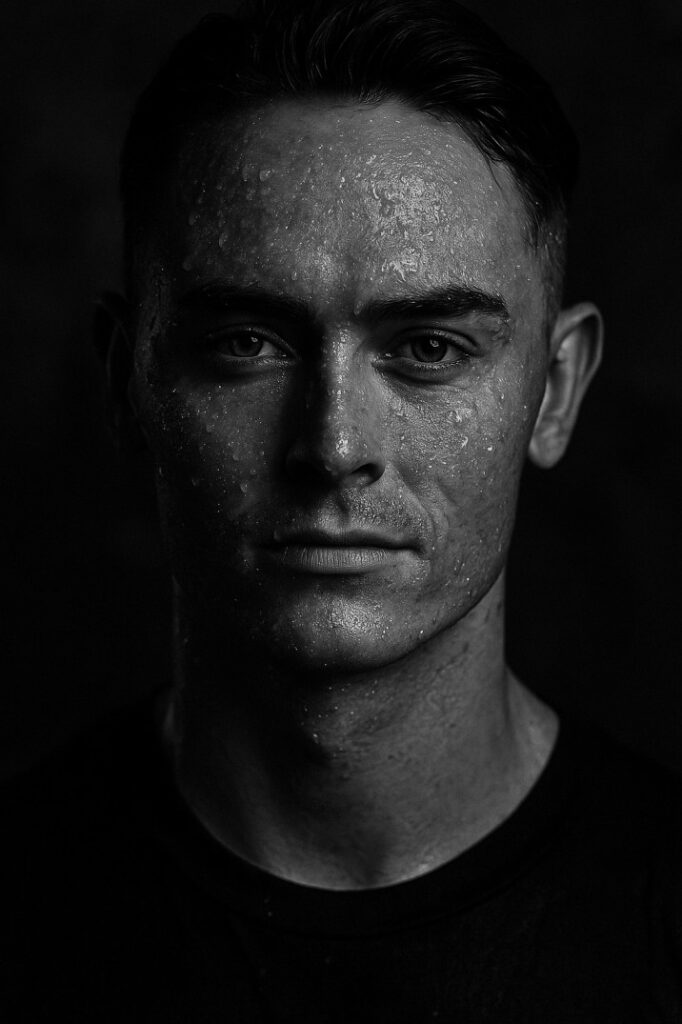

Anthony Quin doesn’t initially strike you as a shy person. The 40-year-old Englishman, who lives in Vancouver, is voluble, articulate and quick-witted. You can sense a larrikin spirit resides within him. Those qualities, combined with a strong voice, could easily have made him a natural raconteur, the life of any party.

But that’s not the Anthony Quin the world has got to see for most of his life.

Instead, Quin, a pale-skinned, real estate project manager, is a man whose cheeks light up whenever attention is suddenly focused upon him. Someone who’s tempered his congeniality for fear his crimson blotches might unmask him.

“I can blush at the drop of a hat, just from someone looking at me the wrong way, when I’m not ready for it,” says Quin, who’s talking to me via Zoom from his home office. “The ironic thing is I love being the centre of attention, but I think because I’ve had this from an early age, I’ve lived my life in quite a protected way, always trying to avoid situations where there is the potential to blush. I haven’t been able to be the person I feel that is inside of me, this very happy-go-lucky person. There’s a little bit of a joker in there, but you train yourself to be wary of things because of the blushing and the humiliation you’ve suffered.”

The problem for Quin and many people who suffer from Ideocratic Craniofacial Erythema, or chronic blushing, is that the more you focus on the condition, the worse it gets.

“If you’re in a situation where you’ve blushed people are just looking at you,” Quin says.“It can just be the most disabling, paralysing thing. Because you’re conscious of it, you’re going redder and redder, you’re feeling hot, you’re sweating. You just want the floor to swallow you up.”

Quin, whose mother was a blusher, remembers becoming aware his cheeks had the power to betray him when in the spotlight from around five years old. From then on it became a feature of his childhood and began to define him as a person. At nine he remembers having to get up in front of his schoolmates to collect a Valentine’s Day card. With his face flushed red, he endured a long, torturous trek from where he was sitting to the front of the school hall, feeling acutely aware of his glowing cheeks. Other times, kids would crowd around him, pretending to warm their hands on the heat of his crimson visage.

But such overt “mick-taking”, as Quin calls it, is perhaps less wounding than the innocent acknowledgement blushers regularly receive in adulthood. “One of the worst things is just when people, say, ‘Oh, God, you’re looking red’, which makes you go even redder,” he says.

For Quin, a comment like that could wreck an evening. Certainly, it made his adolescence and early adulthood a particularly challenging time. “Because you become very inward looking about the condition, you have this negative perspective of what you look like and how you’re perceived by other people.”

He recalls becoming obsessed with finding “a magic cure”. He visited an expensive facial consultant in London and remembers being crushed when the physician told him there was nothing he could do for him. “Man, that took me a long while to get over,” he sighs. “I was really hoping he would say something like, ‘Here you go. Take this course of drugs and off you go’.”

As a male, Quin believes there’s a natural tendency to want to fix your weaknesses and conceal the chinks in your armour. “Blushing is a sign of weakness, that’s how I definitely saw it,” he says. “It’s like, ‘How do I get rid of it? Who do I pay? I want to look perfect’.”

Quin tried everything from creams to lasers to Beta Blockers and even considered endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy surgery. But as he was to discover, there is no quick fix. That’s because blushing isn’t actually a medical condition. It’s a normal physiological response to stimuli. All humans blush, it’s just more noticeable in some people. Crucially, the way you perceive your blushing largely determines if it becomes problematic. “People everywhere show the same type of physiological reaction,” says Dr Peter Drummond, a professor of psychology at Murdoch University, who has studied blushing for nearly 40 years. “But some people regard blushing as a problem, that it’s somehow disclosing that they’re feeling vulnerable or threatened when they don’t want that to be disclosed. So, it’s sort of like a trick being played by the body upon you.”

No less than Hamlet had some wisdom that can be applied here: “There is nothing either good or bad. Thinking makes it so”.

There’s just one problem. In a society – not quite as rotten as the State of Denmark but close – in which image is prized, confidence treated as currency, judgment dispensed like confetti and shame weaponised, the ability to disregard one’s blushes is a trick in itself.

THERE WILL BE BLOOD… IN YOUR FACE

Charles Darwin was fascinated by blushing and made it the subject of the concluding chapter of his book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. In it he wrote, “Blushing is the most peculiar and the most human of all expressions”.

To appreciate just how peculiar and how human, consider that it’s one of the body’s few involuntary physiological responses that can convey authentic emotion. An actor can use their face to portray anger, happiness or sorrow. They can fake tears, definitely orgasms. But blushing on demand is tough, even for the Day-Lewises or De Niros of this world. “You can have actors playing all kinds of emotions, but you cannot play a blush,” says Dr Corine Dijk, an associate professor in clinical psychology at the University of Amsterdam and one of the world’s leading researchers on the subject. “This is something like your heartbeat. It’s not something you can control. Also, it’s not the sort of thing you can prevent while it’s happening. It’s just happening, so it’s this involuntary, tremendously visible signal.”

Before we look at reasons why you blush, you must first consider what happens when you blush. While the mechanism is not completely understood, Drummond believes blushing is a sympathetic nervous system response to a perceived threat, similar to the response the body engages when preparing for exercise. Instead of blood being shuttled to your muscles, though, when you blush it pools in the densely populated vessels of your face in an almost instantaneous response designed to release heat. At the same time, adrenaline and noradrenaline are released into your bloodstream. “It turns out that the blood vessels in the face have receptors for adrenaline and that part of the blushing response is an action of adrenaline on those receptors,” says Drummond. This then initiates a third dilating mechanism, he adds, which is an inflammatory reaction in your skin.

As you can see, how we blush, while complex, is relatively prosaic. The why, though, is fascinating. Because once you overlay a largely utilitarian bodily function with the intricacies and nuance inherent in social interaction, you create a psychological dimension that reveals a lot about who you are, what you think about yourself and how you regard yourself in respect to others.

The primary evolutionary theory for why we blush is appeasement, says Drummond. We blush to signal to others that we are not a threat to them. This can happen when we feel that we have transgressed in some way. “The trigger for blushing is some sort of worry that you’ve overstepped the mark and that people are either explicitly or implicitly criticising you,” says Drummond. “We’re trying to implicitly apologise to decrease the chances of being attacked.”

“It can just be the most disabling, paralysing thing. Because you’re conscious of it, you’re going redder and redder, you’re feeling hot, you’re sweating. You just want the floor to swallow you up”

This appeasement response can be activated not only in traditionally threatening scenarios, such as being singled out in a crowd, but also in benign social situations, such as when someone compliments you. “It might be that someone points out something favourable about you but nevertheless, it still makes you feel uncomfortable,” says Drummond. “And so you blush to try to say, ‘No, that’s not really true. I don’t want to be the centre of attention’. It’s sending that cue that ‘I’m not the threat’, to avoid any provocation.”

Social context is crucial. You will very rarely blush when alone, though you may if you were to recall an embarrassing situation. Similarly, in a study Drummond conducted in which subjects were made to sing while being observed by onlookers through a window, only the side of the face that was being observed turned red. Dijk, meanwhile, has found in experiments in which subjects’ faces were covered with electrodes, that the temperature of their cheeks rises the moment another person enters the room, even before the official experiment begins. “Your face changes colour all the time and it’s probably a very subtle social signal that we are aware that other people are present and we might have to engage,” she says.

For a full-scale blushing response to occur, though, there usually needs to be some kind of perceived social infraction, based upon an established framework or hierarchy. As Dijk points out, while most of us would blush if we broke wind in front of a colleague, particularly a superior, we probably wouldn’t if the audience was a child.

If you’re insecure in your behaviour, Dijk explains, you’re likely to become self-conscious, which makes you liable to blush, because you’re thinking about what others might think of you. “You have this remote camera perspective on yourself,” she says. “You can really feel yourself through the eyes of others and I think we have this because we are very social animals. You’re signalling to another person that you might be concerned about the impression you make and also that their impression of you is important to you.”

This shows that you know your place within the group and that you respect the hierarchy. “It’s a bit of a submissive signal,” says Dijk, who speculates that this is perhaps why blushing is often viewed negatively. “We don’t have a culture where submissiveness is appreciated anymore.” It’s possibly for this reason that historically women in literature and the arts have been positively associated with blushing – see Jane Austen’s heroines, George Costanza’s preference for women with a “pinkish hue”. But in a more egalitarian society or in an environment as socially combative as some workplaces can be, to unwittingly communicate submissiveness may not be in your best interests.

All of this is very normal behaviour, even if it appears strangely anthropological when you take the time to examine it. The problem for some people is that from childhood onwards they begin to focus unduly on their blushing. They come to anticipate it and fear it and that only makes it worse.

“Blushing itself isn’t a physiological problem,” says Drummond. “But the fear of blushing can be a psychological problem.”

BLOODY HELL

Like Quin, I’ve always been prone to turning tomato when I find myself the centre of attention. Naturally shy, over the years I have definitely regarded the spotlight as a threatening situation, eyeballs converging on me like hollow-pointed bullets. But until now I’ve never really thought to examine why I’m so uncomfortable. Upon reflection, if I were really to try to identify the roots of my discomfort, I believe it can be traced back to the onset of puberty and my corresponding interest in girls.

Prior to my teenage years I didn’t really care too much what the opposite sex thought of me. Now, as I look back, though, I realise that from around 13 onwards I cared a great deal. Probably too much, causing me to shrink from the spotlight in situations in which I felt people, particularly girls, might be evaluating me. Where in primary school, for example, I would regularly and enthusiastically raise my hand and volunteer an answer in class discussions, in high school I began to keep my hand down and my mouth resolutely shut. Of course, teachers have an uncanny knack for identifying those who don’t wish to participate (or so it seemed to me). Then 20 sets of eyeballs, some 10 of them horrifyingly female, would be on me, as my cheeks reddened, my heart began to pound, my breath quickened and my wretched voice abandoned me. In hindsight, this confluence of reactions probably cruelled my ability to think straight. At best, I would offer a paltry “I don’t know” to the teacher’s inquiry. Eventually they would move on, and mercifully, the spotlight with them. Afterwards, I would feel ashamed of my pathetic performance and, of course, dread the next time a teacher might call on me.

These days the spotlight is not quite as socially crippling for me as it once was as an angst-ridden teenager. I’ve grown more confident in myself and in my place in the world. I’m a married man, so (in theory, at least) am less concerned about the impression I make on females. Ultimately, I care (slightly) less about what people think of me. And while it could be interpreted as aloofness or even arrogance, when it comes to blushing, not caring quite so much about others’ opinions of you might not be such a bad thing.

Whether or not you become fixated on your blushing and come to fear it, as Quin did, or are able to shrug it off, hinges on your levels of social anxiety. “One of the most remarkable things I’ve found is that when you force people to do silly things, there’s not much difference between the intensity in the blush in people who are afraid of it and those who aren’t,” says Dijk. “But in the self-reporting there’s a massive difference. People that aren’t fearful of blushing underestimate the intensity of their blush because they just didn’t pay attention. People who are afraid of it say, ‘I blushed tremendously’. What you notice in shy people is that the concern about blushing becomes a concern in itself.”

Blushing for socially anxious people can become a very vicious circle, confirms Drummond. “It may be that people are generally socially anxious and they then become aware that they’re disclosing their anxiety and other people know that they’re feeling anxious because of their blushing and so they then become frightened, not of blushing itself, but frightened of thinking that they’re blushing.”

How to escape such a maddening spiral? The first step is probably the hardest: accept there’s nothing you can do about it. It’s normal. The second step is something that may seem equally incomprehensible to serial blushers but is true nonetheless: acknowledge that there are positive aspects to blushing. Because as problematic and socially debilitating as his rosy cheeks have at times been for Quin, they have also proved an unlikely asset, particularly in his job overseeing large-scale real estate projects. “I think what blushing does do is keep you quite honest,” he says. “I’m terrible at lying and if I ever got caught doing something my face would definitely tell it all.” Quin’s red-hued transparency has proved invaluable in a profession where deceit or opaqueness could have huge ramifications. “Especially in the job that I do, if I say, ‘I’ve done something wrong’ or ‘This has gone wrong’, people really appreciate that. And it’s like, ‘This guy, there’s no bullshit there’.”

“If you’re less anxious then you’re less likely to blush and be less concerned if you do blush”

By unconsciously acknowledging social conventions, blushing could also make people more likely to look favourably upon you or forgive you for social missteps, says Dijk. If in a situation where you spilled coffee over a colleague’s trousers, for example, blushing tells the person that you acknowledge what you did and are sincerely sorry about it. “It’s not that they trust you more as a person, but they trust the value of the apology more,” she says. If you weren’t to blush or even mildly colour in such a situation, however, it’s possible people would regard you suspiciously or conclude that you’re clumsy and liable to do it again or even regard you as a sociopath. Without blushing your words may not be freighted with authenticity. “Because you also have this involuntary signal that cannot be faked, it adds to your embarrassment signal,” she says. Blush it ’till you crush it, perhaps?

Conversely though, research by Dijk’s colleague, Dr Peter de Jong, has found that if people are not sure why you blush, it can appear as an admission of guilt. Say you’re on a train and the conductor asks for your ticket. You frantically look in your bag but cannot immediately find it. “If it’s ambiguous if you did something wrong, and you start to blush, people will think you are guilty,” warns Dijk.

Which, of course, for the serial blusher, is another thing to worry about.

SPARE YOUR BLUSHES

As a blusher, I find the idea that the condition may have some positives to be heartening. Yet as tempting as it may be to focus on those, or even reframe blushing as your ‘superpower’ or intrinsic authenticity signal, if you are someone who regards it as a problem, you must go further still. You must strip blushing of its power altogether.

For Quin, the demands of his job have meant he’s simply had no choice but to plough on in the face of his, ahem, red face. “I think in a way my job really helps me because I have to be a person that’s leading others and I have to just ignore the thought of blushing even entering my mind,” he says.

Reaching out to other sufferers on social media has been hugely beneficial, he adds, helping him realise he isn’t alone in his scarlet-faced misery. He also feels that being a chronic blusher makes you more empathetic towards others, understanding that “everyone has baggage to deal with”.

But while becoming more attuned to other’s feelings through the crucible of your own suffering is certainly commendable, says Drummond, the real key is to become less concerned with their judgments.

“I think the problem really is that people read too much into what they think other people are thinking,” he says. “Most of the time people will say, ‘Oh no, I didn’t even notice you were blushing’. So, largely, fear of blushing is in the mind of the blusher. And it’s a fear of what might happen rather than what is happening.”

For that reason, if you regard blushing as a problem, you’re best to focus on treating your social anxiety rather than on tackling blushing itself. “That way, even if you feel yourself blushing it’s no longer a fear for you,” Drummond says. In this way, he adds, you have a chance at reversing the spiral. “If you’re less anxious, then you’re less likely to blush and you’re less likely to be concerned if you do blush. Which will also mean you’re less likely to blush.”

I try to remember the last time I really blushed. I know it’s happened at some point over the last year or so, but I’m struggling to pinpoint the exact occasion. And then it dawns on me. The fact I can’t remember represents something of a victory. One, though, that in the circular nature of this thing, if I were to actually share it with someone, would probably cause me to blush. I even feel my cheeks starting to heat up at the prospect. Then I have another thought. Who cares?

HANDLE YOUR HUE

1. Breathe

In a situation where you feel uncomfortable with attention, take a few deep breaths to help your body relax. This will help halt the release of stress hormones and return your heartbeat to normal.

2. Treat underlying anxiety

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can be an effective treatment for many anxiety-related conditions. CBT works by challenging negative and unrealistic thoughts that cause unhelpful feelings, bodily responses and behaviours.

3. Stop focusing on yourself

“Learn to control where your attention goes,” advises Dijk. “What is the other person saying? What’s happening? Socially anxious people tend to focus only on themselves and lose track of signals the other person is displaying.”

4. Put it in perspective

Blushing is just one signal in your body’s physical response to stimuli. “I think blushing is healthy but if you’re bothered by it, then you’re likely Overestimating it,” says Dijk. “It isn’t that important in forming other people’s opinions about you. They might think you’re a bit shy, but still think you’re very competent. It’s just this one signal that shows you care.”