This is an excerpt. To read the full story, pick up your copy of Mr. Jones instore at David Jones.

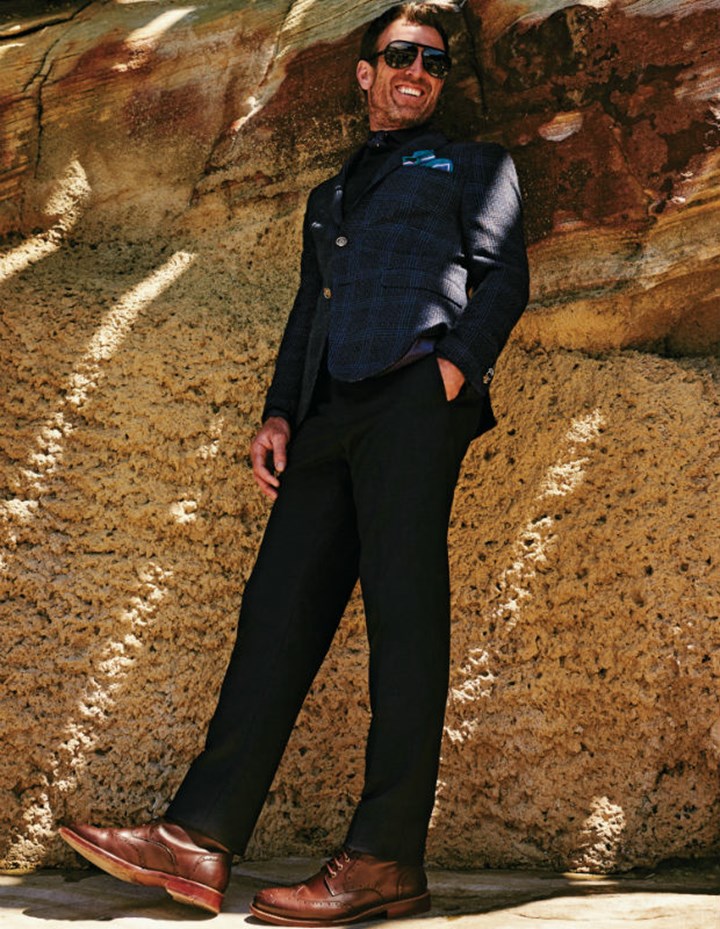

I first meet NIGEL BRENNAN at the David Jones Personal Shopping Suite in the centre of Sydney, where he is being fitted for the garments he wears on these pages. The topic of his kidnapping comes up almost immediately, with the 45-year-old breezily saying that recently, at his home in Hobart, he went on Google Earth and found the house in Northern Mogadishu where he was held captive.

Opening my computer, I ask if he thinks he can find the house again. The screen moves from Sydney across Australia, the Indian Ocean and Madagascar until we stop at the east coast of Africa. He zooms in to Somalia and, once the greens become browns, then reds, settles on the Somali capital of Mogadishu.

From the centre of the city, Nigel traces an arterial road north-east called Balcad Road, through endless low-rise city blocks towards the fringes of the city.

‘There it is, that’s the mosque,’ he says pointing at a wide, white roof; a building with a garden three structures east of the main road.

This is where Nigel and Canadian journalist Amanda Lindhout fled, after a short-lived escape attempt five months into their captivity.

After finding loose bricks at the edges of some south-facing barred windows of the house they were being held in, Nigel and Amanda had decided to escape one night. In the dark, they would try to bypass the roadblocks and gunmen of the city and make their way to the coastline and the government-controlled airport.

The plan changed and the need to escape became urgent the day their tormentors told them that the Somali fixers they’d been captured with had just been executed. Nigel and Amanda decided they must leave immediately.

Hearing the call to afternoon prayer, the pair decided to run to the mosque that must be nearby, and throw themselves on the mercy of the congregation. For pragmatic reasons, both Nigel and Amanda had converted to Islam some months earlier, and hoped those good Muslims would see them as brothers and sisters worth saving.

When Amanda and Nigel jumped from their cells, they were free for their first time in nearly 150 days. Under a hot, cloudless sky, they found themselves face to face with a Somali man who was tending to his garden.

Hearts thumped, adrenaline pumped.

‘We could see a market or something going on here,’ Nigel says, pointing to Balcad Road. ‘I thought maybe we should change the plan and run there.’

A young boy emerged and sprinted away when he saw them, likely off to alert their captors. This killed any ideas about improvisation. Nigel and Amanda ran toward the sound of prayers. Inside the mosque, Nigel shouted ‘I caawi, I caawi,’ the Somali words for ‘help me’.

Two men in their fifties were sympathetic and one told Nigel that the imam was nearby and implored them to stay where they were. ‘He will return and he will help,’ the man said, in English.

Two teenage gunmen, Nigel and Amanda’s jailers, burst into the house of worship, ready to retrieve their quarry. The older worshippers charged the gunmen and pinned them to the wall, telling them that what they were doing was haram – forbidden by Islamic law.

Nigel remained hopeful, until a second group of older, more aggressive men with AK-47 rifles ran into the mosque. Those men quickly took control of situation, terrorising the congregation into submission, and physically dragging Amanda and Nigel back to the house they had been held in. Nigel points that house out on my computer screen, also. It has a light blue roof, a yard of brown dirt and opens up to a laneway that feeds to Balcad Road.

This house, indistinctive in the sprawling East African metropolis, would be the place where Nigel and Amanda would be punished severely for the crime of trying to gain their freedom.

Nigel Brennan had come to dry, flat Mogadishu from a location that couldn’t have been more different – a craggy, green private shooting estate owned by landed gentry near Loch Lomond in Scotland. Nigel’s girlfriend was the executive chef and Nigel did odd jobs for the head gamekeeper and took official photographs for guests and hosts.

Nigel had studied photography at university, but had only taken on a few minor photography jobs afterwards. It was a passion though, and he was making a concerted effort to join the staff of a major metropolitan newspaper. At 35 years of age however, he was having little luck.

An editor at the Courier Mail had told him that, at his age, the fastest and surest way to a steady gig was to make a big impact as a freelancer. This is why an offer from his friend Amanda to travel to one of the most under-reported warzones in the world was so enticing.

Amanda Lindhout, who had just turned 27, was also striving for a steady job in the media. She had no formal training as a journalist, and little traditional experience, but had worked previously in conflict zones, with stints in both Kabul and Baghdad.

When Nigel and Amanda arrived in Mogadishu, the city was likely the most lawless and fractious place on earth. The weak transitional government was only policing Villa Somalia, the traditional centre of government in the country, and a handful of blocks around it. The African Union had a few other strongholds outside the centre of the city, but the rest of Mogadishu had largely been left to criminal gangs and Islamic extremist groups.

The biggest and most dangerous of those groups was Al-Shabaab, a brutal organisation aligned with

Al-Qaeda who were in conflict with both the transitional government and African Union.

After arriving at the Hotel Shamo (currently closed after being destroyed by a massive truck bomb set by Al-Shabaab) close to the airport, Amanda attempted to befriend Robert Draper, an American National Geographic journalist staying at the hotel. She wanted to know where the fighting was heaviest, so she and Nigel could visit. Robert Draper says he was shocked and alarmed by Amanda’s recklessness.

Robert Draper emailed his girlfriend, writing of Amanda: ‘She’s going to get herself or someone else killed.’

Amanda wanted to visit Bakara Market, a notorious hotspot in the city where a large battle between US forces and Somali militiamen (explored in the film Black Hawk Down) had taken place in 1993. Their local fixer said visiting the market would be tantamount to suicide. Eventually he agreed to take the pair to a refugee camp outside the city instead.

On the morning of 2 August 2008, Robert Draper, a French photographer named Pascal Maitre and a large local security retinue set off for the ancient port city of Merca. Nigel and Amanda followed, with their fixer, two drivers and two hired gunmen.

When their vehicle arrived at the Somali National University on the fringes of the city they found that African Union (AU) soldiers had garrisoned the compound.

The gunmen protecting Nigel and Amanda asked to get out of the car, saying that they were concerned that they would be confronted by the AU.

Draper’s bodyguards had been let though with their weapons, so this confused Nigel, but, completely misunderstanding the gravity of the situation, he and Amanda chose to go on without them.

Robert Draper thought Amanda was going to get someone killed, but actually it was he who almost did. Draper’s local head of security had sold him out to a militia planning to kidnap him, but when a spotter at the hotel saw two other westerners with a much smaller security force, they decided to move on the pair instead.

Three or four kilometres away from the university, on the road to the town of Afgooye, a group of men with AK-47 rifles swarmed Nigel and Amanda’s Land Cruiser. Amanda and Nigel were blindfolded and driven deep into the city.

A few days later Nigel’s sister Nicole received a call from Somalia at her home in Moore Park in Sydney.

‘This is a ransom,’ a man named Ali Omar Ader, but who had identified himself as ‘Adan’ said. ‘We are demanding US$2.5 million per head.’ In Alberta, Canada, Amanda Lindhout’s father received a similar call…