A comedian walks into a bar.

“What’s up?” says the barman. “You look sad.”

“Well, how would you feel?” replies the comedian. “My whole life’s a joke.”

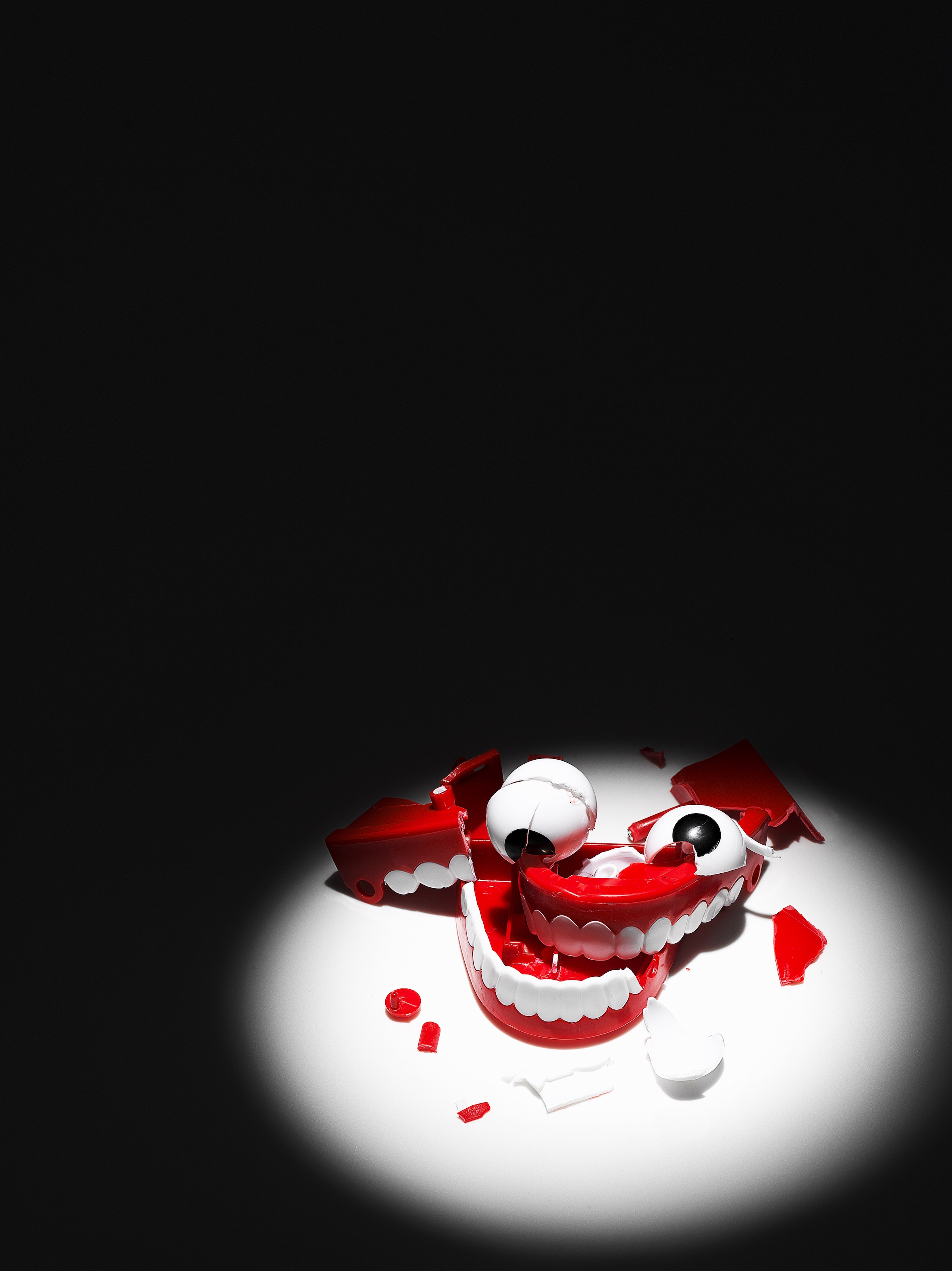

Comedy and inner turmoil have a long history. It’s a relationship that can be both symbiotic – the best humour often comes from the darkest places – and inherently hazardous. An analysis of New York Times obituaries found performers die nearly eight years younger than members of the military. Similarly, a study at the Australian Catholic University found that, on average, comedians’ lifespans were three years shorter than those of dramatic actors, at just 67 years of age.

A working environment that combines late nights, endless access to alcohol and drugs, plus long, often solitary touring further impacts on the health of individuals who are often uniquely vulnerable. A study in the British Journal of Psychiatry found comics were more likely than the general population to exhibit traits associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The researchers suggest

manic behaviour could inspire out-of-the box thinking. Others speculate that comedy could serve as a self-defence mechanism.

“What comedy does is take a normal situation and tip it upside down, which is basically what you do in cognitive behavioural therapy,” says psychologist Dr Tim Sharp. “It puts things in perspective.”

We asked three of Australia’s leading comedians, Jimeoin, Damien Power and Tom Gleeson, to reveal how they deal with the extreme highs and lows intrinsic to their profession. As men known for mining their vulnerabilities for comic gold they’re better placed than most to offer insights into how to deal with your inner demons, as well as reinforce just how important it can be to see the funny side, even in the bleakest of circumstances.

NAME: Jimeoin

HOME: Melbourne

AGE: 51

“I totally fell into stand-up. I was at a pub playing pool. In the other room there was a comedy night. A girl we were with was in it and she put my name down. Next thing this guy comes up and goes, ‘Hey, you’re on second in the next segment’. I’m like ‘Doing what?’ He goes, ‘doing stand-up’.

So I just got up and told three jokes.

I really enjoyed people laughing. I’d always wanted to be in a band or an actor, anything other than a real job. This seemed to be something between the two.

I loved the fear. I loved the adrenaline rush and that nobody knew what I was going to say. To this day, nobody knows what I’m going to say.

But it has drawbacks. It can be solitary. You can be really high and then walk off stage and you’re on your own.

In those situations just getting your head to shut the fuck up can be tricky. After being so hyped on stage you need to wind down. The high, the feeling of getting a laugh is a hard drug to match and if you start going looking for it somewhere else you find it doesn’t exist. That can throw you out of sync.

That’s when I’d drink. It’s something I still haven’t got on top of to be honest. But now on tour I’ll drive to the next town after a show just to stop me drinking. I use the drive as a wind-down.

I read an article in the paper once about a comedian who didn’t have depression. I’ve had anxiety and I’ve had fear and I’ve confronted it. It started when I was on tour in Ireland and I had a panic attack brought on from being really tired. I was going ‘What the hell, am I having a heart attack here, what the fuck is this?’ I walked off stage. The next day people were walking up and talking to me and I was going into shock. It’s a frickIn’ scary thing if you don’t know what’s going on. I was having thoughts in my head that I just couldn’t bear they were that scary.

I was consumed by that fear for three or four years until one day I was in South Africa and I read this article that said the best way to confront fear is to ask for more of it. I couldn’t believe that could possibly be a solution. So I looked in the mirror and I go, ‘This is the only job you’ve got, no way are you backing down from this, in fact fucking bring it on, give me everything you’ve got’. I saw it as a person and I started to invite it on stage with me, like ‘You’re not going anywhere, you’re coming with me’. That was the thing that made it disappear. Now if I feel it coming on I start laughing, going, ‘Oh here you are, come with me’. It was a fight or flight thing, a human feeling.

Life’s hard for most people, not just funny people. The biggest laughs you get are when you’re being honest about your life.

It’s like a weight off your chest and that’s my whole act. I don’t pick on other people, I’m picking on me. I’m the idiot, I’m the fool, I’m the one who’s fucking up.

And when you say it, people go, ‘Me too, me too’. None of us are heroes. We’re all a sack of idiots.”

NAME: Damien Power

HOME: Brisbane

AGE: 35

“Growing up in Toowoomba, comedy never occurred to me as a possible profession. After doing uni I worked in IT. I started my own business writing software for kitchen design.

I know a surprising amount about kitchen benches.

I knew I wanted to perform so I started studying acting. In acting I found improv and through improv I found stand-up.

I realised I wanted people to applaud me. With every performer there’s a reason why they’re on stage and none of it is good. Often it’s because of low self-esteem. You’re compensating for something within.

A lot of comedians have issues with approval, rejection, acceptance, they just do. I think it’s very evident in comedy that you’re trying to get something from a performance that makes you feel accepted and praised. There’s stuff I didn’t get as a kid that I get through stand-up but I’ve learned that it’s not the whole answer. Whatever you’re seeking through an audience, or through drugs, or drinking to fill that void is not the answer. It’s about working on yourself so you don’t need to get it from an external source.

None of these issues is helped by being under immense pressure. Bombing in a gig is a real sense of rejection. And when you do well, it’s the opposite. It’s like a drug and it makes sense because you’re getting dopamine and all these things released. That’s the addiction. But these days it takes a lot more to get that feeling than when I started.

Being in bars every night doesn’t help either. Every time you finish a gig and it goes well you feel like you deserve a drink. You feel like you’ve just done this crazy, exhilarating thing. And if it goes badly, it can be the same. You’re like ‘Ugh, I’ll have a drink’.

I was mostly drinking straight whiskey but after being on antidepressants for a year and then coming off them I began to realise how much of a depressant alcohol was. So I cut right back. I’ve probably had about five drinks in the last year.

When you bring some of your own life to stage and you laugh at it there’s definitely a cathartic nature to that. From an audience perspective I think you’re getting better value for your ticket price because you’re going,

‘Oh wow, that’s profound and it’s funny’ or ‘That’s interesting and funny’. You walk away with other feelings.

What I’ve learned about stand-up is that you’ve got to know why you’re doing it. If you can understand what within yourself makes you want to do it, that’s going to be healthy for you and better for your career.”

NAME: Tom Gleeson

HOME: Romsey, Victoria

AGE: 42

“I was in a band and used to talk to the audience between songs. Often I’d give the songs sarcastic introductions so I had a feel for making an audience laugh.

At uni there was a stand-up competition and I ended up winning it. I was like, ‘Oh, maybe I’m good at this’. And then it dawned on me, ‘Maybe I’m better at this than being in a band’.

The thing I liked about comedy was that it was so immediate – the crowd either laughed or they didn’t. There was something so black and white about it that appealed to me.

During that first performance it felt like a white light had come up from my feet and shot out the top of my head. I couldn’t see momentarily. It was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. Afterwards I was buzzing. Quite often you see it at Open Mic nights where people are performing for the first time. They’re absolutely blotto off three beers because they’re on such a crazy high. It’s basic physiology: alcohol, plus adrenaline equals crazy times.

The way I cope with things now is I smooth it out. The really big moments for me aren’t a big deal and the really low moments aren’t a big deal either. I’m not going to walk off stage buzzing off my head on adrenaline because I’ve done a good gig. Whereas if I were to die on stage I wouldn’t want to kill myself. It’s kind of muscle memory from having done it so long.

I always enjoyed the performance aspect of comedy, jumping up and down on stage like a mad person and having everyone look at you. A friend of mine once told me that a lot of comedians feel like they’re not being heard. It might be a minority group that doesn’t have a voice or someone who comes from a working class family and feels like they’re ignored. In my case it was coming from a large family full of extroverts and not being able to get a word in.

In regards to mental health and comedy it’s a case of which comes first, the chicken or the egg? Does the profession create the condition or does the condition create the profession? The only thing I’ve had trouble with is drinking, which is pretty common. Everywhere I go there’s free booze. A couple of years ago I thought, ‘This is getting out of control – I’m just drinking all day everyday’. So I thought ‘That’s it, tomorrow I’m not drinking’ and I decided to count how many times in the day I was offered a drink. I ended up at something like 36 times. It’s a hazard of the game.

The biggest laughs I have are with people my age at a dinner party, where the laughter is laced with a certain sadness. Whenever you’re really laughing deep and hard and there’s tears in your eyes it’s not because someone observed that a sign was spelt incorrectly, it’s more about deep human truths. There’s a depth of emotion you get when you’re making

light of something that’s really upsetting. I like having those moments

in my show.”