Before you can understand Nazeem Hussain, you must first appreciate the force of nature that is his mother. A single mum who brought up three kids at a time when divorce was frowned upon in Melbourne’s Sri Lankan community, Mumtaz Hamid worked around the clock as a bookkeeper, a kitchen hand and a leaflet deliverer, among other things, to make sure her kids grew up with opportunities to do whatever they wanted, even if that included walking away from a secure career in tax law to become a stand-up comedian. Something she never did, though? Back down from a fight.

“My mum, if you try to put her in her place, she’ll put you in your place,” says Hussain, who’s talking to me from the kitchen of his home in St Kilda East, as he finishes a bowl of yoghurt, banana, Weetbix and protein powder. “She’s a very strong woman.”

Whose mum isn’t you might ask? Well, not every mother, upon being brushed off by the school principal after complaining about the racist bullying of her eldest daughter, marches into the local MP’s office to escalate things. The local MP? That would be Jeff Kennett, Premier of Victoria. “She walked in and the receptionist was like, ‘Can I help you?’” Hussain recalls. “My mum said, ‘I want to speak to Jeff’. The receptionist was like, ‘Who are you?’ So, my mum walked straight past the receptionist into Jeff Kennett’s office. I don’t know what she said but 45 minutes later, she walked back into the principal’s office with Jeff Kennett. Jeff Kennett looked at the principal and said, ‘Just please do whatever this woman wants you to do’. And from that moment on the bullying stopped. She has that take-no-bullshit attitude.”

It’s one of many stories Hussain tells me about his mother. Another time, Hussain wondered why, after moving to a new school and being bullied himself, the taunts suddenly stopped. Then he saw his mum at the bus stop, handing out bags of lollies to the bullies in the year above. “She had literally bribed one group of bullies to keep another group of bullies off my back,” he laughs. “She’s a gangster. I think maybe I received that wiring from her.”

He would need it. Young Hussain instinctively responded to racially tinged schoolyard insults with his own rapid-fire volleys of creative invective. “I think I naturally responded to taunts or to being excluded assertively,” says Hussain.

“If you took a shot at me, you better be ready for a shot right back. And so, when people couldn’t handle my mouth, they would often try to fight me and I’d run. I was a fast runner. I do remember being decked once or twice. But then, I’d end up humiliating the guys that did it to me and everyone would be laughing at them. I guess I developed my sense of humour in those years.”

He didn’t know it at the time, but by using humour, not only as a shield but as a weapon, he was building something every good comedian needs: fearlessness. It would make him his mother’s son. And like her, in the Australian entertainment industry at least, something close to an unstoppable force.

DIFFERENT STROKES

For any immigrant or minority, it’s never the taunts or teasing that get you. It’s the stuff that’s unsaid. The stuff that makes your skin hot and your stomach turn. The silent shame of being different.

“Sometimes racism is just reduced to name calling and I got that throughout my whole childhood,” says Hussain. “‘You’ve got shit on your face’. ‘Your mum talks funny’. ‘Your food’s weird’. But it’s only the one per cent that verbalise those thoughts. It’s all the exclusion and the silent stuff that you see and observe and experience that forms the majority of the racism you encounter.”

As one of the few coloured kids at a school that was largely white, Hussain knew he was different from very early on. The natural response as a kid, he says, is to want to fit in. And when you don’t, you feel embarrassment and self-loathing about who you are. “I remember just not liking my own skin colour, feeling embarrassed when my mum would come pick me up or when my friends would hear her talking.”

Hussain and his sisters became adept at flipping between cultures. Being Sri Lankan at home and “as Aussie as we could” at school. There he might slide into a more nasal register and employ a vernacular weighted with irony – strangers are ‘mates’, friends affectionately addressed as ‘bastards’ or ‘pricks’. “That’s the thing with being from another culture, you become experts at your own culture, but you also completely understand white culture,” says Hussain. “Straddling both worlds and trying to keep them apart was something that was a central feature of my childhood.”

It wasn’t until he was older and started to hang out with more non-white kids that Hussain began to realise that his experience wasn’t unique. In his late teens, exploring what it feels like to be different and sharing that perspective with others who knew it too, would lead him into comedy. Because often the best way to respond to the shame of being an outsider and the wounds of exclusion, is to find people with whom you can share that pain and laugh about it together.

Heal through humour

The early 2000s weren’t a great time to be a Muslim in Australia. After 9/11 and later the Cronulla riots, a community that had previously gone under the radar in terms of racial vilification, suddenly found the spotlight upon them.

“I lost friends because people changed their views on Muslims,” says Hussain. “We were suddenly made to feel like a threat to the Australian way of life, which we had been a part of since birth. People were having their hijabs ripped off, my sisters were wearing the hijab at the time.” Sharing a surname (albeit one spelled differently) with you know who, didn’t help.

If you took a shot at me, you better be ready for a shot right back

Hussain had begun hosting trivia nights at Muslim community events and remembers feeling great joy in making his community laugh. “Sometimes the worst situations are the funniest,” he says. “Especially when there’s so much hysteria. A laugh is an emotional reaction to something. You laugh in solidarity, you laugh as a release, as a stress relief, like, ‘Yeah, that is absurd. That is fucked up’.”

Some of Hussain’s humour directly recalled the racism and bullying he’d experienced as a kid. “Especially when you can make a joke about the racist, it’s almost like making a joke about the bully,” he says. “You’ve got a microphone this time.” He compares the energy in the room to being at a rally. “Especially when you’re in a room of just Muslims or just Brown people, everybody there is on side with each other. And there’s something really nice about feeling that energy around you. You realise you’re not this crazy person that’s experiencing this alone. Doing that was very addictive for me.”

After finishing school and studying law and science at Deakin University, Hussain began working as a tax consultant at Price Waterhouse Coopers, while pursuing comedy on the side. He appeared on the Channel 31 show Salam Cafe with friend and later colleague on The Project, Waleed Aly (the two prominent Muslim entertainers are frequently, and perhaps predictably, mixed up in media reports). Around the same time, Hussain and his friend, Aamer Rahman, competed in Triple J’s Raw Comedy competition. Rahman made it to the nationals while Hussain got through to the Victorian State Final. “After that we thought, “Oh, okay, this is harder than it looks, but I think we can do it,” Hussain says. The pair formed the duo, Fear of a Brown Planet, putting on a show at the Melbourne Fringe Festival that sold out, before taking it on tour.

His side hustle was going places, but Hussain says he never actively thought about leaving his job at PWC until SBS greenlit a TV idea he’d pitched to them. “I was like, ‘Ah, shit.

Now I’ve got to film it’.” He went to his managers and apologetically asked for time off. “I always downplayed my comedy and they said, ‘No, Nazeem, are you insane? The corporate world is always going to be here. This is what you enjoy doing. Just go do it’.”

The show was called Legally Brown. He took six months leave without pay to make it. It would be recommissioned for a second series and later nominated for a Logie. Things started to roll. He never went back.

I’m still here today because I’ve tried to say what I think in front of any audience

PLAYING THE RACE CARD

A couple of years ago I interviewed Hussain about his first gig as a rising comedian in front of a largely white audience in a country town. It was a big step for him at the time, highlighting one of the central features of his act: identity. As soon as Hussain tells a joke to an audience from outside his community his humour takes on a different dimension. Sometimes it’s branded as political or identity-driven, edgy or progressive. Hussain is used to these labels, although they’re never ones he’s actively pursued. His only goal, he says, is to make you laugh.

“If you’re funny, you’re funny. People know what funny is. I think if someone’s like, ‘Go to that guy’s show, he’s very interesting and clever and edgy’, I don’t know if that’s what I want people to say about me. I want people to leave my show and go, ‘That was very funny’.”

In his early years Hussain’s challenge was to maintain the fearlessness and irreverence of his act while performing in front of audiences who didn’t directly relate to it. “My natural reaction was to just go, ‘Ah, there’s white people here’ and just not say the things that I think,” he says. “You put on a different face, you put on a white voice and you try to appear less threatening. But I guess I’m still here today as a comedian because I’ve tried to say what I think at all times, in front of any audience.”

Speaking of labels, one that gets tossed around a bit in Hussain’s shows is one many of the audience aren’t always ready for: ‘White people’.

“In Australia, you can go, “Oh, he’s Indian, he’s Brown. He’s this, he’s that’. But as soon as you point out a white person’s ethnicity, they’re like, “What are you calling me? I’m an ethnic group? No, I’m normal’. Whereas I think in America or the UK, they’re a little beyond that.”

Hussain’s identity, together with his pull-no-punches style, has made him a target for online vitriol. He can’t help focusing on abusive tweets and DMs and often fights an internal battle over whether to respond in kind (that mother wiring) or to try to engage constructively with people who’ve just abused him.

“I actively have to tell myself to stop and calm down and then sometimes if I do respond, I will respond in a kind way,” he says. “And that doesn’t feel nice at the time, but I know it’s the better thing to do.” Many times, he’s offered to meet up with his abusers in real life – one bloke even took him up on his offer and the two met for a chat at Flinders St station.

Invariably, directly acknowledging abusers either mutes their anger or disarms them completely, he says. “It always ends nicely. I think just acknowledging someone’s pain, saying, ‘Hey, I’m really sorry you feel that way’, unsettles them because I don’t think they think you’re going to reply. And as soon as you do, they’re like, ‘What the hell? This is a person?’ They almost immediately come back with, ‘Look, I’m sorry, mate. I was just feeling upset’. You immediately get a U-turn.”

Hussain has felt the challenges of navigating the viper pit of social media more keenly recently. Earlier this year his father died from COVID-19 in Sri Lanka and he admits to feeling triggered by anti-vaxxer and anti-lockdown sentiment he comes across online. “The news is feeling much more personal than it’s ever felt for me before,” he says. “The more I think about how my dad passed – he was double-vaxxed but he was a donor recipient – he did all the right things. He got COVID because it spread, in some part, because people were flouting rules and transmitting it. So, it’s almost like, well, but for those actions, would my dad have caught COVID? Who knows? Those questions come to mind a lot.”

LIVE AND LAUGH

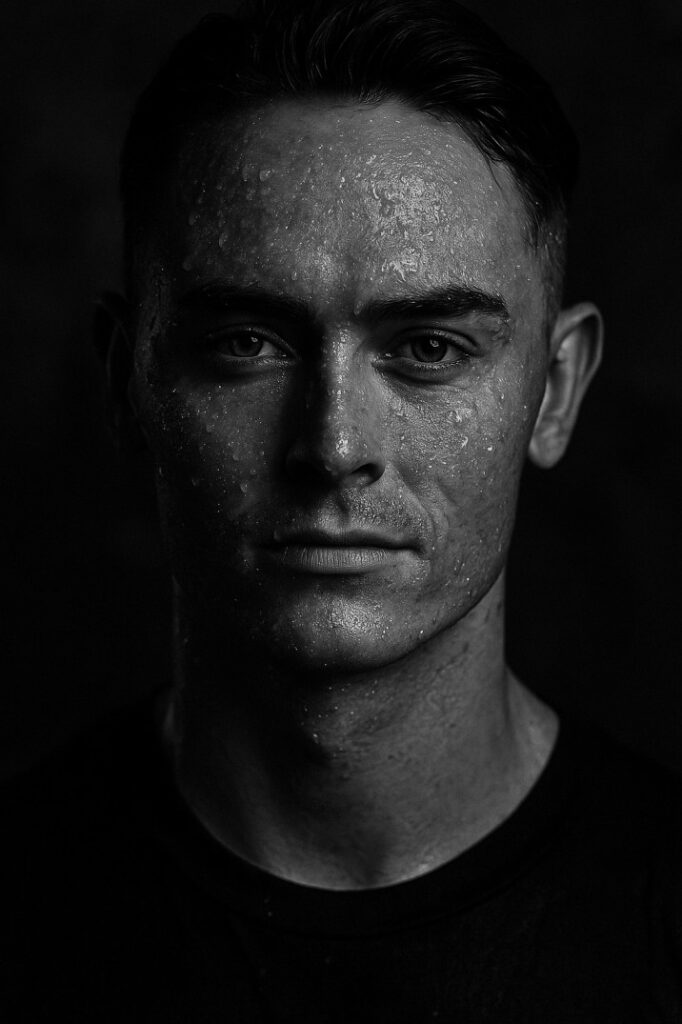

At 5.30am on the morning we speak, Hussain found himself working out underneath a bridge near a skatepark with a personal trainer. If you’d told the 36-year-old he’d be doing that a few years ago, he’d have laughed at you, maybe even made a ‘bit’ out of it to take on stage. The fit comedian is in many ways as oxymoronic as the skinny chef (the mentally unscarred comic, meanwhile, is perhaps an even more ludicrous proposition).

All jokes aside, in 2019 Hussain went from looking at his body and thinking he should lose weight to actually doing something about it. “Then you see your hard work paying off,” he says. “It does make you feel good. It’s one of those things that you can control when everything else is falling down.”

So, what was the trigger for him to start taking his health more seriously? “Separation,” he says with a chuckle, before providing a quick summary of the last few years: “Dad, divorced, remarried.”

Hussain has a three-and-a-half-year-old son, Eesa, who he jointly raises with his ex-wife. After his own father left the family and returned to Sri Lanka when Hussain was six, he’s conscious of how much his presence can help shape his son’s life. “I think I’m parenting via what I know I missed out on,” he says. “I missed lots of contact time. I’m extremely tactile with my kid and it’s the best part of my life, being a dad.”

Our conversation turns to his future plans. With COVID putting the live entertainment scene on hold over the last 18 months, Hussain is looking forward to getting back on the road and touring his stand-up next year. He’d love to film one of these shows for a one-hour stand-up special so beloved of streaming services, having already done a half-hour show, Public Frenemy, on Netflix in 2019. And right now, he’s working on a narrative comedy that he hopes will be produced next year.

But stand-up remains his focus and as we chat about his comic heroes – Eddie Murphy, Dave Chappelle, Margaret Cho, Hughsey, Julia Morris – he concludes that it’s something you have to keep doing or risk losing your edge. Thankfully, he says, it’s a skill you can get better at with age. Why? Because of all the cuts and bruises you sustain along the way.

“I think with comedy, the more broken you are, the more life you have behind you, the better you are as a comedian,” he says. “You’ve got more to say.”

Given how much Hussain’s experienced and endured already, you can only wonder how funny he might be in a few years’ time.