My therapist approaches my tales of dating apps and booty calls and ghostings with an adorable anthropological fascination. Recently he asked me whether a man I was dating paid for my meals and drinks. “Of course,” I replied. “Hmm,” my therapist said. His “hmm” is the verbal equivalent of looking skeptically at someone over your spectacles, and I knew where he was going: doesn’t a man paying for a date add a transactional tension to what follows the date? And if gender equality is the goal – isn’t that always the goal now? – shouldn’t men and women split the bill evenly?

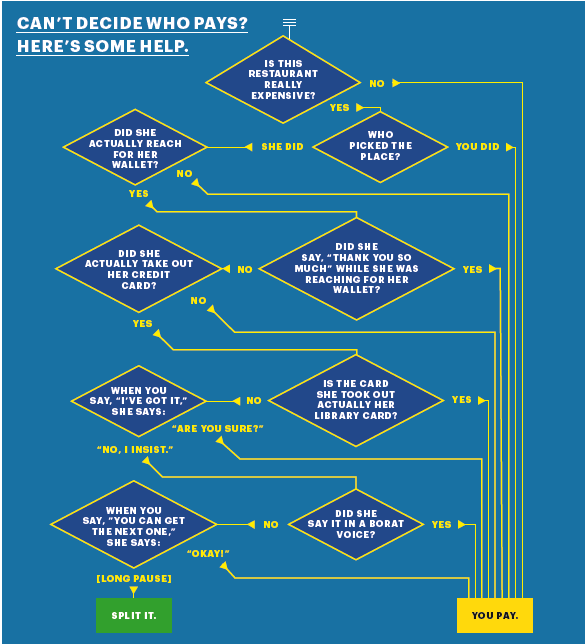

Well, no. For most of my dating career, I’d feint for my wallet when the cheque arrived, and if my date didn’t immediately say, “I’ve got this”, I’d exaggeratedly grope around the depths of my purse to give him more time to do the right thing. Sometimes I even halfheartedly offered to split the bill, but I never insisted, and men rarely accepted. If they did let me split the bill, it wasn’t a deal-breaker, but it was a ding: “It was a great date,” I’d tell my friends. “But he didn’t pay.”

A month later, I was at a fancy restaurant with a date, and I was spiralling. I’d never really questioned whether men should pay on first dates. We had been nursing Negronis at the bar for hours. On either side of us, two rounds of first dates had arrived, run out of things to talk about, and left, but we were still going strong. He asked the bartender for the bill, put his credit card on the bar and scampered off to the men’s room. While I was alone, the bill came, and I stared at it like it was the Black Spot. I was paralysed by etiquette: it seemed presumptuous to hand my date’s card to the bartender, but even more presumptuous to wait for my date to return so that I could make a show of reaching for my wallet.

RELATED: Here’s The No.1 Thing You Can Do To Land A Second Date

I realise that by offering to split the bill when I in fact have no intention of doing so, I’m putting my dates in a difficult position. Chivalry tells us that men must pay on dates, but here I am, pressing to pay my part. It’s like that movie trope in which one character tells another: “Whatever happens – no matter how much I plead, no matter how much I scream – do not untie me”. Invariably the other character caves to his buddy’s pleas, unties him, and everyone dies. When you’ve been told never to let a woman pay for dinner, how do you know when to take her up on her offer?

As I stared at the bill, my therapist’s “hmm” echoed in my head. So did the phrase “benevolent sexism”, which I’d learned recently and had been overusing ever since. “Benevolent sexism” was coined by professors Susan T. Fiske and Peter Glick in a 1996 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Its counterpart, “hostile sexism,” is rooted in a belief that women are intent on seizing male power, possibly through blowjobs and feminist guilt trips. Though the same man can demonstrate both hostile sexism and benevolent sexism, depending on the situation, research has shown that generally men have a favourable opinion of women. So, Fiske and Glick write, “how can a group be almost universally disadvantaged, and yet loved?” The answer lies in the phenomenon of benevolent sexism, or a man’s belief that women require men’s protection and support.

RELATED: Here’s The Right Way To Ask Someone Out On A Date

More free dinners for me! But, Fiske and Glick write, benevolent sexism has a downside: “If men’s power is popularly viewed as a burden gallantly assumed . . . then their privileged role seems justified”. In other words, when we all accept that it’s a man’s job to shepherd a woman through life, then why not make him her boss, too? Why not pay him more? Fiske and Glick go on. “Women who seek power may consequently be perceived as ungrateful shrews or harpies, deserving of harsh treatment.” Women can be complicit in benevolent sexism: when I let a man pay for my dinner, Fiske and Glick suggest, I’m bolstering the image of myself as a dependent.

So yes, in theory, a man paying for my dinner is sexist, and I’m reinforcing the patriarchy a teensy bit by accepting that free dinner. But in practice, I don’t think anyone is considering the gesture in those terms. I think we’re all too stressed about not doing weird nasal laughs or slurping soup on our dates.

When I asked a few women whether they allow men to pay on dates, they all said yes – and then they all qualified that yes. One said she thinks of a man’s paying for dinner as a sort of “man tax”: if men are going to get paid more than we are, and have privileges that we don’t have, and not have to give birth and stuff, then they should pay for dinner. Another woman said that she’ll let a man pay for a few dates, but then she’ll cook him a really nice dinner – balancing out one old-timey, gendered gesture with another. Another said she’ll let a man pay for dinner on a date only if she really likes him. If she’s not planning to see a guy again, she throws her card down.

A man’s paying for dinner is a gesture that’s withstood the test of time simply because it helps us breeze through an awkward moment after dinner. The reason scripts like “he pays” have persisted is that they make things easy, and that’s what makes them so insidious. Sticking with them is easier than negotiating a new social contract.

RELATED: The Best Way To Approach A Woman At The Bar

Before that can happen, we need to lay the groundwork. First, we find that we have to work a little harder to justify upholding the old rule (my friend’s “man tax”). Then we begin to outline situations in which it doesn’t apply, like the woman who insists on splitting the bill when she doesn’t want to see a man again. Then we start calling each other out for following the rule, like my therapist called me out. Finally, we all break the rule.

We’re not quite there yet. At that fancy restaurant, while my date was in the bathroom, I snuck a peek at the total on the bill and Venmo’d him for half before he returned to our table. He never mentioned it, and I still feel like I committed a faux pas. Maybe he’s a benevolent sexist. Maybe I’m a benevolent sexist. Or maybe we were both just terrified of sending the wrong signal.